A Triptych of Short Fiction, Sacred Art, and Modern Poetry

This is an essay about vision and blindness, about seeing and the failure to see, about wholes and fragments, sickness and healing, light and darkness, about nativity and the rebirth to eternal youth, about a mode of beauty that does not and cannot exclude ugliness, the nocturnal, suffering, and death but rather fundamentally transfigures it. It is about forms of art, yes, but also—and far more importantly—about forms of life, and the vivifying, even healing shapes these can and ought take for Christian believers.

Early on in T. S. Eliot’s pageant play The Rock, which narrates the rebuilding of a Church, the Chorus laments: “Where is the Life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?”[1] Here the depth dimension of genuine wisdom and mystery has been traded for bits of data. Similarly, the modern person has in a certain sense become blind, unreceptive to theological and even philosophical language, unable to discern the immediacy of God in the world, as the metaphysical and the transcendent have given way to the unfortunate hegemony of scientific, psychological, or purely technical reason. In our age, beauty and—not coincidently, religion, too—have been quarantined to the private, subjective sphere, where adherence or non-adherence, seeing or refusing to see, becomes simply a matter of personal preference or taste. We are a people who have by and large forgotten how to see, people for whom the language of beauty is no longer legible, and this contraction of the theological imagination is no small or indifferent matter. To have forgotten how to see is to foreclose an infinite horizon of possibilities, to fail to be attuned to the capacity for in-breaking mystery in the Church and in the world, to constrict our true selves, and, in short, to be in need of healing. Beauty, though, has a mysterious capacity to heal, to reanimate, to renew and to restore the theological imagination, and to be a salve to thoroughly desiccated modern sensibilities where what gets valued is the pragmatic, the empirical, the calculable, the merely scientific.

To have forgotten how to see is to foreclose an infinite horizon of possibilities.

Using lines from the choruses of Eliot’s The Rock as a way of “keeping time” and organizing these comments, I will move rather expediently through five points which invite consideration of glimpses of the healing capacities of the beautiful in a kind of triptych of short fiction, sacred art, and modern poetry, and, as condition of the possibility for all the rest, a very robust Christology. Here Hans Urs von Balthasar, known both for his incredible cultural virtuosity as well as for what is perhaps the canonical version of contemporary theological aesthetics which attempts to reinstate beauty as a viable category both for theology and for Christian living, is my guide both formally and materially. For him, it is Christ who, as the full expression of the infinite in finitude, is “God’s greatest work of art” and functions absolutely generatively for all other beautiful things.[2] Indeed, this essay might be considered aspirational to and a microcosm of Balthasar’s own method, which welcomes a pastiche of aesthetic forms as genuine sources for the theological conversation, fragments that share mysteriously in the beauty of God.

I will begin with Raymond Carver’s short fiction piece “Cathedral,” a story of a thoroughly irreligious man who has a fragile and unlikely moment of religious transcendence when a blind man comes to visit, and they stay up too late watching television. We will then make an examination of Matthias Grünewald’s magisterial Isenheim Altarpiece as a tangible and very literal illustration of the collision of healing and beauty, and conclude by turning more decisively to the sublimely poetic language of Eliot. Again, the base that undergirds this triptych is a Christologically governed theological aesthetics borrowed from Balthasar. I argue alongside him that much is at stake both theologically and spiritually in the recovery of beauty, as we reflect upon what it might mean to infer from these forms of art something about the forms of life to which Christians ought accord themselves.

