How might we preach at the Liturgy of the Hours? On the one hand, what is unique about preaching in this context? Is there something about this setting which suggests a particular homiletic approach different from preaching at Sunday Eucharist? On the other, what does preaching at the Hours have in common with other forms of liturgical preaching?

For the sake of this essay, I will focus on the two “hinges” of the Liturgy of the Hours (LOH)[1]—Morning and Evening Prayer[2]—and will exclude special considerations such as preaching at the LOH in the context of funeral rites or Eucharistic Adoration.[3] Finally, I use the word “homily” to refer to the form of preaching which “flows from and immediately follows the scriptural readings of the liturgy and which leads to the celebration of the sacraments”[4] or to the non-sacramental rite being celebrated, whether the preacher is ordained or not.[5]

As in other forms of preaching, I would argue that the preacher at the LOH is challenged to attend to multiple factors in crafting his or her homily. To begin with, liturgical preaching is to be based on the Scriptures proclaimed in the context of the rite being celebrated.[6] According to the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (CSL) of Vatican II, the homily

is part of the liturgical service . . . [it] should draw its content mainly from scriptural and liturgical sources, being a proclamation of God’s wonderful works in the history of salvation, the mystery of Christ, ever present and active within us, especially in the celebration of the liturgy.[7]

So, while other texts—such as prayers and hymns—may supplement the Scriptures, the preacher is called to attend primarily to the biblical texts. At the same time, the preacher must also attend to the liturgical context: the particular rite being celebrated as well as its place in the broader liturgical calendar.

In addition to the text(s) in question, the preacher must also take into consideration the context of the assembly. The contemporary homiletic “turn toward the listener” urges us to take into account the individuals who make up each congregation, with their varied personalities, learning styles, and life experiences, as well as the overarching socio-cultural milieu in which the worshipping community is located; otherwise, we risk not being heard.[8] In the case of the LOH, one might ask: is this a parish group, or a community of religious? Are these clerics at a regular gathering, or seminarians or candidates for the diaconate in formation?

While Fulfilled in Your Hearing (FIYH) addresses preaching at Sunday Eucharist, its definition of the homily as “a scriptural interpretation of human existence which enables a community to recognize God’s active presence, to respond to that presence in faith through liturgical word and gesture, and beyond the liturgical assembly, through a life lived in conformity with the Gospel”[9] applies broadly to liturgical preaching. At the same time, each liturgical context—Sunday or weekday Eucharist, the sacraments, and non-sacramental rites—is distinct and therefore calls for a particular approach to preaching. How one preaches at Sunday Eucharist should “sound” different than how one preaches at a Baptism or a funeral. It is my hope in this essay to identify what makes preaching at the LOH distinct from preaching at Eucharist and the other rites, and, based on those distinctions, to offer an approach to such preaching.

The Liturgy of the Hours

In order to develop a homiletic approach particular to the LOH, an appropriate starting point is to review what the official documents of the Catholic Church say about this form of worship. Therefore, we begin with a brief overview of the General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours (GILOH).

The LOH in General:

Trinitarian, Christological, Ecclesiological

As with other forms of liturgical prayer, the LOH is profoundly Trinitarian.[10] In the LOH, the great deeds which God has done in creation and redemption are recalled, giving rise to praise and thanksgiving of God the Father. This prayer is made through the mediation of Christ and under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, who gathers the Church in unity.

To pray the Liturgy of the Hours is to exercise our baptismal priesthood.

The GILOH also reminds us that to celebrate the LOH is to encounter Christ, who is present “in the gathered community, in the proclamation of God’s word, ‘in the prayer and song of the Church.’”[11] By that “exchange or dialogue”[12] between God and the assembly, those who pray the LOH—to the degree that their minds and voices are in harmony (that is, they are not simply reading the words but praying in and through Christ)—are sanctified by God’s grace and transformed more and more into the likeness of Christ.[13]

Traditionally, the psalmody of the Hours has been viewed as a privileged locus of encounter with Christ, first because these are the prayers that he used; we get to know him by learning how he prayed.[14]As Pope St. John Paul II wrote: “We pray the same psalms that Jesus prayed and come into personal contact with him.”[15] Yet, such knowing is not limited to the past. As the Body of Christ, when we pray the psalms, Christ is praying with and for us to the Father.[16] We also encounter Christ through the psalms because, as Christians, we see in some of them a foreshadowing of his coming as Messiah; the psalms are not only prayers of and with Jesus, but prayers to Christ.[17]

To pray the LOH is to exercise our baptismal priesthood. We join our voices with all those who have sung God’s praises throughout the ages; we also receive “a foretaste of the song of praise in heaven.”[18] In addition, through the celebration of the LOH we intercede for the living and the dead.[19] It is especially important to note that, in praying the psalms as part of the LOH, individuals do not pray in their own name but “in the name of the entire Body of Christ,”[20] the Church.

