Introduction: The Catholic Turn of the Word

The year is 1961. Father Smith, longtime Irish pastor of St. Mary’s Parish, has just concluded the reading of the Gospel—in Latin, of course. The people are seated, and Smith begins the announcements. “The Knights of Columbus will be having their monthly Fish Fry this Friday. . . . The Ladies’ Sodality is collecting canned goods for the poor. . . . Don’t forget the Rosary after the 6:30 a.m. Mass every Wednesday.” A long pause. “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.” Another pause. Then the pastor launches into the sermon, the last of a series on the Ten Commandments, this one covering the Ninth and Tenth Commandments.

Excoriating the materialism and acquisitiveness of modern American society, the priest works in a story about a Catholic high school boy with a pinup picture taped to the inside of his locker, leading to a stern reminder of the importance of regular Confession to cleanse sin from the soul. He closes with a Hail Mary, invoking the Mother of the Savior as both Mother of Dolors and Mother of Mercies. “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.” He resumes the Mass, praying solemnly in a language which few in the church can understand. Yet most of the congregants depart with a sense of having touched, fearfully yet really, the mystery announced by the “confection” of the Eucharist.

The foregoing vignette is composite fiction, of course, but a scenario that could have been played out in scores of Catholic parishes before the Second Vatican Council. The sermon—if, indeed, there was a sermon at all, since it was regarded as unnecessary and quite secondary to the Holy Eucharist, and thus optional—was generally approached as a moment to teach the assembled people and remind them of their moral and sacramental duties as Catholics. It was not necessarily connected either to the Scripture readings or to the Eucharistic Prayer (the Roman Canon), but represented rather a few moments of interlude between the two. Indeed the entire Liturgy of the Word was but a preamble to the Holy Sacrifice which was the sole reason and obligation of the Sunday gathering.[1]

The Second Vatican Council ushered in a revival of Catholic liturgical preaching, a revival based in part on a theological reconsideration of the importance of the Word. Half a century of renewed study of the liturgical sources preceded the Council’s adoption of Sacrosanctum Concilium: The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (1963). Scholars like Josef Jungmann, Otto Semmelroth, Karl Rahner, Yves Congar and Edward Schillebeeckx led the ressourcement and were deeply impressed with the early Church’s devotion to the proclamation and preaching of the Word of God.

In perhaps its most important theological contribution, Sacrosanctum Concilium broadened the understanding of the divine presence to include not only the Eucharistic elements of the Body and Blood of the Lord, and the priest as alter Christus, but also the Word and the assembly itself (cf. Sacrosanctum Concilium, §7). Catholics had been taught to revere the “Real Presence” residing in the bread and wine, and in the Church’s minister who acted in persona Christi, but the notion of God also present in the Word and in the community struck many as inexplicably new and perhaps even suspiciously Protestant. Fifty years on, the Council’s fourfold understanding of the liturgical divine presence has profoundly changed and enriched Catholic practice and spirituality, even while it remains a catechetical challenge.

Sacrosanctum Concilium broadened the understanding of the divine presence to include not only the Eucharistic elements of the Body and Blood of the Lord, and the priest as alter Christus, but also the Word and the assembly itself.

Flowing from this broadened understanding of God’s presence, Sacrosanctum Concilium then called for a revision of the Lectionary to provide “a more ample, more varied, and more suitable selection of readings from sacred scripture,” and emphasized that preaching “is part of the liturgical action” and “should be carried out properly and with the greatest care” (SC §35). Turning away from the practice of preaching based on other sources, the Council Fathers stated that preaching at Mass should be drawn from the Scriptures and the liturgy itself, “for in them is found the proclamation of God’s wonderful works in the history of salvation, the mystery of Christ ever made present and active in us” (SC §35). Moreover, Sacrosanctum Concilium was quite explicit about the homily’s importance and its integral place in the liturgical action:

By means of the homily, the mysteries of the faith and the guiding principles of the Christian life are expounded from the sacred text during the course of the liturgical year. The homily is strongly recommended since it forms part of the liturgy itself. . . . It should not be omitted except for a serious reason. (SC §52)

Although the document did not give a full account of the meaning of the homily “as part of the liturgy,” the larger context in which this claim is placed strongly emphasizes the seamless and unbreakable integration of what we have traditionally called Word and Sacrament. In the conciliar thinking, these are but two aspects of one whole experience of worship.

