All you who are thirsty,

come to the water!

You who have no money,

come, receive grain and eat;

Come, without paying and without cost,

drink wine and milk!

Why spend your money for what is not bread;

your wages for what fails to satisfy?

Heed me, and you shall eat well,

you shall delight in rich fare.

Come to me heedfully,

listen, that you may have life.

I will renew with you the everlasting covenant,

the benefits assured to David. (Is 55:1–3)

We are all thirsty. We are all hungry. We are all poor. However, if we heed the Lord we are given water and wine, milk and grain. Indeed, we delight in rich fare; it is the banquet of our God. The prophet’s words to those dispersed to participate in God’s plan for the restoration of Israel need not be locked in a purely historical framing. The prophet extends the promises made to David to the whole of God’s people; a renewed promise to all who are thirsty, to all who are poor—that is, to us. If we can perceive, by means of the Mystery, the everlasting covenant as sacred history we find that, throughout all of time, “God is the one Who gives.”[1]

Surely, God is the one Who gives at creation, establishing all things out of no calculated motive—but rather out of a nearly irrational motivation—Love. Certainly, God is the one Who gives in establishing the covenant with Abraham, in liberating God’s people from captivity in Egypt, in restoring this people to new life even after they had abandoned not only the gifts given, but even the Giver. The words of the prophet point us to the Giver who acts—at least according to the standards of those who find it troubling to give in such an absolute way—irrationally, that is, miraculously.

Assuredly, God is the one Who gives by the Incarnation. God becoming human—for no reason other than to restore all of God’s people—constitutes a restorative process that begins with the Annunciation and culminates on Calvary. God is the one Who gives when Christ descends into hell so that all of those who have waited in faith for the restoration promised might accept such a gift. Inconceivably, God is the one Who gives in overcoming, vanquishing, destroying death and restoring life in the Resurrection.

What an abundant outpouring of gifts the long view of sacred history makes present. As Sofia Cavalletti explains so well, “God’s gifts are not rationed according to our minimal necessities; rather, they are poured out abundantly, in accordance with the giver’s abundant love.”[2] This is consistently God’s method, and we who receive need to real-ize—to make real—this history of gifts by examining the Mystery of Love: “Because the gift is meant to establish a relationship, it is of uppermost importance that we pause to ponder the gift.”[3]

Where do we pause more completely than in our prayer, and in our celebration? The liturgy which makes present the long view of sacred history in the singularly constant moment of God’s gift—at once historical and cosmic—allows us all to see absolutely that, as we thirst, as we hunger, we who are abundantly poor are incredibly satisfied. Our satisfaction now points forward to the fullness of gift to come when Christ will come again; when, once again, God will be the one Who gives.

Heeding the Lord in “wonder and amazement”[4] allows for our response to the one Who gives, which is nothing more, or less, than saying “yes” to the life that has been won for us, to the God who has been given us.

![]()

Christopher Gattis is entering his second year of the Master of Divinity program at the University of Notre Dame.

Editors’ Note: This text was delivered as a homily at Morning Prayer during the Center for Liturgy Symposium, Liturgy and the New Evangelization. We are grateful for the author’s permission to publish it here.

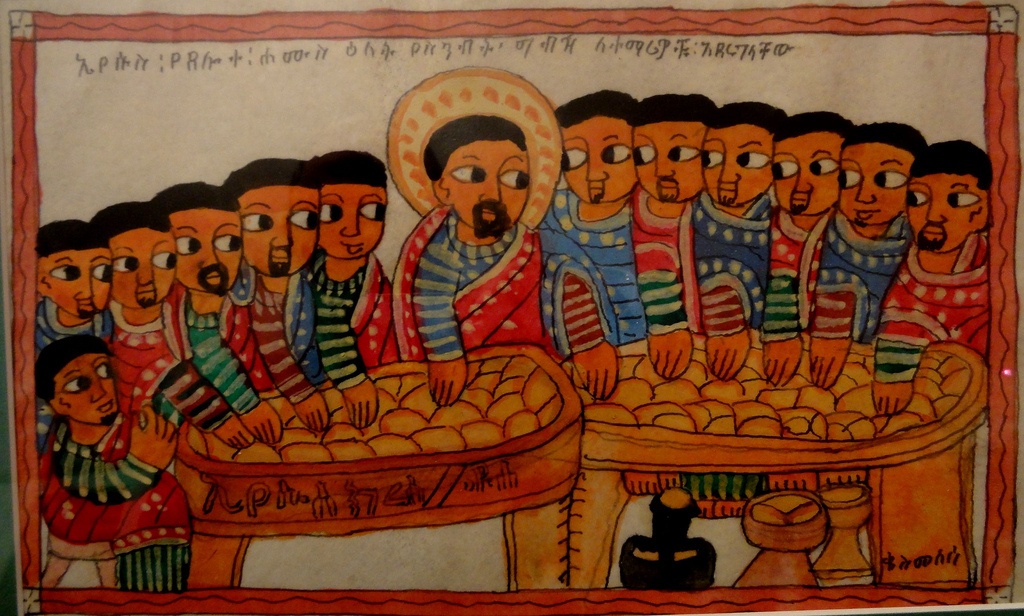

Featured Image: Jim Forest; CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0.

[1] Sofia Cavalletti, The Religious Potential of the Child: 6 to 12 Years, trans. A. Perry and R. Rojcewicz (Chicago: Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Publications, 2002), 28.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 30.

[4] Ibid.