GILOH: Implications for Preaching

If preaching is to be integral to the liturgy being celebrated,[21] then any preaching event should somehow respect or reflect its particular ritual context. Given the brief synopsis of the Church’s theology of the LOH above, I would therefore propose that, to begin with, preaching at the LOH should:

- help the assembly give praise and thanksgiving to God;[22]

- help those in the assembly encounter Christ in their midst[23] (in the liturgical assembly and in their daily lives, and in those whose voices are echoed in the psalms); and

- help the assembly bring their minds and voices into harmony, that is, to enter more deeply into the Prayer of the Church and so be more open to the working of the Holy Spirit—the Spirit of unity.[24]

That is, preaching ought to be Trinitarian, Christological, and ecclesial.

The GILOH itself, however, is rather succinct when it comes to preaching: “In a celebration with a congregation a short homily may follow the reading to explain its meaning, as circumstances suggest.”[25] Given the development of homiletics after Vatican II, I would argue that the phrase “explain its meaning” should be taken to refer to something more than simply providing a catechetical lesson on the Bible or a theology lecture.[26] Rather, the preacher is called upon to help the assembly “make meaning” by looking at life through the lens of the Scriptures. As FIYH reminds us, those who gather for worship are “hungry, sometimes desperately so, for meaning in their lives.”[27]

Other Considerations: Implications for Preaching

In Preaching to the Hungers of the Heart, James Wallace looks beyond the question of preaching at Sunday Eucharist to address how one might approach preaching on the feasts of the Lord or of the saints and Mary, as well as in the context of the Church’s other sacramental rites. In each of these settings, Wallace postulates that preaching should address a particular “hunger” in the hearts of the assembly.

For Wallace, the feasts of the Lord “respond to an appetite we have to connect our life with something that speaks to the deepest level of our being”[28] while the feasts of the Saints and Mary address our hunger for belonging, that is, “connectedness, community, and companionship.”[29] In the context of celebrating the sacraments, preaching addresses the need to make meaning in the midst of key transitional moments and assists the assembly to become fully engaged in the rite.[30] It seems to me that preaching at the LOH is in some ways analogous to preaching at the feasts and rites. In other words, depending on the particular liturgical focus—the saints or Mary, the liturgical season (including the feasts of the Lord), or the recurring cycle of the 4-week psalter—the preacher is able to focus his or her homily on addressing the assembly’s hunger for belonging, wholeness, or meaning.

A Homiletic Approach

“By tradition going back to early Christian times, the Divine Office is so arranged that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praises of God.”[31]

Therefore, preaching particular to this setting must take this focus on time seriously.

“Sanctifying the Day”

According to the GILOH, “the purpose of the liturgy of the hours is to sanctify the day and the whole range of human activity.”[32] But what does such a phrase mean? Surely we cannot insist, in a Pelagian fashion, that by our actions we make holy what was not previously holy. Rather, we would do well to view time through a sacramental lens:

The experience of reality tells us that time like all else created is a sacrament—both a revelation of, and therefore a communion with, God. . . . The purpose of the Divine Office with regard to time is to transform our experience of time by at once revealing and restoring its ontological—that is, its divinely-intended—holiness, its sacramentality as revelation of, and communion with, God. In this sense, and in this sense alone, the phrase “the sanctification of time” may be used of the purpose of the divine office.[33]

Therefore, it is in the daily unfolding of time—and in linking the celebration of the LOH to that unfolding—that the LOH is analogous to the celebration of the sacraments. While the sacraments use the stuff of earth and human labor to mediate a transformative encounter between Christ and those gathered for liturgy, the LOH uses time in the same manner.

Therefore, it is in the daily unfolding of time—and in linking the celebration of the LOH to that unfolding—that the LOH is analogous to the celebration of the sacraments. While the sacraments use the stuff of earth and human labor to mediate a transformative encounter between Christ and those gathered for liturgy, the LOH uses time in the same manner.

