It is well known that the reforms of the liturgy associated with Vatican II had as their goal greater participation on the part of all. Many things changed in the external celebration of the rites designed to facilitate this, and those changes have borne abundant fruit. But the renewal of the liturgy also wished to provide a fresh understanding of the meaning of the rites, a deeper theological grasp of what the words and the signs mean. And ultimately of what God does, what God accomplishes when the sacred liturgy is celebrated. Deepening this theological grasp is of immediate pastoral relevance, for it means greater interior and conscious participation in the rites themselves. This theological renewal is a work that we can take up anew, a question that continually needs our attention.

This is the approach that The Catechism of the Catholic Church takes, and here I would like to show how useful some of its formulations are for a deepened understanding of the liturgy. After ten brief paragraphs that deal with preliminaries (CCC §§1066-1075), the first major section on the liturgy (CCC §1076) begins with an immensely profitable paragraph for those seeking to develop a fuller, more conscious, and active participation in liturgical prayer. I want to comment on this paragraph here.

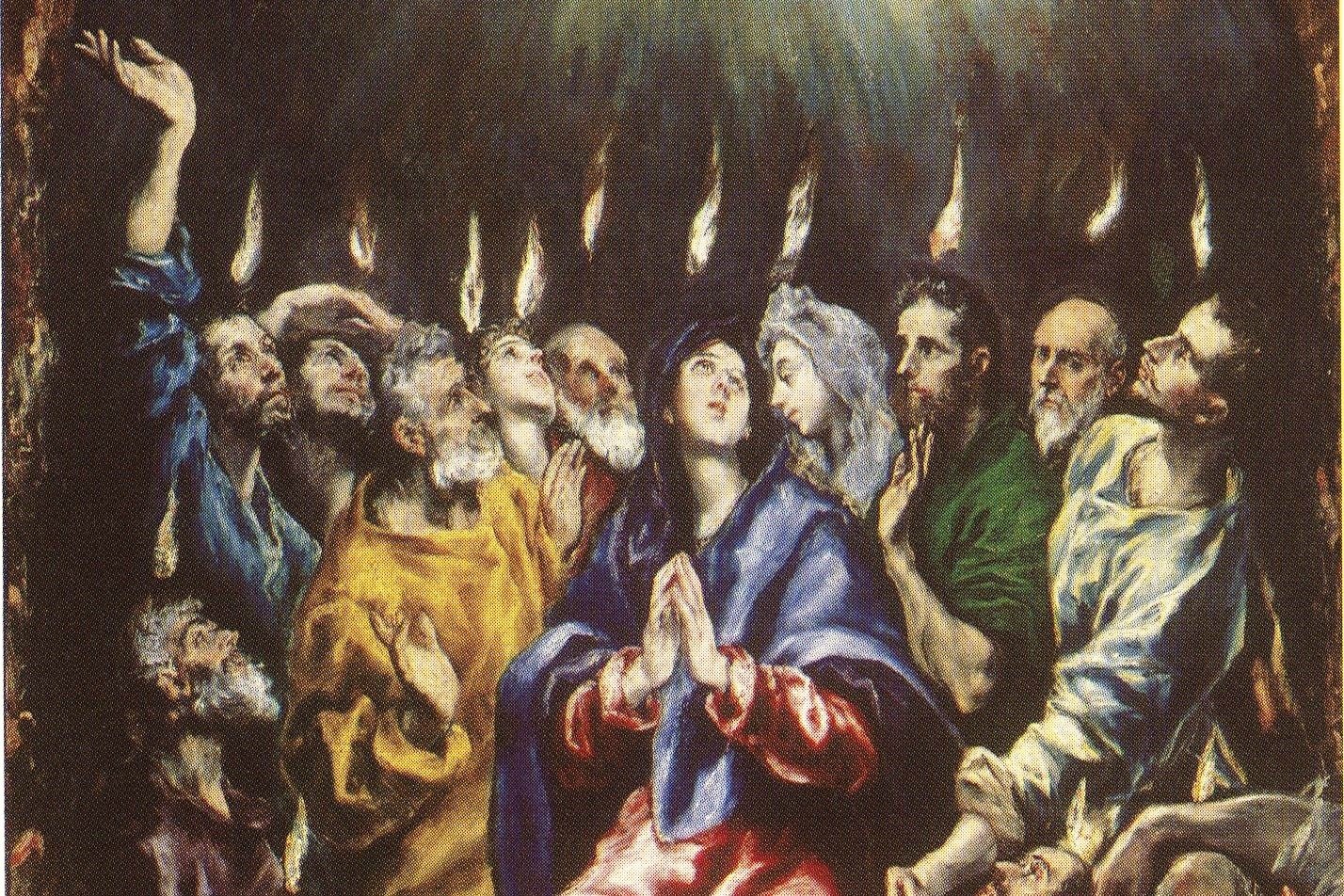

Strikingly, the section begins with the mystery of Pentecost. “The Church was made manifest to the world on the day of Pentecost by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.” The significance of such a beginning should not be missed. Pentecost is the culmination of Jesus’ Paschal mystery, where the crucified and now risen and ascended Lord lavishes on the world the Spirit with which he himself was anointed. We could say that Pentecost is the point at which Jesus wished to arrive, as it were, so that what he did in one time and place could be extended to every time and place through his Holy Spirit. This extension is the Church, that is, the assembly of all that Jesus draws to himself when he is lifted up. (See Jn 12:32).

After Pentecost, Jesus is active in a new way through his Spirit: “The gift of the Spirit ushers in a new era in the ‘dispensation of the mystery’— the age of the Church…” The expression “new era” is especially helpful, for it indicates that our communion with Christ and conformity to him will not come about through some imaginative leap backwards in time. We are not trying to picture ourselves encountering a first-century Jewish rabbi. No, this new era is a realm appropriate to the new condition; namely, his glorification at the right hand of his Father. This new era is “the age of the Church, during which Christ manifests, makes present, and communicates his work of salvation through the liturgy of his Church, ‘until he comes.’”

So this is where and how and why the liturgy appears. Jesus, having lived the particular circumstances of a single earthly existence that culminated in his crucifixion, is now glorified and will come again in glory. Between the one coming and other, as the many centuries pass, Christ is constantly doing three things through the liturgy. He is manifesting and making present and communicating to every time and place his work of salvation accomplished in one time and place.