“Our little light, that is dappled with shadow”:

Blindness & Healing Vision in Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral”

In his unapologetically irreverent and occasionally crass short story “Cathedral,” Raymond Carver relates what is at the plot level, quite simple. It is not difficult to tell in fairly short order: immediately after the death of his wife a blind man named Robert comes to visit an old friend, an unnamed woman, who had once spent a summer employed to read aloud to him. Over the years, the blind man and the woman had kept in touch over the years by the exchange of lengthy cassette tapes sent through the mail rather than letters. The story is told from the straight-shooting perspective of the woman’s rather aggressively obstinate husband, who is altogether displeased by the blind man’s coming. When Robert arrives, it is all incredibly awkward, just a few inelegant stabs at conversation that amplify and draw attention painfully both to the visitor’s disability and to the husband’s inability to see anything else about him. They smoke, they eat dinner, they drink, they talk, then when all these pained pleasantries become exhausted, the husband turns on the television, perhaps the height of rudeness when entertaining a guest who is unable to see. It gets late, and Robert and the husband are left attending the TV: all that is on television is a program on medieval cathedrals. In a rare moment of thoughtfulness, it dawns upon the husband that the blind man has never been able to see or to experience what a cathedral is. He says to the blind man:

“Something has occurred to me. Do you have any idea what a cathedral is? What they look like, that is? Do you follow me? If somebody says cathedral to you, do you have any notion what they’re talking about? Do you know the difference between that and a Baptist church, say?”[3]

Now, the husband’s capacity for spiritual vision has been so truncated, his forms of expression so limited, that to witness his epically unsuccessful attempts to describe what is being pictured on the screen to Robert is absolutely cringe-worthy for the reader to witness. Carver continues:

“You’ll have to forgive me,” I said. “But I can’t tell you what a cathedral looks like. It just isn’t in me to do it. I can’t do any more than I’ve done.”

The blind man sat very still, his head down, as he listened to me.

I said, “The truth is, cathedrals don’t mean anything special to me. Nothing. Cathedrals. They’re something to look at on late-night TV. That’s all they are.”[4]

What happens next is, however, a rapturous moment where a delicate moment of beauty seeds itself transformatively in the heart of the husband. The blind man suggests the idea that they might draw a picture of a cathedral together. The husband collects a pen and some heavy brown paper, and then, sitting side by side on the floor by the coffee table, they begin to draw together, the blind man’s hand clasped on top of the husband’s, as he draws, at first clumsily and tentatively, and then with growing earnestness that expands into near-mystical transport. Carver goes on, from the perspective of the husband:

I put in windows with arches. I drew flying buttresses. I hung great doors. I couldn’t stop. The TV station went off the air. I put down the pen and closed and opened my fingers. The blind man felt around over the paper. He moved the tips of his fingers over the paper, all over what I had drawn, and he nodded.

“Doing fine,” the blind man said.

I took up the pen again, and he found my hand. I kept at it. I’m no artist. But I kept drawing just the same.

My wife opened up her eyes and gazed at us. She sat up on the sofa, her robe hanging open. She said, “What are you doing? Tell me, I want to know.”

I didn’t answer her.

The blind man said, “We’re drawing a cathedral. Me and him are working on it. Press hard,” he said to me. “That’s right. That’s good,” he said. “Sure. You got it, bub, I can tell. You didn’t think you could. But you can, can’t you? You’re cooking with gas now. You know what I’m saying? We’re going to really have us something here in a minute. How’s the old arm?” he said. “Put some people in there now. What’s a cathedral without people?”

My wife said, “What’s going on? Robert, what are you doing? What’s going on?”

“It’s all right,” he said to her. “Close your eyes now,” the blind man said to me.

I did it. I closed them just like he said.

“Are they closed?” he said. “Don’t fudge.”

“They’re closed,” I said.

“Keep them that way,” he said. He said, “Don’t stop now. Draw.”

So we kept on with it. His fingers rode my fingers as my hand went over the paper. It was like nothing else in my life up to now.

Then he said, “I think that’s it. I think you got it,” he said. “Take a look. What do you think?”

But I had my eyes closed. I thought I’d keep them that way for a little longer. I thought it was something I ought to do.

“Well?” he said. “Are you looking?”

My eyes were still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything.

“It’s really something,” I said.[5]

This is where the story ends.