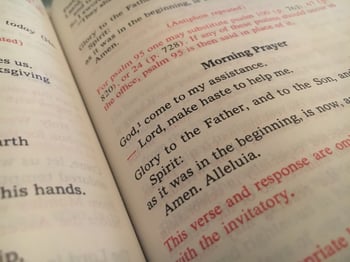

According to the GILOH, Morning Prayer[34] is oriented towards consecrating the day to God; the Resurrection is the aspect of the Paschal Mystery which is highlighted. Preaching, therefore, also ought to be “future-oriented”—acknowledging a radical dependence on God while looking ahead to the day with hope and expectation, helping the assembly to discern what resurrection life might look like here and now.

Evening Prayer,[35] on the other hand, is more retrospective in orientation. The day is recalled, both with praise and thanksgiving as well as acknowledging the need for forgiveness. Therefore, the aspect of the Paschal Mystery which is emphasized is the redemption Christ has accomplished, while the prayers at this Hour focus on petition. Preaching in this setting can serve to help the assembly offer their prayer as a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving.

The Temporal Cycle

The celebration of the LOH takes place in the context of a particular liturgical season. As Pope Pius XII said, the liturgical year “is not a cold and lifeless representation of the events of the past, or a simple and bare record of a former age. It is rather Christ Himself who is ever living in His Church.”[36] By this continuous encounter with Christ, the liturgical calendar shapes “us into a people who moves through these periods in a very deliberate way, allowing them to draw us into the mystery of Christ through an annual recognition of particular seasons and feasts.”[37]

By that “exchange or dialogue” between God and the assembly, those who pray the Liturgy of the Hours—to the degree that their minds and voices are in harmony (that is, they are not simply reading the words but praying in and through Christ)—are sanctified by God’s grace and transformed more and more into the likeness of Christ.

Theologically, each of the liturgical seasons highlights a particular aspect of the Paschal Mystery; together, they draw us deeper into that mystery and animate us.[38] The characteristics of each season help to focus the homily; preaching with the seasons in mind helps us to encounter Christ in a particular way. Structurally, the liturgical calendar may be divided into two major cycles: Advent-Christmas and Lent-Easter, which are in turn separated by periods of Ordinary Time.

In Advent, the Church remembers Christ’s coming in history, celebrates Christ continued coming in our midst, and looks forward to Christ’s coming at the end of time; it is therefore “a period for devout and expectant delight,”[39] a time of “exclamation and excitement.”[40] The Christmas season proclaims the presence of God in human history[41] by emphasizing the mystery of the Incarnation. By preaching at a succession of feasts that recall the birth and early manifestations of Christ, the homilist is challenged to draw out what implications such a mystery has for the life of the Christian today.[42]

The focus of Lent is conversion in response to Christ’s call: for the Elect on their journey to the font as well as for the faithful, recalling their own Baptism and preparing to renew their baptismal promises as they accompany the catechumens. Therefore, the season has a penitential character, drawing us to a deeper commitment to Christ.[43] The mystery of Christ’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection are recalled at the Easter Triduum—and celebrated as “one great Sunday” for 50 days.[44] The implications of resurrection life inform preaching in this season.[45] Rather than highlighting a specific facet of the Paschal Mystery, during the seasons of Ordinary Time “the mystery of Christ itself is honored in its fullness.”[46]

In the midst of the liturgical seasons, the Church also celebrates particular feasts of the Lord. On these “solemn feasts we remember and make present [anamnesis] the salvation brought into being through particular events in human history [Paschal Mystery].”[47] Preaching in this context must not only be attentive to the liturgical season, but also to the way that the feast sheds light on the identity of the Christian community, as well as its manner of being in the world.[48] As we encounter these feasts throughout the year, Wallace argues that the preacher’s emphasis ought to be on helping the listener “connect” to a deeper story—the Paschal Mystery—by attending to the biblical and liturgical texts as well as to other conversation partners, such as current events and the arts.[49] By helping listeners see themselves as part of the story, the preacher is able to help them move from simply recalling past events to encountering Christ in the present.