These three actions are consequential for our active participation in the liturgy. They describe what we are to discern and grasp. They are a clue to the meaning of all the words and gestures and signs. In fact, among everything that happens in the liturgy, it is nothing less than Christ himself at work. Through the liturgy’s words, gestures, and signs, the mighty deed of Christ’s death and resurrection is displayed before us (Christ manifests) as the very content of liturgy. By means of words, gestures, and signs the past event becomes a present event (Christ makes present). Through them all, the power of the saving deed is delivered to us in such a way that we are saved by it (Christ communicates).

But why is it that this should happen through the liturgy? “In this age of the Church Christ now lives and acts in and with his Church, in a new way appropriate to this new age.” In fact, liturgy is a consequence of Jesus’ glorification, and it is “appropriate” precisely because the realm of words, gestures, and signs pulls us into the domain of faith, without which we could not detect his presence as risen Lord. For “risen” does not mean that Jesus is simply “up and running again” and so has returned to the ordinary human existence that he shared with us before his Paschal Mystery. If that were all it meant, then one would have to—I can only speak somewhat facetiously—go to Jerusalem and stand in a long line waiting to meet Jesus. But no. “Risen” means filled with divine glory. “Risen” means a body once crucified now placed in a realm entirely beyond death. “Risen” means present in the Spirit, filling all material things with a sacramental presence in which matter is used to communicate this new life, yet never in such a way that the fullness of this life is available here and now. This is the “new way appropriate to this new age.”

Two thousand years between us and the historical Jesus is not a gap when the Spirit is “the Church’s living memory.”

“He acts through the sacraments in what the common Tradition of the East and the West calls ‘the sacramental economy’” “Economy” here means a divine arrangement of things; in this case, God’s own arrangement that the life of the risen Lord should be delivered to the Church through the sacraments, that is, through the material elements of the liturgy. The next part of the sentence says it this way: “this is the communication (or ‘dispensation’) of the fruits of Christ’s Paschal mystery in the celebration of the Church’s ‘sacramental’ liturgy.” The fruits of Christ’s Paschal mystery— his death, resurrection, ascension, and sending of the Spirit are all for our sake. All this is communicated to us, “dispensed” to us, in the celebration of the liturgy. The fruit of Christ’s Paschal mystery is the Church herself, which comes into being as the fruits are communicated through the words, signs, and gestures of the liturgy.

Rightly then, we must attend to the external forms of the liturgy and enact them well. The ultimate reason for this is not in order to pull off some event, which in virtue of the force of its performance, moves the participants, pleases them, and stirs them up. Rather, these external forms are a divine economy through which Christ manifests himself as present and acting to save us. Every time the liturgy is celebrated, Jesus, in effect, is present to the assembly saying, “I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate to be with you always, the Spirit of truth, which the world cannot accept, because it neither sees nor knows him. But you know him because he remains with you and will be in you.” (Jn 14:16-17).

