It is common knowledge that the homilies offered in many Catholic parishes (how can one say this charitably?) often have a lot of room for improvement. The quality of Catholic homilies, of course, varies widely according to the specific parish and priest involved. I have actually heard some of the best sermons of my life in Catholic Masses. But I have also heard plenty of lousy homilies too. So, if the common view on Catholic homilies has at least some basis in fact, it can only strengthen the Church if those responsible for offering homilies consider ways to improve them.

As a sociologist of religion who has studied and reflected upon church meetings and sermons for many years, I suggest the following, which I think can significantly improve the quality of many Catholic homilies. One of the main reasons that homilies and sermons are bad is because they are unfocused; they try to make too many points at once. If so, that problem is readily fixable. How?

Before addressing this problem, let us remember as background that success here is not defined by the homily itself, but about how hearers are formed by homilies—their practical effectiveness in communicating truth. It does not matter that a homily is amusing or elegant or theologically astute or anything else in and of itself. Preaching is not ultimately about the homily or the person giving it. It is rather about effective communication by which the Church forms God’s people in truthful and good ways. Ideally, the homily and homilist should become somewhat transparent, so that the message of the homily stands out and impresses itself upon the hearers in a way that forms them well.

That said, how can the problem of unfocused homilies be fixed? The answer, I think, is to focus the homily on one and only one really important point. Way too many sermons (both Catholic and Protestant) have, as I have said, little focus. They often ramble about, saying various and sundry things that are more or less true and may be quite admirable. But, having listened for fifteen, thirty, or forty-five minutes, those in the pew end up walking away with little clue about what the speaker actually said. Much is spoken with minimal impact. Everything we know about human cognition and learning tells us that both operate with severe limits, even for smart people. People can only absorb so much information and engage so many challenges at one time.

Every homilist therefore needs to get perfectly clear upfront regarding what exactly the people who hear it should walk away believing, thinking, knowing, or doing as a result. In what specific way should the listeners be different as a result of hearing the homily? If this homily were to succeed marvelously, what specifically would that success look like? How would its hearers live differently because they heard it? Then, every possible idea that does not clearly help to achieve that one purpose, that single focus, that clear vision of success, should go. Just cut it out.

This maxim does not mean that the homily consists of repeating the same thing over and over again. Talking about one important point is not the same as simply repeating oneself. In fact, it is usually necessary in any good presentation to craft a talk that leads up to, makes, circles around, and reinforces the same one important point in a variety of ways—perhaps including personal stories, scriptural reflections, doctrinal teaching, real-life illustrations, and so on. But never should any of that be included in a homily if it does not clearly contribute to communicating the one clear important point of focus.

In short, always focus everything—every story, argument, reference, illustration, and exhortation— on the one point of the homily. Everything else is expendable, because it gets in the way. If something else is still really important but unrelated to this homily, it can be said later, in some other homily focused on that valuable idea. Remember: one point at a time.

So, when the homilist sits down to work on the homily, the mantra should be: “Less is more. Focus. Make only one important point. Less is more.” If such a homilist can get their listeners to really hear, absorb, and work on living into or out of one important point per week, adding to fifty-two distinct, significant homily points per year, that would be a major success; compared to what usually happens, which is too many unfocused ideas not well retained or acted upon by anyone. And fifty-two really important points accumulated and reinforced over many years will surely help to form God’s people in good ways.

I hope this column itself illustrates my point. So, in keeping with this approach, cramming too many ideas into one homily is a bad idea. It backfires. The more homilies demand their listeners to hear, the less they actually get. We know that. So, Catholic homilies may be dramatically improved by implementing a few changes, the first of which is to always focus on one key point and to make sure everything that gets said in the homily states, clarifies, develops, and reinforces that one important point.

![]()

Editors’ Note: This article originally appeared in Church Life: A Journal for the New Evangelization, volume 1, issue 2.

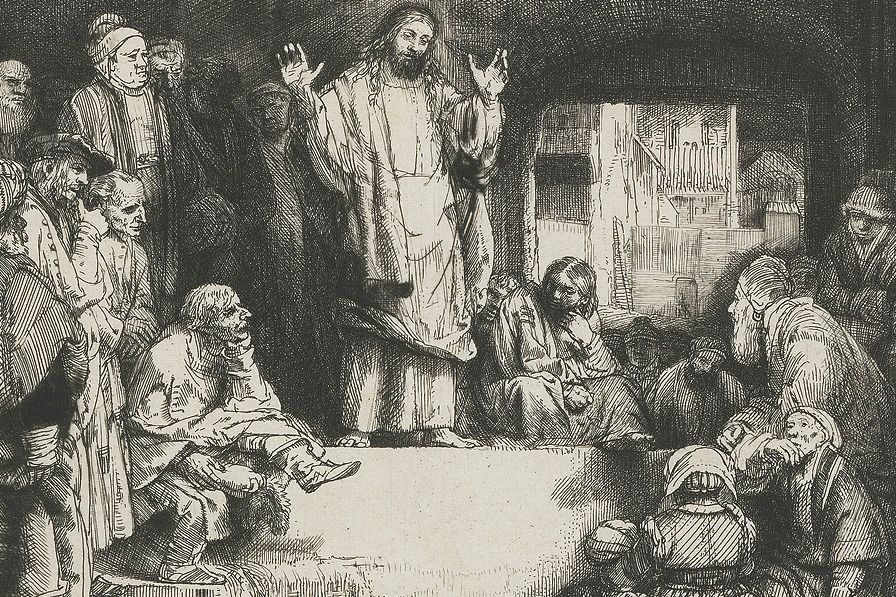

Featured Image: Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Preaching (La Petite Tombe), detail (ca. 1652); courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.