The Sanctoral Cycle

In addition to the temporal cycle of the liturgical seasons, the Church also observes the sanctoral cycle, by which it “venerates with a particular love the Blessed Mother of God, Mary, and proposes to the devotion of the faithful the memorials of the martyrs and other saints.”[50] Preaching on the feasts of the saints and Mary should not be an exercise in hagiography; rather, “the place of the saints within preaching is constrained . . . by the nature of the liturgical homily as an act of biblical interpretation of life.”[51] The saints are preached in order to point to Christ, so as to help the assembly see that the Paschal Mystery, which was so powerfully present in the lives of the saints, is present in their lives as well.[52] As with the saints, when preaching on the Marian feasts, the homilist is cautioned not to replace Christ with Mary, but to use her story to help the community see in itself the place of God’s ongoing salvific work.[53] Therefore, Wallace suggests that in preaching we would do well to speak of the saints as mirrors (who reflect a particular aspect of God revealed in the scriptural text), models (of what life in response to God’s grace might look like), mentors (to the community of faith), and even metaphors (for graced human nature).[54]

Summary: Additional Principles for Preaching at the Hours

After reviewing the theology of the LOH, paying particular attention to the importance of time in this liturgy, we can add that in addition to being Trinitarian,[55] Christological,[56] and ecclesial[57] in character, preaching at the LOH ought to:

- be solidly biblical,[58]

- deepen the community’s understanding and celebration of the Hour being observed, and

- move the community to live out the implications of what “sanctifying time” really means—that Jesus Christ is not confined to history but is present here and now, that our time and seasons are also the work of God, and that there is nothing unrelated to the divine;[59] that is, to “name grace”—the manifestation of the Paschal Mystery in the present.[60]

In other words, preaching at the LOH ought also to be sacramental.[61] While other rites offer us the opportunity to encounter Christ through material creation, the LOH highlights the sacramentality of time. It is through the micro-cycle of each day, as well as through the macro-cycle of the seasons (liturgical and cosmic; temporal and sanctoral), that we are given a particular opportunity to encounter Christ. Preaching, therefore, ought to help us make meaning out of the daily and seasonal unfolding of our lives, much like preaching at the rites helps us make meaning out of significant or transitional events in our lives. And just as preaching in the rites moves us to celebrate the sacraments more fully,[62] so preaching at the LOH might move us to celebrate the LOH more fully, with hearts and voices in harmony.[63]

By helping listeners see themselves as part of the story, the preacher is able to help them move from simply recalling past events to encountering Christ in the present.

Finally, preaching at the LOH ought to be rooted in the Paschal Mystery.[64] The LOH places us in relationship with a story much greater than ourselves as well as with a community that has lived and continues to live that mystery as time unfolds (the Communion of Saints). Preaching, therefore, should help us make those connections—to feed the hunger to be whole and to belong.

Homiletic Form and Content

As with the sacramental rites, the homilist is cautioned to be brief when preaching at the LOH.[65] Given the overall length and flow of Morning and Evening Prayer, preaching that is 2 to 4 minutes in length would not be unreasonable. Therefore, the preacher must be particularly intentional in discerning both the core message (content) of his or her homily as well as the way he or she will structure that message (form).

Content: Focus and Function

The task of the preacher is to move from text to homily: what the text tries to say and do ought to be, at least according to Thomas Long, what the homily says and does.[66] Long refers to these two ways of approaching homiletic intention as the “focus” and “function” of the homily, respectively. He defines the focus of a homily as a “concise description of [its] central, controlling, and unifying theme” and the function of a homily as “a description of what the preacher hopes the sermon will create or cause to happen for the hearers.”[67] For Long, these two statements must flow directly from the biblical texts, be simply and clearly stated, and work as a unified whole.[68] In preaching at the LOH, the context of the temporal and sanctoral cycles, as well as the particular Hour being celebrated, should also be taken into consideration when determining the focus and function of a homily.

Form: Deductive vs. Inductive[69]

Homiletic form refers to “an organizational plan for deciding what kind of things will be said and done in a sermon and in what sequence.”[70] Given the usual length of time given to preaching at the LOH, the typical homiletic forms[71] used in Sunday preaching would need to be significantly adapted for use in this context. The final form of a homily, whether deductive or inductive, ought to be determined both by the genre or “shape” of the text(s) being preached on as well as the “listening patterns” of those in the assembly.[72]

A group of Notre Dame undergraduates prays Vespers together; photo courtesy of the Institute for Church Life.

A group of Notre Dame undergraduates prays Vespers together; photo courtesy of the Institute for Church Life.