The Father: Source and Goal of the Liturgy

Thus far I have spoken of just one section of the Catechism, §1076, which offers a dense but accessible theological opening to the nature of the liturgy. This paragraph is followed by a section on the Father as source and goal of the liturgy. Sections 1077 to 1112 are a beautiful treatment of how the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are all at work in the Church’s liturgy, each in a different but profoundly related way. The section is divided into smaller parts which treat in turn the roles of each member of the Trinity, beginning with the Father. I will comment now on the paragraphs that concern the Father (§§1077-1083), leaving the other sections for later columns. In all that I say about these paragraphs, I try to unfold the riches that are packed into the various formulations. It is my hope that, once having followed the commentary, my reader will find that the words of the Catechism thereafter stand forth in all their strength. And then one could refer back to the Catechism—and not this essay!—to recall and deepen the grasp on the very rich thinking of the Church expressed there.

One of the stylistic features of the Catechism that I particularly appreciate is how it very often just “talks Scripture,” that is, it embeds scriptural verses seamlessly into its discourse and makes these verses part of the whole. This is routinely done without a particular introduction that would begin something like, “As St. Paul [or somebody else] says…” This has the effect of saturating the catechetical text with Scripture and at the same time rendering the teaching in the form of a deepened grasp of Scripture or of its further unfolding. This Scriptural discourse is the style employed to open this section on the Father. Without saying so, the text begins with the beautiful hymn of praise that St. Paul uses to open his letter to the Ephesians. “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places” (CCC §1077). The biblical text is well-suited to begin a development on the Trinity, for it mentions “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” and further says that it is he who is blessing us in Christ. (The Spirit will be mentioned shortly after; it is normal in Trinitarian talk to begin with Father and Son.) But the biblical text is likewise chosen because the Catechism wants to focus on the words blessed and blessing and to use the concept of blessing to describe liturgy.

The notion of blessing moves in two directions (CCC §1078). It describes what God has done and continues to do for us, but it also describes what we do in response to God’s blessing. We bless God, as the language of the psalter teaches us often to do, as in “Bless the Lord, O my soul!” or “I will bless the Lord at all times!” or many such similar expressions. With this twofold direction of blessing established, the Catechism can then make a very large statement: “From the beginning until the end of time the whole of God’s work is a blessing” (CCC §1079). It should be noticed that the Catechism’s language is not explicitly about liturgy yet. This approach wants to put liturgy into a larger category, a category as big as God’s whole dealing with his creation from the beginning to the end of time.

This thought is developed in the several sentences and paragraphs that follow. This huge sweep of “from the beginning to the end of time” is displayed in the way we know it from the Bible. The creation itself is a blessing, “especially man and woman.” The peace established after the flood with Noah is mentioned and the qualitative shift in blessing that begins with Abraham (CCC §1080). Then an impressive list of blessings is unfolded, and the Catechism’s language becomes an eloquent echo and summary of the major epochs of blessing that the Bible narrates:

The divine blessings were made manifest in astonishing and saving events: the birth of Isaac, the escape from Egypt (Passover and Exodus), the gift of the promised land, the election of David, the presence of God in the Temple, the purifying exile, and return of a ‘small remnant.’ The Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms, interwoven in the liturgy of the Chosen People, recall these divine blessings and at the same time respond to them with blessings of praise and thanksgiving. (CCC §1081)

This long list successfully impresses upon us how varied and abundant the blessings of God have been. It is indeed “astonishing.”

At the end of the paragraph just cited, liturgy is at last explicitly mentioned, “the liturgy of the Chosen People.” The twofold direction of blessing is recalled again because repetition is good teaching, and the point is more concrete now because of the preceding long list. The shape of liturgy is emerging out of the huge sweep of blessings mentioned: liturgy “recall[s] these divine blessings and at the same time respond[s] to them with blessings of praise and thanksgiving.”

The next paragraph follows quite naturally from this, but at the same time it marks a significant qualitative shift. Carefully constructing this rich context of blessing from the beginning of creation and through the history of the Chosen People, the Church can now express in a very direct statement her belief about her own liturgy: “In the Church’s liturgy the divine blessing is fully revealed and communicated” (CCC §1082). A great deal is claimed in this simple sentence.