In quite a real sense, the husband’s spiritual vision is restored, healed, as it were, and he sees rightly without even opening his eyes, through this near mystical experience of connection, as the blind man and the sighted man move their fingers over the bas relief of a pen drawing of a cathedral on the back of a brown paper grocery bag. The symbol of hope and rebirth in this drawn cathedral—something that blind and sighted have built together in a kind of tenuous community—attends an absolute sea-change from the skeptical, callous, sarcastic character we first meet in the opening lines of the story. This shock of a simple encounter actually does something, actually effects a change in the spiritual health of the sighted man.

Of course it is the blind man who is in the first instance the agent of vision, the character who can in a sense see beyond what the other characters can see—continuing a long and venerable literary trope, of course, including the luminously clairvoyant but physically blind Tieresius in Greek mythology, the blind beggar attending Emma’s death in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, even the way blindness functions symbolically in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? as a recapitulation of Homer’s Odyssey, as well as many other instances, both literary and cinematic. In various ways, these examples pose the question of what it might mean actually to see. What or, more fitting here, who is the beautiful, and how does our attention to the beautiful heal our human desire?

“O Light Invisible, we glorify Thee!”:

Rehabilitating Beauty in Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Theological Aesthetics

"Rehabilitating” beauty in the title of this sub-section is meant in a double sense, to indulge a bit of a grammatical excursus: in the first sense, the verb functions gerundively, as a noun. It names Balthasar’s chosen task. That is, his work is a conscious recovery and restoration of beauty—which has been relegated to the merely subjective—back to the “main artery which it has abandoned.”[6] Balthasar begins his sixteen-volume trilogy by asserting, perhaps counter-intuitively, that “Beauty is the word that shall be our first.”[7] The story of the evacuation of beauty from Western sensibilities that Balthasar is telling is a sad one, in which something vitally important—beauty as an objective entity, a transcendental unified with goodness and truth—has gotten lost and requires full rehabilitation. Historical theological and philosophical reflection, exemplified perhaps most arrestingly in Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, seems to indicate that between the religious and the beautiful, a choice must be made, and it is nearly always the latter that is disparaged.

The second meaning of our sub-title “rehabilitating beauty” is participial, acting as an adjective. It describes the effects of beauty as a restoring force, a power that calls human beings back to true vision and, effectively, to our own true selves. For Balthasar, the stakes are high. To disengage from beauty denatures the good and the true. He writes:

Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance. We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past—whether he admits it or not—can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.[8]

These, of course, are very strong claims. But for Balthasar the loss of beauty from the modern sensibility is a serious business insofar as the good and the true lose their self-evidence and can no longer compel us with an inner necessity.

In his foreword to the first volume of The Glory of the Lord, Balthasar indicates that beauty is objectively located at the complementary junction of species and lumen, or “form” and “splendor,” a distinction with great precedence in medieval aesthetics rooted in Christian Neoplatonism. For Balthasar, the complementary relationship between “form,” that is, the shape of something, and “splendor,” or its interior luminosity, is evident insofar as in the perception of beauty “we are confronted simultaneously with both the figure and that which shines forth from the figure, making it into a worthy, a love-worthy thing.”[9] This luminosity emerges from within the interior of the form. The appearance of form has currency as something beautiful because it is the reflection of that which is, an expression of reality itself, and “this manifestation and bestowal reveal themselves to us as being something infinitely and inexhaustibility valuable and fascinating.”[10] The form, in short, is a participation in the totality of being, in infinitude itself. It should come as no surprise, then, that his theological aesthetics is governed thoroughly by the singular, perfectly un-foreseeable instance of the infinite expressed in the finite, namely Jesus Christ, to whom we shall now turn.