Until the last half of the twentieth century, typical preaching was deductive—or propositional—in style; what Richard Jensen refers to as “thinking in idea.”[73] Following a logical outline, such a “sermon” is more akin to a lecture than a conversation; it seeks to inform the listener. Moving from the general to the specific, deductive preaching takes a “top-down” approach in arguing for or trying to prove a point. Deductive preaching has been criticized for being authoritarian in approach and often only tangentially related to the scriptural text(s).

In the latter half of the last century, homileticians turned their attention to the place of the listener in preaching. In other words, they have sought to structure preaching in a way that corresponds to the way that we naturally converse: inductively. Inductive preaching moves from the specific to the general, and unfolds in a narrative fashion; it is reflective of a more communal model of ministry and more intimately connected to the scriptural texts. Therefore, Jensen refers to such an approach as “thinking in story.”[74] Inductive preaching is reflective of the performative nature of language, values experience, and makes space for an encounter; it forms and transforms—not merely informs.

More recently, some homiliticians have urged a move beyond the inductive to the imaginal. According to Richard Eslinger, “to preach in nonimagistic ways is in this postmodern context to lose the vernacular of our people.”[75] The use of images in preaching—whether visual or linked to any of the other senses—is more than just rhetorical flourish; images are how we come to know. They mediate “between the self and the world.”[76] In the words of Jensen, the preacher must “think in image.”[77] A homily in this mode of preaching might be structured as a series of images—either contemporary or historical/biblical—all reflective of a central theme or master image derived from the Scriptures. Given such a fluid model, it could easily be adapted to preaching at the LOH.

A Form Particular to the LOH

Alternatively, a different homiletic form could be proposed: one which more closely mirrors the structure of the major Hours themselves. According to Stanislaus Campbell, the “deep structure” of the Paschal Mystery is reflected in the LOH: God calls or acts on the behalf of creation; human persons respond in worship and by living a life consonant with God’s call.[78] A similar dynamic is presented in Preaching the Mystery of Faith (PMF): our liturgical encounter with Christ—mediated, in part, by the homily—ought to lead to interior conversion as well as external action (praise and thanksgiving, mission).[79] Such reflections are consonant with sacramental theologian Louis-Marie Chauvet’s proposal that the liturgy is marked by a dynamic of gift—reception and return-gift.[80] Perhaps preaching at the LOH might reflect Chauvet’s model by being structured along the lines of three “moves.”[81]

In the first move, God’s actions on behalf of the human race—the reasons for the assembly’s praise and thanksgiving—are recalled (anamnesis). While the primary source for preaching is the assigned reading, it must also be remembered that the liturgical season or feast (temporal cycle) or saint (sanctoral cycle) being celebrated also helps to focus the reason for the assembly’s praise and thanksgiving. In the second move, the echo of that event in the present is named. Here we see how the LOH are linked to the very ordinariness of life and the unfolding of time. In other words, the preacher names how the “gift” given in history is now “received” in the present—where and how Christ is being encountered, and how the assembly is being transformed as a result. Finally, in the third move, the preacher explores how the assembly responds to that gift-made-present. On the one hand, to make return-gift implies offering the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving called for by the LOH.[82] In that sense, the preacher may reflect on entering more deeply into the prayer itself (bringing minds and voices into harmony). On the other hand, to make return-gift has ethical implications as well. For Chauvet, the Christian life is built on the interrelationship of Scripture, sacrament, and ethics.[83] The return-gift called for by celebrating any liturgy must include living a life consonant with the Reign of God; therefore, helping the assembly to draw out those implications is an important task for the preacher at the LOH as well as at the Eucharist.[84] Such implications may be spoken of in terms of resurrection life (Morning Prayer) or in terms of our ongoing need for redemption (Evening Prayer).

In FIYH, the U.S. Bishops recommend that the homilist begins with “a description of a contemporary human situation which is evoked by the scriptural texts” and then turn his or her attention “to the Scriptures to interpret this situation” and conclude with “an invitation to praise this God” who is present in the lives of the assembly.[85] While Chauvet’s model appears to be sequential (gift → reception → return-gift), these three elements are related structurally rather than chronologically and his model is more a process than a series of static steps.[86] Therefore, alternatively, it may be preferable to structure the homily so as to begin with the lived situation of the assembly (present) first—as I have done in the example homily below.