In the context of the vast history of divine blessing (a history as old-as-the-world), the Catechism zeroes in on a particular context: the Church’s liturgy. And about this liturgy, two things are claimed. First, in the Church’s liturgy, divine blessing is fully revealed. Second, the blessing is not only revealed, it is also communicated. We should pause to be sure we have grasped the enormity and wonder of this claim. We should recall it every time we celebrate the liturgy. The short sentence needs development, of course. In the sentences that follow, the development is explicitly Trinitarian in its formulation. Likewise, the notion of blessing continues to be the leitmotif of all that is said. So, developing this thought, it can be said that the divine blessing is fully revealed and communicated in the Church’s liturgy because, “the Father is acknowledged and adored as the source and the end of all the blessings of creation and salvation.”

|

| Alek Rapoport, Trinity in Dark Tones (Genesis 18) (1994); CC-BY-SA-3.0. |

This is a first dimension of liturgy: we acknowledge the Father as the source and end of blessing, and we adore him. We bless him for blessing us. But what is the climax of the Father’s action of blessing? The next sentence says it: “In his Word who became incarnate, died, and rose for us, he fills us with his blessings.” In terms of Trinitarian theology this sentence is carefully constructed. The second Person of the Trinity is acting in his Incarnation, Death and Resurrection, but he is named as the Father’s Word in whom the Father fills us with his blessing. We are in the heart of the Trinitarian mystery here. The Father is the source of another, “his Word,” through whom he acts, through whom he blesses.

This concentrated presence and action of the Father’s Word, Jesus Christ, is a second dimension of liturgy. The next sentence continues the development of this display of the mystery of the Trinity and gives us a third dimension of the liturgy: “Through his Word, he pours into our hearts the Gift that contains all gifts, the Holy Spirit.” Theologically this is a perfectly balanced sentence and a profound thought. The Father remains the subject; he acts through his Word; and through that Word he gives us the greatest blessing of all: the Holy Spirit. If one were to say, “Show me all that!” then we could point to the liturgy and say, “In the Church’s liturgy the divine blessing is fully revealed and communicated.”

The final paragraph of this section of the Catechism on the Father as the source and goal of all liturgy is an even more tightly packed Trinitarian formulation. The paragraph gathers into several statements all the rich ideas laid out in what has preceded. The twofold direction of Blessing remains essential to follow this paragraph’s sense. The liturgy is called “a response of faith and love to the spiritual blessings the Father bestows on us.” (CCC §1083). The two directions are both there: the Father’s blessings and our response. But our response is described in an elaborate sentence that names the Church in the liturgy and each of the members of the Trinity in different positions:

The Church never ceases to present to the Father the offering of his own gifts and to beg him to send the Holy Spirit upon that offering, upon herself, upon the faithful, and upon the whole world, so that through communion in the death and resurrection of Christ the Priest, and by the power of the Spirit, these divine blessings will bring forth the fruits of life ‘to the praise of his glorious grace.’

We have come full circle from the citation of St. Paul that opened this section. In the liturgy we are exclaiming, “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places.” A phrase from the full citation of the Pauline text is used again now to finish this section and to indicate that this paragraph concludes the development. Both directions of blessing are there. The Church prays that the divine blessings will bring forth the fruits of “the praise of his glorious grace.” The praise of his glorious grace—this indeed is an excellent way to say what we are doing when we celebrate liturgy.

Christ's Work in the Liturgy

In the Catechism of the Catholic Church paragraphs 1077 to 1112 are a beautiful treatment of how the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are all at work in the Church’s liturgy, each in a different but profoundly related way. The section is divided into smaller parts which treat in turn the roles of each member of the Trinity, beginning with the Father. I commented above on those parts that concerned the Father. In this present section I would like to treat the paragraphs titled “Christ’s Work in the Liturgy,” paragraphs 1084 to 1090.

Titles and subtitles are effectively used throughout the Catechism. They help the reader to see the structure and logic of the exposure. The subtitles of this section on Christ’s role in the liturgy have subtly employed a useful technique of putting three periods either before or after the four subtitles, indicating that the four sections can form one sentence. So, “Christ glorified…” is the first section, while the second section is titled “from the time of the Church of the Apostles…” Then, “is present in the earthly liturgy” and finally, “which participates in the liturgy of heaven.” Seven dense paragraphs can thus all be summarized with one sentence: Christ glorified, from the time of the Church of the Apostles, is present in the earthly liturgy, which participates in the liturgy of heaven. Let us see how the Catechism exposes all that is contained in this loaded sentence.

It is good to recall that we are in a part of a larger section titled “The Liturgy— Work of the Holy Trinity.” Even as the exposition naturally treats Father, Son, and Spirit in that traditional order, it regularly links one member of the Trinity to the others. This is done effectively in the first subsection titled “Christ glorified…” The very first statement includes mention of all three persons of the Trinity in a dynamic relationship to each other, acting for the sake of the Church. The emphasis falls on Christ, the focus of this section. It says, “’Seated at the right hand of the Father’ and pouring out the Holy Spirit on his Body which is the Church, Christ now acts through the sacraments he instituted to communicate his grace” [emphasis mine] (§1084). So, Christ is the principle one who acts in the liturgy, but he does this from the “place” of his glorification, expressed here in the biblical phrase, “seated at the right hand of the Father.” From there he pours out the Holy Spirit on the Church. Ascension and Pentecost stand behind this formulation, an idea previously established in §1076 and upon which I commented above. In the Ascension, Christ is taken from our sight but only to act in a new and deeper way through the Holy Spirit in the liturgy.