“The light that fractures through unquiet water”:

Beauty in/as the (Christological) Fragment

The concept of beauty has a long history in the Christian theological tradition of being connected to the Persons of the Trinity: whether to the Father as Creator, the Son as Christ the Word made Flesh, and/or the Spirit as sanctifier of matter. Here I will privilege the Christological, though with the qualification that in Balthasar’s thought Christology and Trinity are perfectly indivisible, so if Christological, then Trinitarian. It may be a temptation to assume that a theologian who intends to reclaim the concept of beauty for theological discourse may tend methodologically towards abstractions. For Balthasar, however, it is Christ—the absolutely singular and perfectly concrete instance of the infinite expressed in the finite in a genuine flesh-taking—who is the “Ur-form” of beauty.[11] Balthasar understands the “event” of beauty essentially, as the German title of one of his books suggests, as Das Ganze im Fragment, “the whole in the fragment.” Because of Christ, other finite forms—whether of nature, art, language, poetry, philosophy, and, somewhat differently, the sacraments—are capacitated to participate in some measure in this mystery, where the supernatural acts as a kind of leavening agent all throughout the “natural,” and it becomes an impossibility to demarcate these into two hermetically sealed spheres.[12]

Because of the mysteries of creation and Incarnation that invigorate the forms of the physical world with divine presence, “we can encounter the deep mystery of God nowhere else but in the context of the world it informs.”[13] It is through these concrete, visible fragments of beauty that the “the lightning-bolt of eternal beauty [can] flash.”[14] This encounter—analogous, perhaps, to being confronted with an especially masterful painting—is characterized by the simultaneous moments of beholding and of being enraptured, both of which are conditions of the possibility for the other. In the perception of any beautiful form (recalling perhaps, Carver’s story) there is always an element of surprise or shock, a sort of rupture of being taken aback. In Balthasar’s words, “the ‘shock’ of the Word becoming flesh—an event so revolutionary that it surpasses all possible anticipation” is an “extravagance” that in its singularity of human and divine together, is the form of forms.[15] The modern person thus needs to be confronted with the phenomenon of Christ and, “therein, learn to see again—which is to say, to experience the unclassifiable, total otherness of Christ as the outshining of God’s sublimity and glory.”[16]

The salvific efficacy of the Christological “whole in the fragment,” however, is not just that wholeness shines perspicuously through the Incarnation, but also includes, of course, a shattering and fragmentation of a different kind in the Crucifixion: indeed, for Balthasar “the most sublime of beauties [is] a beauty crowned with thorns and crucified.”[17] Here Eliot’s The Rock goes on, too, underscoring to us in another way the cruciform nature of the form of true beauty.

Now you shall see the Temple completed

After much striving, after many obstacles;

For the work of creation is never without travail;

The formed stone, the visible crucifix,

The dressed altar, the lifting light,

Light

Light

The visible reminder of Invisible Light.[18]

We are given to understand, then, that the possibilities for what counts as the beautiful do not exclude, but rather transfigure tragedy, ambiguity, fragility, ugliness, and death.

“That darkness reminds us of light”: A Johannine Theologia Crucis and the Isenheim Altarpiece (1510–15)