Two years later the Council gave an even stronger declaration of the integral role of preaching in the context of worship. In Presbyterorum Ordinis: The Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests, the Council Fathers astounded some by stating, “It is the first task of priests as co-workers of the bishops to preach the Gospel of God to all” (PO §4). The primacy of preaching in the life of priests was connected to the Word’s power to evoke faith:

For by the saving word of God faith is aroused in the heart of unbelievers and is nourished in the heart of believers. By this faith then the congregation of the faithful begins and grows, according to the saying of the apostle: “Faith comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes by the preaching of Christ” (Rom 10:17). (PO §4)

The conclusion is that preaching is an essential dimension of worship:

The preaching of the word is required for the sacramental ministry itself, since the sacraments are sacraments of faith, which is born of the word and is nourished by it. This is especially true of the liturgy of the word within the celebration of Mass where there is an indivisible unity between the proclamation of the Lord’s death and resurrection, the response of the hearers and the offering itself by which Christ confirmed the new covenant in his blood. In this offering the faithful share both by their prayer and by the reception of the sacrament. (PO §4)

If any doubt still remained about the Council’s intention to re-situate the homily firmly within the total experience of worship and reestablish its importance within the entire experience of worship, Pope Paul VI made the matter clear within a few years. In a 1965 encyclical entitled Mysterium Fidei: The Doctrine and Worship of the Holy Eucharist, the Pope even goes so far as to assert explicitly that Christ’s presence is found in the Church’s ministry of preaching (cf. MF §36).

Generally, though not consistently, official documents in subsequent years have continued to reiterate the divine presence in proclamation of the Word, the vital necessity of preaching as part of that proclamation, and the nature of the homily as itself an act of worship. The landmark 1982 document Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Homily in the Sunday Assembly, for example, says this:

A homily is not a talk given on the occasion of a liturgical celebration. It is “a part of the liturgy itself.” In the Eucharistic celebration the homily points to the presence of God in people’s lives and then leads a congregation into the Eucharist, providing, as it were, the motive for celebrating the Eucharist in this time and place.[2]

The role of the homily in leading the community to the thanksgiving of the Eucharistic Table is reiterated a few paragraphs later: “The function of the Eucharistic homily is to enable people to lift up their hearts, to praise and thank the Lord for his presence in their lives.”[3] Moreover, the document spoke of an “integral relation of the homily to the liturgy of the Eucharist,” indicating that the homily “should flow quite naturally out of the readings and into the liturgical action that follows.”[4] The authors warned against practices which could seem to weaken the connection between the homiletic moment and the liturgy.

|

| Photo: Freaktography; CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. |

Fulfilled in Your Hearing also gave strong emphasis to the rootedness of the homily in the Scripture readings assigned for the day. Yet the document framed the preacher’s task not so much as one of preaching “on” the readings, making the texts the homiletic focus in themselves, but rather preaching “from and through” the Scriptures in order to “interpret people’s lives in such a way that they will be able to celebrate Eucharist.”[5] The distinction in play here is a fine but crucial one, and often lost in actual practice. Yet Fulfilled leaves the preacher with a challenge to go beyond scriptural commentary and bring the scriptural perspective into dialogue with contemporary life.

Some commentators have complained that Fulfilled relies too exclusively on the Scripture readings as the point of contact between the homily and the liturgy, neglecting the other words and actions of the liturgy, the seasonal calendar, and the feast of the day as possible sources themselves for liturgical preaching.[6] These authors believe that the rich patristic tradition of mystagogical preaching is at stake in their critique. Attention to the full liturgical context, they believe, contextualizes the homily more properly as part of the liturgical worship.

More recently Catholic attention is being drawn to liturgical preaching by another episcopal statement, Preaching the Mystery of Faith: The Sunday Homily (USCCB, 2013). Although the connection between preaching and worship is not a major feature of this statement, it does assert an “essential connection between Scripture, the homily, and the Eucharist.”[7] That connection, the bishops say, is “why virtually every homily preached during the liturgy should make some connection between the Scriptures just heard and the Eucharist about to be celebrated.”[8] Admitting that making this connection homiletically might be very brief, or even indirect, the document presses on to a more central concern of the bishops at this moment: the homily as a catechetical opportunity. The authors carefully distinguish the homily as a liturgical moment from ordinary catechetical occasions and theology classes, and yet they plead for homilists to be mindful of the Church’s rich doctrinal tradition as they prepare for preaching in the Sunday assembly. “A wedge should not be driven,” they say, “between the proper content and style of the Sunday homily and the teaching of the Church’s doctrine.” This can be done in a way that respects the dynamics of the liturgy and is not “pedantic, overly abstract, or theoretical.”[9]

Ongoing Issues and Concerns

The foregoing historical sketch suffices to recount the advances in official teaching over the past five decades. Again and again the Catholic Church has gone on record asserting the importance of the Word, including preaching, precisely as an integral part of the community’s worship. But questions remain, and I choose two of these for brief examination here.