There follows a definition of sacraments, which older Catholics will recognize as a slight expansion on a traditionally pithy and efficient way of saying what sacraments are. “The sacraments are perceptible signs (words and actions) accessible to our human nature. By the action of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit they make present efficaciously the grace that they signify” (§ 1084). The older and simpler definition that I remember from my youth was “Sacraments are outward signs instituted by Christ to give grace.” The slightly longer definition of the Catechism adds several dimensions to this essential core. It specifies “words and actions” as what the signs are formed of.

This rightly draws our attention to both as requiring our understanding. It further emphasizes that these signs are fitted to the perception of our human nature— a useful reminder; for after all, it is God who is acting and it is good to take note that he acts in a manner suited to us and our way of understanding. Another addition to the older simpler core is mention of the Holy Spirit along with Christ. This addendum allows for a fuller Trinitarian understanding of sacraments and will be developed in the next major section on the Holy Spirit and the liturgy.

The next paragraph, §1085, says precisely what that grace is. This paragraph is one of the densest and most beautifully formulated paragraphs of the entire Catechism. It is packed with theology, and, once understood in its fullness, it serves as a very useful formulation of what this section sets out to teach; namely, “Christ’s Work in the Liturgy.” Picking up on the words “make present” and “signify” from the definition of sacraments just given, this paragraph begins with a short sentence that says it all, even if it will need to be unfolded in what follows: “In the liturgy of the Church, it is principally his own Paschal mystery that Christ signifies and makes present.” So, the Paschal mystery is the basic content. The words and actions of the liturgy deliver that— or better said, the action of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit deliver that.

Then the phrase “Paschal mystery” is developed. Even without the Catechism it is, of course, known that this phrase basically refers to the death and resurrection of Jesus; but several things are quite useful in the way the Catechism sets forth this teaching. It first notes that Jesus pointed to this climax of his mission throughout his earthly life both by his teaching and his actions. But the passage then comes quickly to the center and does so by using an expression of Jesus that we know from John’s Gospel, even if that origin is not explicitly noted here. In John’s Gospel Jesus spoke of his approaching death and resurrection as being “his hour.” At the turning point of the whole gospel we read, “Before the feast of the Passover, Jesus knew that his hour had come to pass from this world to the Father” (Jn 13: 1). Relying on this and other uses of the term from John’s Gospel, the Catechism says, “When his Hour comes, he lives out the unique event of history which does not pass away: Jesus dies, is buried, rises from the dead, and is seated at the right hand of the Father ‘once for all.’” All this is the Paschal mystery, and it is this that Christ signifies and makes present by the words and actions of the liturgy. He can make present what happened in the past precisely because it is “his Hour,” which the Catechism strikingly notes “does not pass away.” It explains how this could be. Precisely because it is “his Hour,” it is unique in its relationship to time. “His Paschal mystery is a real event that occurred in our history, but it is unique: all other historical events happen once, and then they pass away, swallowed up in the past.”

That the Paschal mystery is a real event that occurred in history is a crucial point. Jesus really was crucified at one particular time and in one particular place. Indeed, in this way the Son of God shows that he really did become incarnate and enter into history, so deeply in solidarity with our condition that he enters the ultimate limits that death imposes on our particular time and place. Then from one particular place and time Jesus rises and is filled with divine glory. Resurrection bursts the bonds of time and place. “The Paschal mystery of Christ, by contrast, cannot remain only in the past, because by his death he destroyed death, and all that Christ is— all that he did and suffered for all men— participates in the divine eternity, and so transcends all times while being made present in them all.”

Jesus really was crucified at one particular time and in one particular place. . . . Then from one particular place and time Jesus rises and is filled with divine glory.

This is beautifully put: “transcends all times while being made present in them all.” To destroy death means, among other things, that the bonds of a particular time and place are burst open. Time and space themselves are burst open, and the risen and glorified Christ is present in them all. In the liturgy Christ signifies this (precisely this!) and makes it present. The paragraph ends with what is nothing less than a joyful announcement: “The event of the Cross and Resurrection abides and draws everything toward life.”