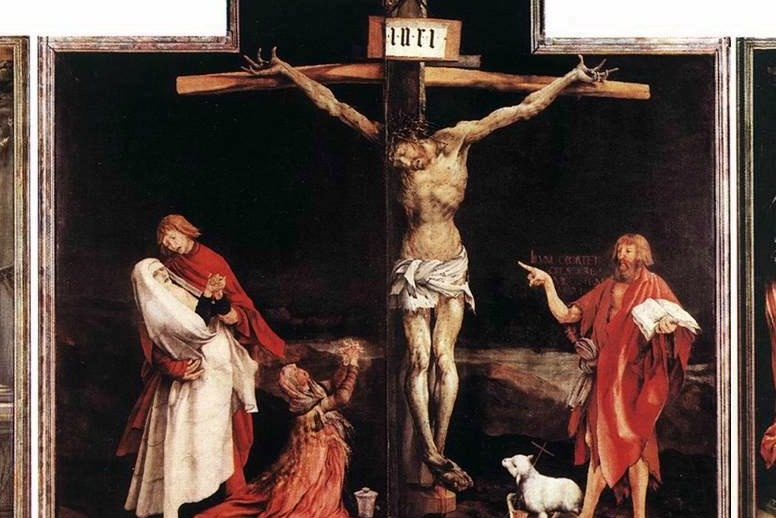

For Balthasar, whose theological imagination is formed most decisively by the Johannine corpus, especially the Gospel of John and the book of Revelation, it is altogether imprudent to venture to speak of the beauty of God apart from the form actually expressed in salvation history.[19] This is the form of cruciform love, which is all self-gift, and in the Gospel of John in particular, the Crucifixion is read as the doxological moment of the text, at which the glory of God’s love shines forth brightly in spite of—or perhaps because of—the twisted “formlessness” of the figure of Christ on the Cross.[20] To illustrate this point more concretely, I have chosen a well-known example of Renaissance art for our consideration: Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, an enormous composite polyptych completed between 1510–1515, which unfolds into three levels.

Isenheim Altarpiece, final open position with sculpture by Nikolaus Hagenauer

Isenheim Altarpiece, final open position with sculpture by Nikolaus Hagenauer

I chose this particular work of art for several reasons. One is that it seems to me to be a material enactment of this Johannine tendency to depict the outer limits of both profound suffering and supernatural glory in the very same installation. Secondly, this large altarpiece can be thought to be a complex study in wholes and fragments. Interestingly, besides the fact that it depicts a multiplicity of scenes in plural media, but ought be regarded as a unity, the actual piece itself has known material fragmentation, having been dismantled and stored in the Colmar library during the iconoclastic fervor of the late 1700s.

Isenheim Altarpiece, closed position

Isenheim Altarpiece, closed position

When in the closed position, it depicts the famously gory crucifixion scene flanked by two saints of healing: St. Sebastian, who was thought to have the power to protect against plague and epidemic disease, and St. Anthony, whose curative ability is attested to in Athanasius’ well-known hagiography, The Life of Antony. The lower panel shows—in stark and nearly unbearable detail—the body of Jesus having been removed from the Cross, truly dead with the dead. In the middle position, there are scenes of newness, rebirth, and hope for the amelioration of suffering: the Annunciation, an angelic concert, the Madonna and Child, and, finally, one of the most striking and gorgeous scenes of the Resurrection ever painted. In the third, open position, there is an older wooden sculpture gilded with gold (by Nikolaus Hagenauer) which includes St. Augustine, St. Anthony, and St. Jerome, along with Christ seated with the twelve Apostles in the lower, supporting base panel. On either side of the sculpture are fantastical scenes from the life of St. Anthony, the first of his meeting with Paul the Hermit, and the second a rather gruesome scene of his being tempted by fierce demons.

The third reason I selected this example is that it explicitly connects beauty and healing insofar as the original physical context in which the piece was housed is the chapel monastery of the Antonite community, which was a hospital order. Most of the patients there suffered from ergotism, an infectious skin disease caused by ingesting poisoned rye that also went under the banner of “St. Anthony’s fire.” The piteous figure of the demon in the lower left likely depicts the ravages of this particular disease on the human body, including skin discoloration, boils, a swollen stomach, an amputated left arm, and, obviously great and isolating pain.[21] Poignantly, the scrap of paper on the lower left is inscribed with a Latin inscription borrowed from Athanasius’ Life that laments, “Where were you, good Jesus, where were you? Why were you not there to heal my wounds?”[22]

What might it mean, or have meant, to see this piece, to behold it as a unified work of art yet one composed of many parts, with content this seemingly incongruent? How might it be interpreted, for those with eyes to see? What would it have meant for the original viewers under monastic medical care, that this piece was in a sense both static and dynamic, that though at any given moment the beholder could see only one aspect, there was also always already the possibility for unfolding progression and promise, because now cruciform beauty points to hope?[23]

Consider first the exterior or closed view of the piece, which depicts a devastating Crucifixion scene, especially in the splayed fingers of Jesus, the lacerated, discolored body, the crudely twisted feet. On his right, Jesus is mourned by John, the beloved disciple, Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdelene. On his left, Jesus is anachronistically heralded by John the Baptist (who, according to the Gospels, had of course already died by the time of Jesus’ Crucifixion), and attended by the Lamb as though slain from the Book of Revelation—bleeding, in an abundance of liturgical imagery, from its torn side into a Eucharistic chalice.