1. Questions of Meaning and Practice

As strongly as the documents propose the character of the homily as integral to worship, the exact meaning of this assertion is never made very precise. How ought the context of liturgy shape the type, style, method and/or substance of preaching? Worship has some salient characteristics. Three come readily to mind:

- the expression of praise to God, based on God’s own Being, power, authorship of life, and relationship with creatures;

- the expression of thanks to God for benefits received in an entire history of salvation;

- intercession to God, whereby worshipers implore God’s continued mercy and assistance.

How should the homily evince these characteristics? One might well envision words of praise, thanksgiving, and supplication issuing from the mouth of the preacher in the course of a Sunday homily. I have the impression that in some communities, especially in the African American tradition, preachers regularly engage in these modes explicitly. But, as communication within the context of a community between speaker and hearer, the homily has other purposes as well. More likely the intent behind the official Catholic documents is for the homily to evoke and inspire the assembly’s own praise, thanksgiving, and petition. The homilist’s role would then be, in part, to give voice to the assembly, but also to speak in such a way that the mysteries of God’s graciousness and goodness are laid bare and made available, as it were, for the transformation of human beings, who respond with worshipful adoration, gratitude, and supplication. However, absent some clear additional guidance, one might fear that preaching would be tempted to settle for lesser aims, e.g., mere moralism or superficial commentary on contemporary life or current events.

How is the homily as a participation in worship to be squared with the strong recent official emphases on catechetical instruction as part of preaching?

The message about the necessity and importance of preaching at the liturgy seems to have been received widely. Very rarely these days does one hear that a Catholic priest omitted the homily altogether at a Sunday Mass, nor at funerals, weddings, special feast days, and other celebrations. Even daily Masses most often include some brief preaching. So the official teaching of the Church has “succeeded” in restoring the homily to prominence in the context of the liturgy. But is the mere occurrence of preaching in the context of worship all that was envisioned by the Church’s teaching? I don’t think so. And it is rare that I hear reports of preaching that has a truly liturgical flavor, e.g., pointing explicitly to the Table of the Eucharist as Preaching the Mystery of Faith urged, or inviting a response of praise and thanks, or charging the faithful to continue the celebration and worship of God in their daily lives. How, exactly, is the homily to be an integral part of worship?

Moreover, how is the homily as a participation in worship to be squared with the strong recent official emphases on catechetical instruction as part of preaching? I do not say this cannot be done, but I think many preachers experience an inherent tension in negotiating both demands. Can “doctrinal preaching” still be worshipful preaching? If so, what does that look like, and how do we teach it?

2. Preaching on the Liturgy Itself

Without question, scriptural preaching has flourished in the Catholic community since Vatican II. Most Catholic clergy seem to have received the message that they are to “expound the word of God” (PO §4) when they get in the pulpit. But how many go beyond that, to pursue a “scriptural interpretation of human existence”[10] as the goal of their preaching? More to the point, how many Catholic homilies take the entire liturgy, and not merely the Scripture readings of the day, as “text” for preaching? The matter has been controverted in recent years. On the one side stand those who believe that the recovery of biblical preaching is one of the great achievements of the Council and the postconciliar period. Scriptural preaching, they believe, encourages more reading of the Bible and deeper love for the Bible among the faithful. Scripture-centered preaching is also more ecumenically advantageous, since scriptural preaching is the norm and assumption in most other Christian churches. On the other side stand liturgical theologians who argue strongly that the ministry of the Word must be firmly embedded within the liturgy—Scripture scholars who see the interpretation of the Word as the function of the whole Church, and patristic scholars who defend the vitality of the tradition of mystagogical preaching. For these thinkers, while the Scriptures hold pride of place, the entire liturgy speaks to the divine presence and action in the world, and thus all aspects of word, gesture, action, and element must be affirmed as possible raw materials for the preacher.