Conclusion

In addition to the Eucharist and the other sacraments, the Roman Catholic Church proposes that the LOH is intended to be the prayer of the entire Christian community, not just of clerics and religious.[87] A homiletic particular to this form of liturgical prayer will share features with liturgical preaching in general, but will also be respectful of what is unique about this setting. As detailed above, in addition to being necessarily brief, preaching at the LOH ought to be, after Chauvet:

- Biblical: rooted in the Scriptures themselves and in the ways the scriptures are echoed in the Church’s prayers;

- Sacramental: but in the case of the LOH, the sacramental encounter with Christ is mediated primarily by time rather than matter; and

- Ethically-oriented: participants should be transformed by their participation in the LOH—moved to faithfully respond to God’s initiative with praise and thanksgiving (Trinitarian), to embrace a deeper unity as brought about by the Holy Spirit (ecclesial), and to live Christ’s Paschal Mystery (Christological) in their own lives.

In other words, the LOH helps bring about an encounter with the divine, an encounter initiated by God and mediated by Scripture, preaching, and prayer—an encounter that is transformative and calls from the faithful a response in faith. This response not limited to the offering of prayer and thanksgiving in the context of the liturgy, but calls for a liturgical life—a life characterized by the offering of self in love of God and neighbor. Given this dynamic, I have proposed a homiletic—based on the work of Louis-Marie Chauvet—that accounts for the particularities of this form of communal prayer, and reflects this pattern of encounter (gift), transformation (reception), and sacrifice (return-gift).

Sample Homily for LOH

Occasion: Morning Prayer with candidates for the diaconate and their wives (Deacon Formation)

Feast: Solemnity of the Ascension (May 16, 2010)

Reading: Hebrews 10:11–14

Move 1 (present)

The Feast of Betwixt-and-Between.

That’s what I’d call today’s celebration, if I had to rename it.

Because that’s where we sit: in betwixt-and-between time.

And at least it sounds a little more theological than

the “Feast of Between a Rock and a Hard Place . . .”

Like the time when we were adolescents . . .

No longer children but not yet adults.

Like the time when we were engaged . . .

No longer single but not yet married.

Like you being candidates now . . .

No longer simply lay parish volunteers, but not yet ordained.

Like that terrible time . . .

The time between death and burial . . .

between life as it used to be and beginning to put the pieces back together again . . .

Betwixt-and-between time . . .

It’s never easy.

Move 2 (past)

The same is true of the Christian life.

On the one hand, for 2000 years the Church has been proclaiming the Good News that the Resurrection has changed everything.

That Christ’s “one sacrifice for sins” has redeemed us . . .

That the Reign of God is here and now.

On the other, for 2000 years we’ve also seen that it seems as if precious little has really changed.

Just read the paper . . . or watch the news for 30 seconds . . . it’s easy to see . . .

That we still have to wait for Christ’s enemies—sin and death—to be made his footstool.

That the Reign of God is not yet.

It may be tempting just to give up . . .

Drift away from the life of faith . . . like those the preacher of Hebrews was talking to . . .

Betwixt-and-between time . . .

It’s never easy.

Move 3 (future)

The Feast of Betwixt-and-Between.

It’s not just one day . . . but it’s where we live . . .

Between Jesus walking the earth . . . and Christ’s return at the end of time . . .

And it’s not easy.

So the angel speaks to us, too:

Men (and women) of the Davenport Diocese . . . why are you looking up into the sky?

In other words: Don’t just stand there! Moping. Wishing things were otherwise.

Follow Christ into the new creation . . .

In whatever way Christ is calling you . . .

Rejoicing . . . for Christ’s Ascension is our glory and our hope.

![]()

Featured Photo: The Dominican Friars of the St. Joseph Province; CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

[1] While written from the perspective of the Roman Catholic tradition, I hope that this essay might find resonances in other communities as well.

[2] Lauds and Vespers, respectively.

[3] There are many occasions at which a community might pray the Liturgy of the Hours, and the particulars of such occasions should certainly inform both the form and the content of the preaching.

[4] Robert P. Waznak, SS, “Homily” in The New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship, ed. Peter E. Fink (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1990), 552.

[5] The issue of lay preaching in the Roman Catholic tradition is complex, and not the focus of this essay. Suffice it to say that only ordained ministers are permitted to preach the homily at the Eucharist. However, properly deputed lay men and women may preach in other settings. See canons 766–767 in the Code of Canon Law (CCL) and in the complementary norms issues by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB); see also the interdicasterial instruction, Ecclesia de Mysterio (EM), §3, ##1 and 4. CCL tends to use the term “homily” to refer to preaching by the ordained; both EM and the General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours (GILOH) use the term more broadly.

