Throughout its long history, theology has certainly seemed more comfortable understanding itself through its claim to truth or goodness than to beauty.

It is not that the connection between theology and beauty has never been notarized. One simply has to recall the early Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, and the Dionysian tradition to realize that this is not true—even if beginning with Tertullian and proceeding through the iconoclasm controversy and on to the Reformation, faith in the Cross made it difficult to think of theology and beauty being anything other than bitter rivals, when it came to allure and existential pledge.

Of course, throughout the long histories of Catholic, Orthodox, and even Protestant theologies, there have been internal corrections. The Catholic theologian Matthias Scheeben might represent a correction within the late nineteenth-century form of Neo-Scholasticism, with its forged alliance between propositionalism and moralism. And, of course, in the Reform tradition no theologian showed a greater openness to beauty than Jonathan Edwards, without succumbing in the slightest to the emerging temptation to elevate beauty while essentially dethroning God.

Pace any number of narratives of decline, it has to be said that twentieth-century theology represents a high point when it comes to articulating the depth and extent of the linkages. Probably the two theologians who have most grandly articulated the connection are Hans Urs von Balthasar and Sergei Bulgakov, with the former proving to be the container and generous orchestrator of the very best reflection of the entire theological tradition. In his seven-volume The Glory of the Lord, the Swiss Catholic theologian includes for our consideration Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, the medieval theologians and, of course, Dante, but also opens us up the reflections of Bulgakov and Vladamir Soloviev and Karl Barth. In the case of the latter, Balthasar takes particular delight in the theologian who considered Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s music to be a form of divine and/or eschatological speech.

I will return to Balthasar in due course, but here I wish only to take advantage of the Mozart reference, which brings me back to my childhood in Ireland spent in public housing on the outskirts of Limerick City, whose damp misery was made famous by Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes. Amid the poverty, unemployment, huge families, problems with drink, unwanted pregnancies, and incarceration of males, there were enough examples of dignity in poverty to prevent hopelessness being inevitable. And some things had a kind of redeeming ridulousness: the very first person in the neighborhood to go to middle school was found worthy of the appellation of “professor.” But the most indelible memory, because this got played out week after week, was the weekend behavior of the twenty-something loner who lived next to us.

Let’s call him Mike. Mike was a construction worker who worked Tuesday to Friday, and religiously at 4:00pm on Friday he would begin the bender that would guarantee that he would be out of work on Monday. But also equally without fail, after the pubs closed on Saturday night he would play classical music, sometimes opera, most often Mozart. The music would compete with the trailing-off arguments as the participants grew tired or gradually realized that all aggression was the sign of their invisibility.

I suppose I did take in the sadness of it, and considered it a plaint against a life that was too much or too little. Yet I also regarded it as a small act of heroism, a declaration of hope that beauty could and maybe ultimately would win out over the ugliness which enveloped you and seeped into your soul. Mozart was divine speech, eschatological speech that spoke not only to but for one in one’s loneliness.

Although Mike wasn’t my only childhood inspiration, he was one of them, and it made me ask why was it that the Catholicism that saturated our public lives was not the vehicle of the promise of divine speech. Surely Catholicism could and should be able to mend lives, and mend them all the way down and across so that we might see a pattern to it all, the shine in things, to feel that one has been loved and can love, to sense that we have been given the impossible power to forgive others and ourselves.

Mike’s Mozart made the darkness luminous, and in the morning the cramped and jammed rooms of my house seemed less burdened and more open. In high school I began to learn that literature, and poetry in particular, could serve the same purpose. The poets came and went, Blake and Shelley, Yeats and Eliot, Mandelstam and Akhmatova, Milosc, Hӧlderlin, Rilke, Benn, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Char, and Nerruda and Paz, Hughes and Heaney. All of them provided a music of here, the music of what passes and ties together the scattering of time and the implosion of space.

They contained a signature of that divine music I shared vicariously with Mike next door, through the thin walls that separated and joined us together. It was hard not to recall the haunting line of Dylan Thomas when he spoke of the “walls wren bone.” Compacted in this image was the extremity of vulnerability, solidarity, and something like the mystery of vicariousness, and equally hard not to bring to mind the defaced one who on the Cross was and is and will forever be that form for me and for others of love broken and shared.