A leading voice of this latter camp has been Catholic liturgical theologian Edward Foley, O.F.M. Cap. In a thought-provoking article on this issue, Foley argues that “preaching without Scripture” is not a theological impossibility.[11] He notes that the “sacred text” mentioned in Sacrosanctum Concilium §52 really includes the whole of the liturgy, as has been clarified repeatedly in official documents over the years since then. For instance, in a 2003 statement, the U.S. bishops instruct that “the mysteries of faith and the guiding principles of Christian living are expounded most often from the Scriptures proclaimed but also from other texts and rites of the liturgy.”[12] Foley adds, “It is appropriate to preach not only about the eucharistic prayers and orations, but also about the central ritual actions, like the act of receiving Communion, the setting of the table or the act of being sent at the end of Mass.”[13] If we do not see the whole liturgy as the grounding of the homily, the author claims, we run three serious risks.

One is the risk of compromising what Fritz West called the “Catholic principle” in liturgy, i.e., that “the liturgy determines the readings,” not the other way around.[14] Foley notes the special readings assigned for the rites of initiation, funerals, and weddings. A second risk is that “too narrow a focus on the Scriptures puts at risk a homilist’s ability to ‘preach the moment’ for an assembly, deploying the full range of the liturgy’s power to take into account what the General Instruction calls ‘needs proper to the listeners.’”[15] Preaching in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, for example, had to be nimble enough to address the crisis on everyone’s mind at that moment. Thirdly, Foley claims that preaching from “an exclusively scriptural foundation” jeopardizes the “power of the Catholic imagination.”[16] The incarnational power of the Catholic sacramental imagination requires “preaching that proclaims the whole liturgy” and not merely the scriptural texts.

One of the most important developments in the Church since the Second Vatican Council has been the promulgation of the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults.[17] No doubt the full implementation of the RCIA is a decades-long process, but its influence is already changing parish life in many quarters. Parish liturgies today are much more frequently punctuated with the various rites of the initiation process—the Rite of Acceptance into the Catechumenate, the Rite of Election, the Scrutinies, the revived Easter Vigil, etc.—and these liturgical moments invite, almost demand, that the preacher help the liturgical community to unpack their full meaning and import.[18] I myself might well have remained in the former camp mentioned above, had I not been influenced profoundly by my experience in initiation ministry. But the Church still needs deeper ongoing reflection on how to do liturgical preaching that attends to the entire liturgical context, while still respecting the privileged place the Scriptures rightly hold in our community.

Looking for Ways Forward

Many things have been proposed to remedy the ills of Catholic preaching today. But, in terms of the issues at hand, I focus on just two broad suggestions.

-

Mystagogical preaching must be revived, cultivated, and taught.

|

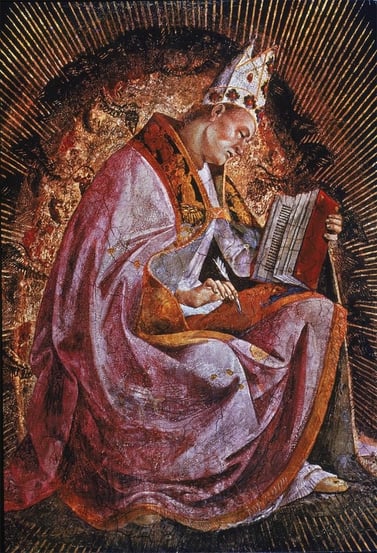

| Luca Signorelli; Saint Ambrose, Doctor of the Church (15th c.); Courtesy of ARTstor Slide Gallery (University of California, San Diego) |

The Church has a deep and rich tradition of preaching in a mystagogical vein, especially in the patristic era. Indeed much of the theological heritage of the first centuries of Christianity comes to us in the form of liturgical preaching, and quite often that preaching takes the form of reflection on the sacred rites. While it is certainly true that we cannot uncritically import methods and styles used in another time and place, however venerable, into our own, neither should we dismiss them out of hand. Often the mystagogical character of early Christian preaching simply reveals that the liturgy was the central axis of life for the community, and that the liturgy was experienced as a unity of praise and thanksgiving to the God of Jesus Christ.

Perhaps today we shy away from patristic preaching because of what we perceive to be its overuse of typological interpretation of Scripture. At times the heavy resort to allegorical meanings in patristic writings may obscure for us the simple and direct method involved in a mystagogical reflection on the experience of the liturgy, and these should not be confused. For example, the recent work of Craig Satterlee on the mystagogical preaching of Ambrose[19] makes clear that patristic preaching could be sophisticated, powerful, and holistic in appeal. Homileticians need to partner with early Church scholars to continue to plumb the depths of the early Fathers, for whom any distance between theology and liturgy, and any “split between preaching and liturgy”[20] was practically unknown.