Clearly, this is a powerful formulation and teaching of “Christ’s Work in the Liturgy.” This is the first of four points developed around this theme, and it is the foundation of the others. The subsequent paragraphs in fact are for the most part simply citations from Vatican II’s programmatic document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. This too is a common feature of the Catechism’s style of teaching. It cites the documents of many councils but especially those of Vatican II. As such, it can be considered a kind of hermeneutic of the Council and indeed part of the task of its ongoing application. It is probably the case that, apart from theological experts, not many people actually sit down anymore and read Sacrosanctum Concilium straight through. But throughout the Catechism we encounter this document and other major documents cited again and again.

Here I have chosen to concentrate my attention on the several paragraphs of the Catechism that are newly formulated. These paragraphs form a new context for the conciliar citations, which in many other places have been usefully commented upon. The Catechism uses these citations to unfold the single sentence that I said at the beginning could summarize this whole section: Christ glorified, from the time of the Church of the Apostles, is present in the earthly liturgy, which participates in the liturgy of heaven. I have tried to show how enormous is the beginning of this sentence: “Christ glorified . . . .”

The Holy Spirit and the Church in the Liturgy

Above I commented on those parts of the Catechism of the Catholic Church that concern the distinct roles of the Father and the Son in the liturgy. Next I would like to begin to treat the section entitled “The Holy Spirit and the Church in the Liturgy” (§1091-1109).

It is striking that after considering the role in the liturgy of the Father in Himself and of Christ in Himself, these next paragraphs of the Catechism treat the Holy Spirit together with the Church. This is seen already in the title of the section, and the reasoning behind this is immediately explained: “The desire and work of the Spirit in the heart of the Church is that we may live from the life of the risen Christ” (§1091). The Spirit is, as it were, looking in two directions: toward the risen Christ and toward the Church. He “takes” from the risen Christ and makes what he takes the Church’s own. When the Spirit finds in us “the response of faith which he has aroused,” then the liturgy in fact can become “the common work of the Holy Spirit and the Church” (§1091). This is something marvelous. The liturgy is something that God does, and it is something that the Church does. It is at one and the same time a divine work and a human work.

A huge claim follows, even if it is expressed in deceptively simple language. It is that in the liturgy “the Holy Spirit acts in the same way as at other times in the economy of salvation” (§1092). This means that the divine action of the Spirit that unfolded through all the centuries of both the Old and the New Testaments is concentrated now in the event of the liturgy. Four verbs summarize the Spirit’s action: the Spirit prepares the Church to meet Christ, recalls Christ, makes present His mystery, and unites the Church to Him. Each of these dimensions is developed under separate subtitles. This whole section of the Catechism on the Holy Spirit and the Church in the liturgy is twice as long as the sections on the Father’s and the Son’s roles. For the present let us examine the first of the four subtitles.

The Holy Spirit prepares for the reception of Christ. This title, this sentence, exactly describes the action of the Spirit in two places: in the economy of salvation and in the sacramental economy. As such, it is the first instance of what I called a “huge claim,” namely, the convergence of Spirit’s work in salvation history with Spirit’s work in the liturgy. Throughout the Old Covenant, the Spirit was preparing a people for Christ’s coming. Now, in the liturgy, all that was prefigured there is fulfilled. This is why “the Church’s liturgy has retained certain elements of the worship of the Old Covenant” (§1093). Three such elements are mentioned, the first two stated simply as reading the Old Testament and praying the Psalms. The third element is more complex. It is “recalling the saving events and significant realities which have found their fulfillment in the mystery of Christ” (§1093).

Underlying this expression is the notion of feast as understood in the religion of Israel. Feasts consisted in “recalling saving events,” which, precisely because they were God’s deeds, could become present again in the celebration of their memory. These events cumulatively build up an inner meaning, which the Catechism calls “significant realities.” Key instances are mentioned: “promise and covenant, Exodus and Passover, kingdom and temple, exile and return” (§1093). All of these find their fulfillment in the mystery of Christ, and it is as we recall those events and realities in the liturgy that the Spirit fulfills them in our very midst.

|

| Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik; The Baptism of the Lord (2007), detail: Holy Spirit; Photo: Carolyn A. Pirtle. Used with permission. |

The next paragraph defends this concept, or in any case, gives it a firm theological foundation, calling the relation between what was prefigured in the Old Covenant and its fulfillment in Christ the “harmony of the two Testaments.” The Catechism affirms: “It is on this harmony of the two Testaments that the Paschal catechesis of the Lord is built, and then, that of the Apostles and the Fathers of the Church” (§1094). The term “Paschal catechesis” provides important insight into the Church’s justification of the way in which she understands the Old Testament and uses it in the liturgy. In reality, the Church’s understanding of the Old Testament is “Paschal catechesis,” and its original and authoritative practitioner is the risen Lord Himself.