The appreciation of the grace-like features of literature never left me, even when it became clearer that literature presented the ever-present danger of becoming the carrier of the promise of redemption, and thereby enact a form of usurpation whereby the image replaced the Image, who alone can save us from the ugliness that leaks in and the ugliness we produce. Mike never knew how grateful I was for his Mozart, or how much healing as well as teaching occurred in the dark. He demonstrated more than all the books subsequently read and pondered that the beauty disclosed in any form of art provides more than temporary relief from ugliness and more than a cultural patina in which to gild a wounded life. Yet it was and is a sign of a sign and an image of an image.

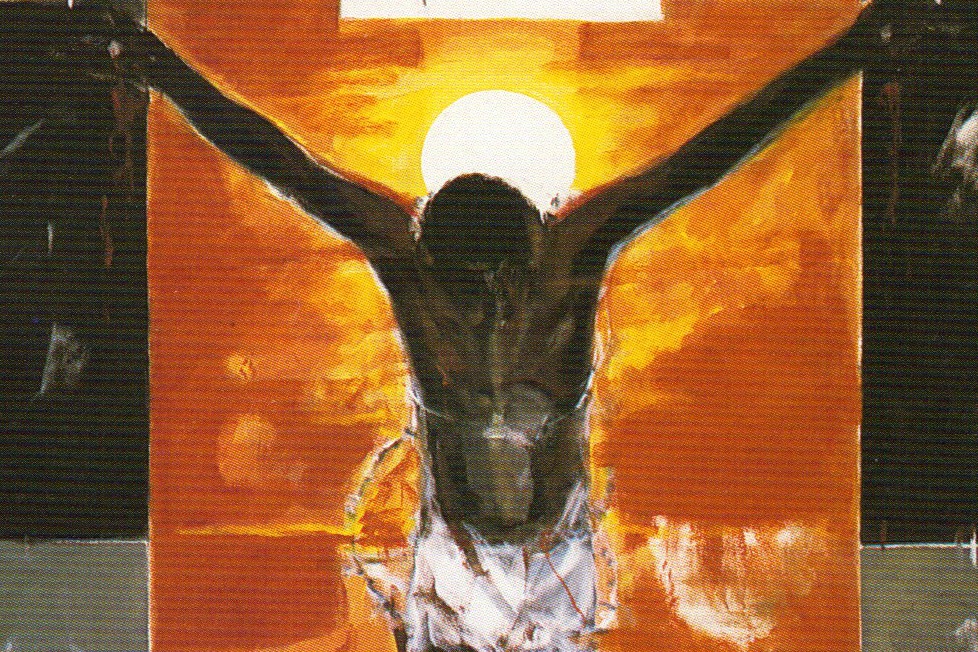

This leads me back to Mozart pondered by Barth and Balthasar, and their conviction that, at the very least in the christologically figured The Magic Flute, art and the beauty it renders is transitioning into witness of the glory of God in Christ who dies on the Cross and goes down to the utter inarticulacy of Sheol. For all his talk of theological aesthetics, Balthasar insists that the glory of the Cross is the point at which the ugliness of our individual and communal lives is transfigured.

Since Dostoyevsky, Russian religious thinkers have pondered the proposition that seemed to exceed them: Beauty will save the world. At the same time, whether in Soloviev, Bulgakov, or Solzenitzen—and its cross-over into the theology of Rowan Williams—it has not ceded to its default secular interpretation. The beauty that saves comes in the night and may not be recognized when it comes, because it has not forgotten the traces of the ugliness overcome. The glory of the Cross requires a cleansing of perception that only love and grace provide. And if it does that, it also enables us to see that all forms of beauty are ambassadors of divine glory and analogies of that truly eschatological gaiety that transfigures all dread.

![]()

Editorial note: A version of this article was published in Yale Divinity School's Reflections magazine in 2015.

Featured Image: Ruiz Anglada, Cristo Negro, detail (1995); CC BY-SA 3.0.