Teachers of homiletics also need to work collaboratively with liturgical theologians to explore the understanding of preaching as an act of worship more deeply. The situation ‘on the ground’ is already slowly changing as the implementation of the RCIA becomes more widespread. But there are few resources available to help the preacher who wants to forge connections between his ministry of the Word and the initiation rites, or even the Eucharist itself.

Homileticians need to partner with early Church scholars to continue to plumb the depths of the early Fathers.

Official encouragement of a more mystagogical style of preaching would also help to bridge the perceived gaps between doctrine and Scripture, and between preaching and catechesis. The mystagogical style is able to carry doctrinal freight, as it were, while still maintaining the proper character of the homily as both liturgical and evangelical. In short, mystagogical preaching offers us the possibility of an approach that is more theologically and anthropologically integrated.

Homileticians will need to reconsider their pedagogy to include the mystagogical element, which is generally neglected now in the homiletics curriculum of formation programs. Models and methods of creating effective mystagogical homilies need to be developed and shared in the Catholic homiletics community. A contemporary mystagogical style, sensitive to the full range of pastoral demands made upon the Sunday homily, needs to be developed.

-

The theology of the sacramentality of the Word needs further development.

Both the importance of preaching and the liturgical contextualization of preaching rest on an understanding of the divine presence in liturgical action. The fourfold character of that presence advanced in Sacrosanctum Concilium §7 remains the key theological foundation of this discussion. One way in which this discussion has advanced is through the notion of the sacramental character of the Word of God, an expression which has surfaced with increasing frequency in Catholic theological literature. Mary Catherine Hilkert had appealed to the “sacramental imagination” in her understanding of the Word as far back as 1997.[21] But the phrase “sacramentality of the Word” first came to my attention through the work of Paul Janowiak, who turned to Semmelroth, Rahner, and Schillebeeckx to lay the foundations for a sacramental understanding of the divine presence in the Word.[22]

More recently the theme was taken up at the 2008 Synod of Bishops on “The Word of God in the Life and Mission of the Church,” and thence in Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s post- synodal apostolic exhortation Verbum Domini (2010). In a major section entitled “The Liturgy, Privileged Setting for the Word of God,” Benedict XVI affirms “the profound unity of word and Eucharist . . . grounded in the witness of Scripture (cf. Jn 6; Lk 24), attested by the Fathers of the Church, and reaffirmed by the Second Vatican Council” (Verbum Domini, §54).[23] He continues, “Word and Eucharist are so deeply bound together that we cannot understand one without the other: the word of God sacramentally takes flesh in the event of the Eucharist” (VD §55). Turning directly then to the Synod’s affirmation of the sacramentality of the Word, Benedict XVI first recalled that his predecessor John Paul II had spoken of the “sacramental character of revelation” (VD §55).[24] He then draws an analogy with the understanding of Christ’s “real presence” under the forms of consecrated bread and wine. Inviting further reflection and study, the Pope concluded:

A deeper understanding of the sacramentality of God’s word can thus lead us to a more unified understanding of the mystery of revelation, which takes place through “deeds and words intimately connected”; an appreciation of this can only benefit the spiritual life of the faithful and the Church’s pastoral activity. (VD §56; citing Dei Verbum, §2)

But all of this is little more than a promising beginning of a theological trajectory. To speak of the “sacramentality” of the Word of God does seem to capture something the Christian faithful already know experientially, viz., that the proclaimed and preached Word does actually convey the gracious, relational divine presence of which it speaks. One recent writer calls this “the astonished confession that preaching participates in the very thing which gives rise to our worship and life as church: God’s self-giving in life, word and sacrament.”[25] Janowiak proposed that the development of this theme of reflection would offer multiple avenues for ecumenical dialogue, especially with the thought of both Luther and Calvin.[26]

Yet a fuller account of that sacramental presence in the Word needs to be given. There is need for a more expansive view of the ways in which ministers of the Word (both liturgical readers and preachers) helpfully collaborate with the Holy Spirit so that that presence can be experienced by the assembly, responding in faith. As both the Synod and Pope Benedict XVI saw, the full development of this topic could have far-reaching, positive implications for both the quality of Catholic preaching and its linkage to the liturgy.