A footnote in this paragraph refers the reader to Luke 24:13-49 where, in two different Resurrection appearances, the Lord indicates that the Messiah’s Death and Resurrection is the meaning of Moses and the prophets and the Psalms, of the entire Old Covenant. The Apostles, the Catechism contends, build their understanding of the mystery of Christ on His own “Paschal catechesis,” and the Church Fathers follow in the pattern of the Lord and the Apostles.

The Catechism states that this way of interpreting the hidden meaning of the letter of the Old Testament has a technical name: “It is called ‘typological’ because it reveals the newness of Christ on the basis of the ‘figures’ (types) which announce him in the deeds, words, and symbols of the first covenant” (§1094). That is, the warrant for this method of scriptural interpretation is in the Scriptures themselves, as the Catechism then demonstrates with examples from the New Testament. Typological interpretation of Scripture is not the invention or intrusion of a later period or a different culture — say, that of the patristic Church. No, the Fathers continued what was begun by the risen Lord and the Apostles, and they extended it to all parts of the Scriptures.

All of this explains why in her liturgy the Christian Church continues to celebrate the great deeds of God from Israel’s past. Just as the Holy Spirit was preparing Israel for the coming of Christ, now the same Spirit prepares the liturgical assembly for the coming of Christ. The Catechism puts forward the various liturgical seasons as prime examples of this: “For this reason the Church, especially during Advent and Lent and above all at the Easter Vigil, re-reads and re-lives the great events of salvation history in the ‘today’ of her liturgy” (§1095). All of us who hear these Old Testament readings proclaimed during Advent, Lent, and especially at the Easter Vigil, will certainly listen more sensitively and profit the more from hearing them if we keep in mind that by means of them the Holy Spirit is actively preparing us to meet Christ in the very liturgy in which they are proclaimed.

The phrase “above all at the Easter Vigil” deserves our attention. The Catechism does not develop it in this particular paragraph, but it does provided us with a crucial element of what is needed to understand more deeply this part of the “mother of all Vigils” (Missale Romanum, “Rubrics for the Easter Vigil,” §20). The Holy Spirit is active in the liturgical assembly precisely by means of the details of what is read. The seven Old Testament readings of the Easter Vigil are representative texts that proclaim whole blocks of essential Old Testament theology, moving from creation through Abraham’s sacrifice to the most important reading, the Exodus; four subsequent readings announce pivotal themes of the prophets.

An understanding of these texts in relation to the Paschal Mystery, which is so explicit in the Easter Vigil, can serve also when these or similar readings appear at other times in the liturgical year. The Collects that follow each reading are a rich resource for understanding these links between Old Testament themes and their fulfillment in Christ’s Paschal Mystery. These express with simplicity and clarity the Church’s profound Christological and sacramental understanding of the Old Testament texts.

This first subsection of the Catechism on the Holy Spirit and the Church in the liturgy concludes by returning to the word “prepare” from its title, highlighting again the notion of the liturgy as a common work of both the Holy Spirit and the Church. “The assembly should prepare itself to encounter its Lord and to become ‘a people well disposed.’ The preparation of hearts is the joint work of the Holy Spirit and the assembly, especially of its ministers” (§1098). We can hope that this work of the Holy Spirit in us, together with our own disposition to be open to his inspirations, will make of our liturgies what they are truly meant to be in the plan of God: a divine work and the work of the Church.

The Holy Spirit recalls the mystery of Christ

We saw above that the Catechism treats the Holy Spirit and the Church together in this section precisely because it wants to emphasize that the Spirit brings it about that the liturgy actually becomes “the common work of the Holy Spirit and the Church” (§1091). In the strongest sense of the word, the Spirit and the Church co-operate in the liturgy. The priority, of course, is in the Spirit’s action; but the Spirit acts on the Church in such a way that it can genuinely be said that liturgy is also the Church’s work, the Church’s action. Four verbs summarize the Spirit’s action: the Spirit prepares the Church to meet Christ, recalls Christ, makes present his mystery, and unites the Church to Him (§1092). Each of these dimensions is developed under separate subtitles. Previously we examined the section titled “The Holy Spirit prepares for the reception of Christ.” We turn now to the second of the four subtitled parts (§§1099-1103).

This section begins by using the technical liturgical word memorial. It says, “the liturgy is the memorial of salvation,” and then adds, “The Holy Spirit is the Church’s living memory” (§1099). This beautiful little sentence is worth unfolding. A footnote attached to it leads to John 14:26, where Jesus said, “‘But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have told you.’” Jesus’ promise still holds good. It is as fresh as ever. And one could point to the liturgy as the place where it is precisely and most fully realized.

