Tomorrow we enter into the celebration of the Sacred Paschal Triduum, the climax of the liturgical year, commemorating the Last Supper, the Passion and Death, and the Resurrection of Our Lord, Jesus Christ. This year, Good Friday falls on March 25, thereby superceding the Solemnity of the Incarnation (the Annunciation), which is normally celebrated on that day, marking exactly nine months before Christmas.[1]

There exists, however, a custom that can be traced at least as far as Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240 AD), to make the Lord’s life on earth an exact number of years, even down to the day. Accordingly, March 25 became also the date of the Crucifixion. This tradition entered ancient martyrologies and was supported by homilists of the day. Subsequently, other customs developed. Calendars in the Middle Ages, for example, listed for March 25 the following events:

- The Creation of the World

- The Fall of Adam and Eve

- The Sacrifice of Isaac

- The Exodus of the Jews from Egypt

- The Incarnation

- The Crucifixion and Death of Jesus Christ

- The Last Judgment

Henceforth, it became an ancient ritual of the Roman Curia to start the Year on March 25, calling it the ‘Year of the Incarnation.’ This practice was afterwards adopted by many civil governments as well.[2] To this day, part of this tradition is preserved in the French town of Le Puy, which is known for celebrating a Jubilee when the solemnity of the Annunciation falls on Good Friday. The anniversary celebration dates back to 1065 in response to a calculation by a monk Bernhard who predicted the end of the world in 992 when the feast of the Annunciation coincided with Good Friday. The Jubilee of Le Puy last occurred in 2005 and will only take place again in 2157, after this week’s celebration, which will last until August 15, 2016.

Curiously, in the Byzantine rite, if Good Friday falls on March 25, the solemnity of the Incarnation is celebrated alongside the commemoration of the Lord’s Passion and Resurrection. This liturgical practice of the Eastern Church reminds us that these two mysteries of our faith, occurring closely to the vernal (spring) equinox in the northern hemisphere, are closely connected as they announce new life or a new creation. St. Ephrem, the fourth century Syriac writer, reflects on the new and everlasting springtime inaugurated by these concurrences of Nisan (the first month of the year in the Hebrew calendar which usually falls in March in the Gregorian calendar) as follows:

In the month of Nisan, when the seed sprouts in the warm air, the Sheaf sowed itself in the earth. Death reaped and swallowed it up in Sheol, but the medicine of life, hidden within, burst Sheol open. In Nisan, when lambs bleat in the meadow, the Paschal Lamb entered His Mother’s womb.[3]

Both mysteries, which recall the climax of the New Covenant, meet in the Mother of God. At the Annunciation, Mary gave her fiat—Let it be done to me—and conceived Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit. On Calvary, she repeats her fiat, thereby consenting to the sacrifice her Son and Redeemer offers for the sins of the world. Three days later, when he rises in glory from the tomb, Mary’s fiat surges into a jubilant Easter Alleluia. “How far the fiat uttered by Mary at the Annunciation had taken her!” marveled St. John Paul II in his 1988 Letter to Priests for Holy Thursday (§2).

The close union between Jesus Christ and Mary indicates that Christology and Mariology are inextricably interwoven. In God’s plan, as far as it is revealed to us, the Incarnation and Golgotha involved Mary’s cooperation. This truth inspired one of John Donne’s finest Divine Poems, written in 1608 when the Annunciation also coincided with Good Friday. Donne depicts Mary of Nazareth at the Annunciation “Reclus’d at home” and “Public at Golgotha,” pondering the consequences of her fiat for the conception of the Son of God, which ultimately led her to stand beneath his Cross:

At once a Son is promis’d her, He her to John;

Not fully a mother, She’s in Orbit,

At once receiver and the legacy.

All this, and all between, this day hath shown,

Th’abridgement of Christ’s story, which makes one

As in plain Maps, the furthest West is East

Of the Angel’s Ave and Consummatum est.