[6] Bishops’ Committee on Priestly Life and Ministry, National Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Homily in the Sunday Assembly” (FIYH, 1982) in The Liturgy Documents, vol. 1, 5th ed. (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2012), §50.

[7] Second Vatican Council, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (1963) in The Liturgy Documents, vol. 1, 5th ed. (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2012), §35. See also CSL §52, FIYH §42, and Committee on Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Preaching the Mystery of Faith: The Sunday Homily (PMF), 18, 20, 22.

[8] Guerric DeBona, OSB, Fulfilled in Our Hearing: History and Method of Christian Preaching (New York: Paulist Press, 2005), 18–23. See also FIYH §§4, 8–11 and PMF, 33n43. PMF specifically mentions that homilies are not to be “abstract” (28, 33, 35, 41).

[9] FIYH §81. See PMF, 34–35.

[10] Congregation for Divine Worship, General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours (1971), in The Liturgy Documents, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2012), §§6, 8; see also Sister Janet Baxendale, “The Spiritual Potential of the Liturgy of the Hours” in Assembly vol. 32, no. 3 (May 2006), 20.

[11] GILOH §13.

[12] Ibid., §14. This dynamic has implications for preaching; see PMF, 7–8.

[13] Ibid., §19; see also Baxendale, 21.

[14] Richard Atherton, Praying the Psalms in the Liturgy of the Hours: New Light on Ancient Songs (Liguori, MO: Liguori, 2004), 16; Gregory J. Polan, OSB, “Discovering Christ in the Psalms” in The Bible Today, vol. 48, no. 3 (May/June 2010), 150–51.

[15] John Paul II, Address, Morning Prayer at St. Patrick’s Cathedral (3 October 1979).

[16] Atherton, 17–18; Polan, 152.

[17] Ibid.; Polan, 152–53.

[18] GILOH §16.

[19] Ibid., §§17–18.

[20] Ibid., §108. See also Atherton, 16; Baxendale, 22–23; Marc Girard, “The Psalms of Lament” in The Bible Today, vol. 48, no. 3 (May/June 2010), 141; Harry Hagan, OSB, “Praying Other People’s Prayers” in The Bible Today, vol. 48, no. 3 (May/June 2010), 144; Elizabeth Nagel, “Psalms of Praise and Thanksgiving: Responses to God’s Gracious Loyalty” in The Bible Today, vol. 48, no. 3 (May/June 2010), 133–34.

[21] CSL §§35, 52. See PMF, 19–20.

[22] FIYH §13; DeBona, 89, 135. See PMF, 20, 31, 37, 43.

[23] FIYH §19. See PMF 3, 6, 20, 21, 27–8.

[24] GILOH §8. See PMF, 9–10.

[25] Ibid., §47.

[26] FIYH §§43, 52. The importance of doctrinal content in preaching is a key feature of PMF (23–31, 35). However, it is made clear that “doctrine is not meant to be propounded in a homily in the way that it might unfold in a theology classroom or a lecture for an academic audience or even a catechism lesson. The homily is integral to the liturgical act of the Eucharist, and the language and spirit of the homily should fit that context” (26).

[27] FIYH §13. See PMF, 17, 28.

[28] James A. Wallace, Preaching to the Hungers of the Heart: The Homily on the Feasts and within the Rites (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002), 30.

[29] Ibid., 109.

[30] Ibid., 72.

[31] CSL §84.

[32] GILOH §11.

[33] Stanislaus Campbell, “The Paschal Mystery in the Liturgy of the Hours” in Liturgical Ministry, vol. 15 (Winter 2006), 55.

[34] GILOH §§38, 181; Campbell, 53, 55.

[35] GILOH §39, 180; FIYH §77; Campbell, 53, 55.

[36] Pius XII, Mediator Dei (1947), §165.

[37] Wallace, 35. See PMF, 28.

[38] DeBona, 94; Wallace, 44.

[39] Sacred Congregation of Rites, Universal Norms for the Liturgical Year and the General Roman Calendar (UNLYC, 2010), in The Liturgy Documents, vol. 1, 5th ed., (Chicago: The Liturgical Press, 2012), §39.

[40] Wallace, 47–48. PMF adds that Advent is also a time for “reflection on the ultimate purpose and direction of our lives” (28).

[41] Diane Bergant and Richard Fragomeni, Preaching the New Lectionary: Year C (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 31; PMF, 28; adding the gift of life as another theme.

