Every saint is idiosyncratic. On the face of it, this seems so self-evident that we might wonder why it even needs to be said. Of course, St. Ignatius of Antioch is different from St. Ignatius of Loyola. Obviously, St. Teresa of Ávila is not St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Even when saints bear the names of the holy men and women who preceded them, they are never carbon copies of their namesakes. Each saint’s radical particularity deserves special attention, because it tells us something vastly important about the personal character of every individual’s pathway to sanctity. It should not surprise us that God calls everyone to embrace the vocation of sainthood, because each person is destined for union with God—an everlasting intimacy that the Holy Spirit enacts in us through the process of sanctification. Sainthood’s universality entails its idiosyncrasy. If God wishes for all of us to be saints, there must be as many ways of being a saint as there are people whom God transforms into them. Thomas Merton, famed twentieth-century Trappist contemplative and social activist, expresses it this way:

Those who fulfill their vocation to sanctity—or who are fulfilling it—are by that very fact unaccountable. They do not fit into categories. If you use a category in speaking of them you have to qualify your statement at once, as if they also belonged to some completely different category. In actual fact, they are in no category, they are peculiarly themselves, hence, they are not considered worthy of great love and respect in the eyes of men because their individuality is a sign that they are greatly loved by God and that he alone knows his secret, which is too precious to be revealed to men. What we venerate in the saints, beyond and above all that we know is this secret; the mystery of an innocence and of an identity perfectly hidden in God.[1]

It would be a mistake for us to think that our call to sanctity implies the elimination of our individuality so that we might replicate the saints of the past. Merton explains that becoming a saint requires being entirely one’s self—the self that is “perfectly hidden in God.” How do we become ourselves, discovering the “secret” identity that God’s love births within us? The Holy Spirit sanctifies the individual by giving her insight into her true essence. This discernment is a lifelong process, so that every moment and event that contributes to each individual’s peculiar history can be used for the sake of more deeply penetrating the mystery of one’s selfhood in God.

Every saint has a past that includes sins and failings that can be catalysts for conversion if they are confronted with the courage and strength that God’s grace provides. St. Augustine’s celebrated Confessions recounts exactly this kind of Spirit-motivated self-discovery that liberated Augustine to willingly become his true self in light of God’s desires for him. Augustine’s story was different from anyone else’s, because his path to sanctity involved his straightforward telling of his distinctive life story in order to understand it and reshape it alongside other Christian believers who were pointing him to Christ. Likewise, every saint comes to grips with her unique life experiences by locating her center in Christ with the support of Christ’s Body, the Church.

Our inability to “categorize” or “account for” the saints because of each one’s individuality means that the Christian community does not rank saintly differences. Therefore, we do not say that this saint is better than that saint, because the first is famous and the second is obscure. Nor do we say that one saint’s route to holiness is superior to another’s because the latter took longer to arrive at her true vocation. Joined together by the Holy Spirit with the common goal of becoming one with the triune God, the members of Christ’s Body witness to the Christ who dissolves all such comparisons. Ultimately, there is one saintly life form that all saints model themselves after in crucially different ways: Christ. As Merton explains, “this imitation consists in being and acting in the same relation to Jesus as Jesus to the Father.”[2] And, what does Jesus do? To answer this, Merton directs us to John’s Gospel where we find Jesus attentively listening to the Father to ascertain who the Father wants him to be so that he can live his life accordingly. The twentieth-century Swiss Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar agrees with Merton when he writes: “They [the saints] never at any moment leave their center in Christ. They give themselves to their work in the world, while ‘praying at all times’ [like Christ did] and ‘doing all to the glory of God’ [like Christ did].”[3] The universal call to sanctity comes from Jesus, and the Holy Spirit aids individuals to respond to that call by personally following the incomparable Savior.

Saintly imitations of Christ are essentially dissimilar, because God has created individuals who are each freely emulating the mystery of the incarnate Son within a special life story that reveals Christ’s love in a singular way. All persons are united along their various roads to holiness, because everyone has been recreated in Christ to follow his example of listening to the Father speak their identities afresh in the grace of the Spirit. We cannot refuse to set out on our saintly journeys because we are unable to become like this or that saint that we have been revering from afar. We need not traverse any other road than the one that we are on presently. Our Christ-like awareness of God’s voice speaking to us in the midst of our everyday triumphs and failures will lead us to claim our unrepeatable identity that God alone can give to us.

![]()

[1] Thomas Merton, Thoughts in Solitude (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998), 70.

[2] Ibid, 107.

[3] Hans Urs von Balthasar, “Theology and Sanctity,” in Explorations in Theology I (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1989), 195.

Editors’ Note: This article originally appeared in Church Life: A Journal for the New Evangelization, volume 2, issue 4.

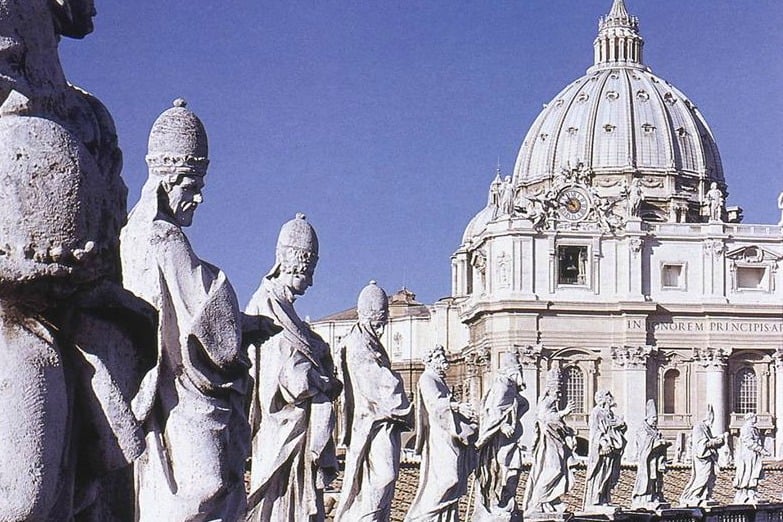

Featured Photo: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saints of the Colonnade (1656-67); St. Peter’s Basilica (Vatican); courtesy ARTstor Slide Gallery (University of California, San Diego).