As we contemplate the meaning of discipleship during Holy Week, especially during the Triduum, we find our supreme model in the Blessed Virgin Mary. Her earthly journey, like ours, was marked by darkness and anguish. In spite of her unique election, she also had to tread the same valley of tears that all human persons have to endure. Experiences of grief and distress disclose her attitude of actively seeking communion with and participation in her Son’s suffering and Cross.[4] Above all, Mary’s attitude in her sorrow is archetypal for all humanity. It is in this context of assimilation and appropriation with Christ’s redemptive act that her strong union with Christ matures and is perfected in her own radical gift of self. St. John Paul II marveled at the unsurpassable degree of surrender achieved by the Mother of God:

How completely she “abandons herself to God without reserve,” offering the full assent of the intellect and the will to him whose “ways are inscrutable” (cf. Rom 11:33)! And how powerful, too, is the action of grace in her soul, how all-pervading is the influence of the Holy Spirit and of his light and power! (Redemptoris Mater, §18)

Hans Urs von Balthasar reminds us of the obvious: both Mary’s assent to the Incarnation and her “Yes” to her Son’s sacrifice on the Cross stem from her feminine, virginal, motherly, and bridal disposition towards God. She assumes the position of the New Eve, the helpmate of the New Adam.[6] Her cooperation beneath the Cross consists in her painful consent to the Father’s will. As at the Annunciation, so also on Golgotha, Mary speaks her fiat representatively for all of humanity.

The more seriously Christians take this letting-it-happen-in-me for themselves and their whole life of following Jesus, the more Marian is their baptismal faith. But because of that, they are also linked with Mary’s gesture of giving back her Son, from the beginning as far as the Cross, to the Father in the Holy Spirit. The Son has to do all the work that the Father wants him to do, and so into that work he fits Mary and all humanity.[7]

At the foot of the Cross, Mary embodies the Church as described by St Paul: “without spot or wrinkle . . . holy and without blemish” (cf. Eph 5:27; see also Lumen Gentium, §65). As we enter into the Triduum, we are invited to stand with Mary beneath the Cross uniting ourselves with her fiat as we continue on our earthly pilgrimage towards the eternal consummatum est.

![]()

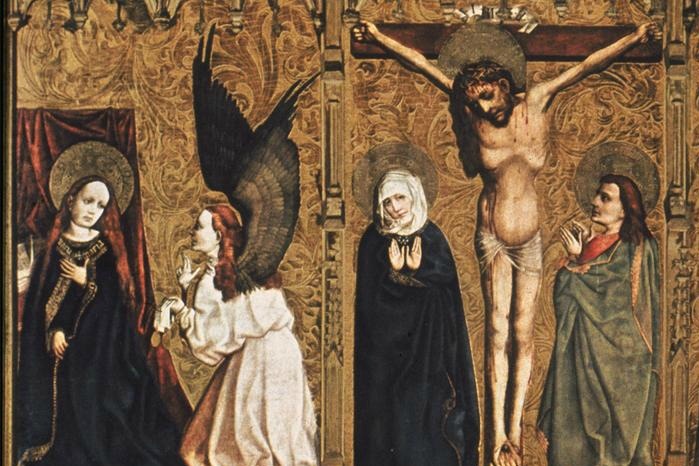

Featured Image: Tucher Altarpiece, detail: Annunciation and Crucifixion (c.1448); courtesy ARTstor Slide Gallery (University of California, San Diego)

[1] The Solemnity of the Annunciation will be celebrated this year on Monday, April 4.

[2] Cf. J.G. Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (New York, 1923), 632ff.

[3] St. Ephrem the Syrian, De Nativitate (Epiphania), trans. E. Beck, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, (Paris, 1903ff, Scriptores Syri, Louvain, 1959), 83.

[4] Cf. Joseph Kentenich, Sign of Light for the World: A Collection of Aphorisms (Constantia, S.A., 1980), 22.

[5] Cf. Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Drama, vol. 3: The Dramatis Personae: The Person in Christ, trans. Graham Harrison (Ignatius Press 1993), 369.

[6] Ibid., 372ff.