[42] UNLYC §32; Wallace, 48.

[43] Ibid., §27; Wallace, 44–46. Echoed in PMF, 28.

[44] Bergant, 132; UNLYC §18, 22. PMF adds “the dynamic gift of the Spirit in our lives at Pentecost” (28).

[45] Bergant, 162; Wallace, 47.

[46] UNLYC §43.

[47] Wallace, 31.

[48] Ibid., 31, 34.

[49] Ibid., 37–40.

[50] UNLYC §8

[51] Wallace, 120.

[52] Ibid., 122. See PMF, 45.

[53] Ibid., 163

[54] Ibid., 124, 163–66.

[55] PMF, 8, 29.

[56] Ibid., 21–22.

[57] Ibid., 34–37.

[58] PMF, 6–7, 34, 39, 49–50. As with all liturgical preaching, preaching at the LOH should always be rooted in the scriptural text. While it may be enriched by other texts (in the case of the LOH, the psalms, canticles, hymns, and prayers assigned to the hour), the primary focus is the reading.

[59] Baxendale, 22–3.

[60] DeBona, 99–100. The Paschal Mystery is a central theme in PMF; see 9, 16–18. Also see Mary Catherine Hilkert, OP, Naming Grace: Preaching and the Sacramental Imagination (New York: Continuum, 1997). According to Wallace (80), all liturgical preaching ought to (1) be Scripture-based, (2) deepen the community’s understanding of the sacrament being celebrated, and (3) move the community to live out the implications of celebrating that sacrament. These three characteristics of liturgical preaching also feature prominently in PMF: see, e.g., example, 6–7, 34, 39, 49–50; 10, 22–23, 35; and 21, 28, respectively.

[61] In terms of Eucharist, see PMF 10, 22–23, 35.

[62] FIYH §52.

[63] GILOH §19.

[64] PMF, 9, 16–18.

[65] GILOH §47.

[66] Thomas G. Long, The Witness of Preaching (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1989), 86.

[67] Ibid., 86.

[68] Ibid., 86–91.

[69] See FIYH §65; DeBona, 5–32; Richard L. Eslinger, The Web of Preaching: New Options in Homiletic Method (Nashville: Abingdon, 2002), 15–56; and Long, 92–95 for a more detailed history of the development of the “New Homiletic” and critique of the previous, deductive approaches to preaching.

[70] Long, 93.

[71] In addition to the works by Thomas Long and Fred Craddock, see the specific models proposed by Eugene Lowry (“Lowry’s Loop” in The Homiletical Plot: The Sermon as Narrative Art Form, expanded ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), Paul Scott Wilson (“Four Pages” in The Four Pages of the Sermon: A Guide to Biblical Preaching. Nashville: Abingdom Press, 1999), and David Buttrick (“Moves” in Homiletic: Moves and Structures. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987).

[72] Long, 96, 104.

[73] See Richard A. Jensen, Envisioning the Word: The Use of Visual Images in Preaching (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 124–141.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Eslinger, 280.

[76] Ibid., 251.

[77] Jensen, 124–141.

[78] Campbell, 53. In the psalmody, for example, God’s redemptive actions are recalled; in the preces, the community responds with praise and petition (Campbell, 54; GILOH §§180–83).

[79] PMF, 12, 20–21.

[80] Louis-Marie Chauvet, Symbol and Sacrament: A Sacramental Reinterpretation of Christian Existence (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1995), 266–316. For example, in the Eucharistic liturgy, the gift (past) comes to us as Scripture, the gift is received (present) as sacrament in the mode of thanksgiving, and the return-gift (future) is made as living as the Body of Christ (Chauvet, 278). However, Chauvet does not intend his model to be taken as literally sequential (see below).

[81] The “moves” may not be as rigidly structured as Buttrick intends. For example, post-modern imaginal preaching (Eslinger, 246–287) may consist of “a series of storied fragments” reflective of a particular theme or “master image” but not necessarily connected to each other.

[82] See note 21 above.

[83] Chauvet, 161–189.

[84] See PMF 21, 28.

[85] FIYH §65. PMF states that the teaching of FIYH in this regard remains valid (3, 6, 33n43, 50), explicitly stating that “the goal of the homily is to lead the hearer to the deep inner connections between God’s Word and the actual circumstances of one’s everyday life” (33; see also 34).

[86] Chauvet, 280.

[87] CSL §§83–85, 100.