The inclusion of the slain Lamb here is a latent promise of sacramental healing that gestures towards the more hope-filled images directly underneath in the second set of panels. Below the main panel in a lower register is the depiction of the Entombment, which, like the Crucifixion above it, certainly does not shrink from depicting the authentic disfigurements of death. Neither can be identified unambiguously as beautiful either in terms of actual content, pleasingness to the eye, or even intuitive proportionality, if we compare, for instance, the size of Mary Magdelene to that of John the Baptist. If we recall from Balthasar the inversion of beauty that can now include the cruciform, however, it is easier to see how these images might, in a sense, effect healing of a sort.

In the first instance, there is a kind of solidarity to be had. As we’ve mentioned, the original location of the altarpiece was in a hospital. These people are the dying. What is particularly significant is that historically the altarpiece was left closed, except on a handful of Marian and other feast days, so that the exterior panel depicting the Crucifixion is what these sick and dying saw for the great majority of the time. The unrelenting realism of the way the body of Jesus is portrayed, both on the Cross in the central panel and in the Lamentation below—with an excruciatingly pockmarked body, skin of a sallow, greenish tinge, the disfigured limbs, even the central seam on the wood that bisects Jesus’ right arm and amputates the legs below the knees and the hand of the John the evangelist appearing very much like a crutch under the arm of the dead Jesus—mimic the horrific symptoms of the audience, including gangrene, lost limbs, skin discoloration, convulsive disorders, and permanent disfigurement. What greater solidarity with the suffering than for these patients to meet in the body of Jesus a reflection of their own suffering bodies?

Isenheim Altarpiece, first open position

Isenheim Altarpiece, first open position

Secondly, the audience would have known what hope and glory and sublimity lay just underneath the first panel: Annunciation and Nativity and especially Resurrection. In a very Johannine sense, then, the Cross is read as concomitantly the locus of suffering and death and the place of redemption and effervescent glory. As one commentator on the altarpiece rightly puts it, “seen against the Resurrection, the Crucifixion sheds any potential sadism and becomes a more complex image of a love beyond reason capable of assuming the greatest torment and miraculously triumphing over it.”[24] One way of elucidating this point is a consideration not only of Grünewald’s use of light and darkness, but also that of darkness and darkness.

The original location of the altarpiece was in a hospital. . . . What greater solidarity with the suffering than for these patients to meet in the body of Jesus a reflection of their own suffering bodies?

Compare, for instance, the quality of darkness in the first, exterior position of the Crucifixion to the bright, near living darkness that surrounds this Resurrected Christ in the middle position. In the former, the darkness is an absolute; it is black as pitch; it seems, indeed to have had the final word. But, in the Resurrection-Ascension panel, the darkness is lush—shot through with stars, floodlit by the large and brilliant halo behind the figure of the transfigured Christ, whose body still bears the marks of crucifixion on his hands and feet.[25] As Balthasar’s essay “Revelation and the Beautiful” observes, “the humiliation of the servant only makes the concealed glory shine more resplendently, and the descent into the ordinary and commonplace brings out the uniqueness of him who so abased himself.”[26] That the Isenheim Altarpiece is both of these together—both Crucifixion and Resurrection, death and glory in one installation—is quite theologically significant. The Johannine profile is clear, where suffering and glory are presented together. As Balthasar puts it, the Cross, “with all its terrors and feelings of abandonment, cannot shake for a moment the loyalty of the lover. He remains enclosed and protected within an unbreakable, crystalline form,”[27] which is, of course, the healing form of self-evacuating love.