Conclusion

As the Catholic community celebrates the 50th anniversary of Sacrosanctum Concilium, we can be thankful for the myriad ways in which devotion to the Word of God has been renewed and nurtured among us. Preaching has been restored to its rightful place of prominence in the structure of the liturgy. Catholic homileticians have joined the ecumenical conversations around the understanding and practice of good preaching. The Catholic faithful have begun to expect and seek out good preaching as part of regular worship. Catholic preachers, nourished by the theological renewal of these years, can attest as well that preaching can indeed be “difficult conversation.” As Pope Francis said in a recent homily, “The riches and cares of the world choke the Word of God and do not allow it to grow.”[27] But many are the Catholic preachers who will also attest that preaching can be an exciting, life-giving, and mysterious endeavor, an adventure into the salvific presence of God in Jesus Christ. As Pope Francis said on another recent occasion:

We must always have the courage and the joy of proposing, with respect, an encounter with Christ, and being heralds of his Gospel. Jesus came amongst us to show us the way of salvation and he entrusted to us the mission to make it known to all to the ends of the earth. . . . It is urgent in our time to announce and witness to the goodness of the Gospel.[28]

![]()

Editors’ Note: This essay originally appeared in Church Life: A Journal for the New Evangelization, volume 2, issue 3.

Featured Photo: Catholic Diocese of Saginaw; CC BY-ND 2.0.

[1] See William Skudlarek, The Word in Worship: Preaching in a Liturgical Context (Abingdon, 1981), 65.

[2] Bishops’ Committee on Priestly Life and Ministry, U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Homily in the Sunday Assembly (U.S. Catholic Conference, 1982), 23. The interior quote in the first line is not footnoted, but is apparently from Sacrosanctum Concilium, §52, above. The paragraph is footnoted to the English translation of the Second Editio Typica of the Lectionary for Mass (1981).

[3] Ibid., 25.

[4] Ibid., 23.

[5] Ibid., 20.

[6] See Edward Foley, O.F.M. Cap., Guerric DeBona, O.S.B., and Mary Margaret Pazdan, O.P., “III. The Homily,” in James A. Wallace, ed., Preaching in the Sunday Assembly: A Pastoral Commentary on Fulfilled in Your Hearing (Liturgical Press, 2010), 35.

[7] USCCB, Preaching the Mystery of Faith (2013), 20.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 24.

[10] Fulfilled in Your Hearing, 29.

[11] Edward Foley, O.F.M. Cap. “Scripture Alone? Rethinking the Homily as a Liturgical Act” in America (May 25, 2009), 10–13. See also Samuel Torvend, O.P., “Preaching the Liturgy: A Social Mystagogy” in Regina Siegfried and Edward Ruane, eds., In the Company of Preachers (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1993), 48–65.

[12] USCCB, Introduction to the Order of Mass (2003), §92.

[13] Foley, 12.

[14] Ibid.; see also Fritz West, Scripture and Memory (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1997), 47–52.

[15] Foley, 13.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Following an experimental period, the document’s final promulgation in the United States occurred in 1988.

[18] See, for example, J. Michael Joncas, Preaching the Rites of Initiation (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 1994).

[19] Craig A. Satterlee, Ambrose of Milan’s Method of Mystagogical Preaching (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2002).

[20] Skudlarek, 74f.

[21] M. C. Hilkert, Naming Grace: Preaching and the Sacramental Imagination (New York: Continuum, 1997).

[22] Paul Janowiak, The Holy Preaching: The Sacramentality of the Word in the Liturgical Assembly (Collegeville, Liturgical Press, 2000). See also his Standing Together in the Community of God: Liturgical Spirituality and the Presence of Christ (Collegeville, Liturgical Press, 2011), esp. Chap. 3, “‘The Book of Life in Whom We Read God’: The Presence of Christ in the Proclamation of the Word.”

[23] In a footnote to this line Benedict references several documents, including Sacrosanctum Concilium, §§48, 51, and 56; Dei Verbum, §§21 and 26; Ad Gentes, §§6 and 15; and Presbyterorum Ordinis, §18.

[24] Benedict XVI cites John Paul II’s encyclical Fides et Ratio (1998), §13.

[25] Todd Townshend, The Sacramentality of Preaching: Homiletical Uses of Louis-Marie Chauvet’s Theology of Sacramentality (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2009), 1.

[26] Janowiak, The Holy Preaching, 178–83.

[27] Pope Francis, Homily at Casa Santa Marta (June 22, 2013).

[28] Pope Francis, Message for World Mission Day (May 19, 2013), §3.