“The ends of our fingers and beams of our eyes”: Poiesis, Attunement, and Eternal Youth

As we conclude our reflection, a consideration of the etymological roots of the word “poetry” is apropos. The ancient Greek root is ποιέω, which means, in its simplest definition, “to make.” In a sense, our hypothetical triptych of Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece and T.S. Eliot’s choruses from The Rock are various ways of giving expression—in forms as distinct in time as they are in genre—to the practice of making, of building or creating something, both in their content as well as in their own performance in poetry, short fiction, or in paint and wood. Even the various characters are “makers,” whether in the increasingly complex pen drawing in Carver’s story or the workers in Eliot’s The Rock building a Church with new stone, new timbers, even new speech:

The soul of man must quicken to creation.

Out of the formless stone, when the artist united himself with stone,

Spring always new forms of life, from the soul of man that is joined to the soul of stone;

Out of the meaningless practical shapes of all that is living or lifeless

Joined with the artist’s eye, new life, new form, new colour.

Out of the sea of sound the life of music,

Out of the slimy mud of words, out of the sleet and hail of verbal imprecisions,

Approximate thoughts and feelings, words that have taken the place of thoughts and feelings,

There spring the perfect order of speech, and the beauty of incantation.[28]

Part of what it is to be a Christian is to be young, and young in a way that has nothing to do with the passing of physical years.

Here at this juncture we might think about how forms of art can speak to forms of life, how this making of artwork can parlay thematically into the making (and even the healing) of a human life. Recall that Balthasar places great emphasis on the conjunction rather than the disjunction between the aesthetic and the ethical. Drawing from Rilke’s famous poem “The Archaic Torso of Apollo,” Balthasar states that “an apparent enthusiasm for the beautiful is mere idle talk when divorced from the sense of a divine summons to change one’s life.”[29] With Christ as the form of forms and the model which can imprint itself upon human lives, human beings are called to make themselves, in Balthasar’s language, “into God’s mirror and seek to attain to that transcendence and radiance that must be found in the world’s substance if it is indeed God’s image and likeness—his word and gesture, action and drama.”[30] Being a Christian, then, is itself a life-form, which opens up a particular “possibility of existence” attuned to its position as an individual member of the Body of Christ but situated ecclesially in the Church, and, as Balthasar puts it in no uncertain terms, “When it is achieved, Christian form is the most beautiful thing that may be found in the human realm.”[31]

Moreover, for Balthasar, part of what it is to be a Christian is to be young, and young in a way that has nothing to do with the passing of physical years.[32] One way of effecting this healing transformation, of being reborn to this eternal youth—and here I am following Balthasar directly—is the conscious cultivation of a sense of attunement “to the art of God.”[33] A child-like receptivity to beauty becomes a cipher or measure of the human capacity to know God and to love God, even to be evangelized at all. Balthasar suggests that one of the fundamental functions of poetry—and here we might extend this category to all those things artfully “made”—is a softening of the soul, the restoration and renewal of human beings “to a condition of openness” to eternity, to transcendence, to eternal childhood marked by a kind of gameness, a willingness to accept ordinary existence as a reality that is “what is wonderful: frightening and seductive, burdensome to the point of melancholy, yet inviting one to a secret, continual feast.”[34] Importantly, it is this “mysterious youthfulness” of the Word that for Balthasar marks the saints, more than any other characterization[35]

This sphere of openness is a sphere of healing, and it contains hidden within it, in Balthasar’s own words, “the goods of salvation: peace in God, beatitude and transfiguration, victory over sin, paradise present though concealed, all that the beautiful consoles us with.”[36] To be attuned and receptive enough to the immense and mysterious possibilities of the Christian life is, perhaps, to have our vision be healed—to learn to see again, like children, in a kind of transformative rhapsody that is drawing cathedrals with our eyes closed, conscious of the fact that the whole can and does shine luminously through these bright fragments of beauty, in what is a genuine encounter with the crucified and risen Christ.

In the spirit of this constitutively Christian attunement to poetic beauty, it seems only fitting to allow T.S. Eliot the last word, which is none other than a prayer and our benediction:

O Light Invisible, we praise Thee!

Too bright for mortal vision.

O Greater Light, we praise Thee for the less;

The eastern light our spires touch at morning,

The light that slants upon our western doors at evening,

The twilight over stagnant pools at batflight,

Moon light and star light, owl and moth light,

Glow-worm glowlight on a grassblade.

O Light Invisible, we worship Thee!

We thank Thee for the lights that we have kindled,

The light of altar and sanctuary;

Small lights of those who meditate at midnight

And lights reflected from the polished stone,

The gilded carven wood, the colored fresco.

Our gaze is submarine, our eyes look upward

And see the light that fractures through unquiet water.

We see the light but see not whence it comes.

O Light Invisible, we glorify Thee!

In our rhythm of earthly life we tire of light. We are glad when the day ends, when the play ends; and ecstasy is too much pain.

We are children quickly tired: children who are up in the night and fall asleep as the rocket is fired; and the day is long for work or play.

We tire of distraction or concentration, we sleep and are glad to sleep,

Controlled by the rhythm of blood and the day and the night and the seasons.

And we must extinguish the candle, put out the light and relight it;

Forever must quench, forever relight the flame.

Therefore we thank Thee for our little light, that is dappled with shadow.

We thank Thee who hast moved us to building, to finding, to forming at the ends of our fingers and beams of our eyes.

And when we have built an altar to the Invisible Light, we may set thereon the little lights for which our bodily vision is made.

And we thank Thee that darkness reminds us of light.

O Light Invisible, we give Thee thanks for Thy great glory![37]

![]()

[1] T.S. Eliot, The Rock: A Pageant Play, Written for Performance at Sadler’s Wells Theatre (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 7.

[2] Hans Urs von Balthasar, “Revelation and the Beautiful” in Explorations in Theology, Volume I, The Word Made Flesh, trans. A.V. Littledale and Alexandre Dru (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1989), 117.

[3] Raymond Carver, “Cathedral” in Collected Stories (Des Moines: Library of America, 2009), 525.

[4] Ibid., 527.

[5] Ibid., 528–29.

[6] Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, Volume I: Seeing the Form, [GL I], 2nd ed., trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, ed. Joseph Fessio, SJ and John Riches (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2009), 9.

[7] Ibid., 18.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 20.

[10] Ibid., 118.

[11] Ibid., 29.

[12] Hans Urs von Balthasar, A Theological Anthropology, trans. William Glen-Doepel (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1968), 226.

[13] “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 120.

[14] GL I, 32.

[15] “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 118.

[16] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Logic, Volume I: Truth of the World, trans. Adrian J. Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2001), 20.

[17] GL V, 33.

[18] Eliot, The Rock, 76.

[19] GL I, 124.

[20] GL II, 354-5.

[21] For wonderful scholarly commentaries on the historical, theological, and artistic subtleties of this important work, especially with an eye toward its hospital context, see Andree Hayum, The Isenheim Altarpiece: God’s Medicine and the Painter’s Vision (Princeton University Press, 1993), 20, and Robert Baldwin, “Anguish, Healing, and Redemption in Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece,” Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Issue 1 (Fall 1999/Spring 2000), 80-91.

[22] Hayum, 30.

[23] Baldwin, 82.

[24] Baldwin, 88.

[25] Ibid., 89.

[26] von Balthasar, “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 114.

[27] Ibid., 123.

[28] Eliot, The Rock, 75.

[29] von Balthasar, “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 107.

[30] GL I, 22.

[31] Ibid., 28.

[32] von Balthasar, A Theological Anthropology, 260.

[33] “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 126.

[34] A Theological Anthropology, 245.

[35] Ibid., 261.

[36] “Revelation and the Beautiful,” 111–112.

[37] Eliot, The Rock, 84–85.