The words of Jesus reveal that the dimension of the liturgy that is a “memorial” of the past is something far larger than the effort of a human community to keep close over time, despite the vicissitudes of history, to the memory of important past events. It is instead a divine work in which the Father sends us another gift, the Holy Spirit, to keep the gift of his Son’s own incarnate presence among human beings as fresh as in its first particular appearance in first-century Palestine. Two thousand years between us and the historical Jesus is not a gap when the Spirit is “the Church’s living memory.” The Spirit’s work is a divine work, and so is complete, total, fully accomplished.

Two dimensions of the liturgy reveal the Spirit at work in this way, and these are treated in two smaller subtitles in this section: the Word of God and Anamnesis. We all know that Scripture is read in the liturgy, but what actually is happening when that is done? Some particular member of the assembly stands up and reads, but the Spirit is operating through this action. “The Holy Spirit first recalls the meaning of the salvation event to the liturgical assembly by giving life to the Word of God…” (§1100). Two words are crucial to the claims of this sentence: meaning and life. When we hear words, they can mean many things, often too many, perhaps even contradictory. Words are risky. But the assembly is not left simply to itself and to its own wits alone for penetrating the words of Scripture correctly. The Spirit “recalls the meaning”— the divinely intended meaning “of the salvation event.” In addition to meaning, the Spirit gives life to the words. Again, words are risky. At worst, they could just be so many sounds hitting against eardrums, or they could have no more effect than the vague sensation of, “I’ve heard that before.” Instead, in the liturgy, the Spirit gives life to the words in such a way that they can be received and lived for what they truly are; namely, the very Word of God in the irreducible newness of this present moment of proclamation.

“The Holy Spirit gives a spiritual understanding of the Word of God to those who read or hear it” (§1101). The idea of spiritual understanding of the Word is introduced here as yet another concept to build upon meaning and life mentioned in the previous paragraph. Sometimes nowadays the word “spiritual” is used by religious seekers or refers to religious seekers in any number of fairly vague ways, but in Christian theology the word “spiritual” is always traceable to the Holy Spirit and to the specific work of the Holy Spirit in the divine economy. So, if here it is a question of “a spiritual understanding of the Word of God [for] those who read or hear it,” that means that the Spirit will put worshipers “into a living relationship with Christ, the Word and Image of the Father” (§1101). A living relationship with Christ is the spiritual understanding of Scripture. And it is typical that we experience and know the Spirit in the Spirit’s referring us to another, to Christ, and to Christ recognized as the Word and Image of the Father.

We do well to recall that we are examining a part of the Catechism that speaks about the Liturgy as the Work of the Holy Trinity, where the role of each member of the Trinity is distinguished and discussed. Here, in speaking about the Spirit’s role, the other Persons of the Trinity are completely implicated, as we have had occasion to see already in other formulations. This is a beautiful yielding of one Person of the Trinity toward the other. The Spirit puts us in a living relationship with the Son and helps us to know Him as Word and Image of the Father. All this is happening in the liturgy as the Word of God is read. All this is what it means to say, “The Holy Spirit recalls the mystery of Christ,” as the title of this section indicates.

“Covenant” is one way of summarizing the content of the whole of Scripture. Scripture is the story of the covenant.

But there is more. “The proclamation does not stop with a teaching; it elicits the response of faith as consent and commitment, directed at the covenant between God and his people” (§1102). So far we have seen a number of key words expressing what the Spirit delivers by means of the liturgical words and actions: meaning, life, understanding, living relationship with Christ. Now the direction shifts. All this requires a response, but the response itself is helped by the Spirit. This divine help is needed so that our particular response can be more than what we might come up with by ourselves, so that it can be bigger than the sum of the parts of the vision of a particular gathered community. That bigger response is here described as “consent and commitment directed at the covenant between God and his people.” So, Christian liturgy is more than simply some of the baptized gathered together to hear a little Scripture and think about it. The hearing of Scripture in the Spirit ought to bring us to nothing less than a consent and commitment to enter into—huge words!—the covenant between God and his people. “Covenant” is one way of summarizing the content of the whole of Scripture. Scripture is the story of the covenant. In the liturgy we do not hear this story as information about religious people of the past. Hearing it means for us to enter into that same covenant in the here and now of this particular liturgy: "It is the Holy Spirit who gives the grace of faith, strengthens it and makes it grow in the community” (§1102).

All these ideas considered so far were under the smaller subtitle “The Word of God.” The next smaller subtitle is “Anamnesis,” and this is treated in just one paragraph. Anamnesis is a technical word used to describe a fundamental dimension of all liturgy, and its introduction here is part of the learning that the Catechism wants to promote. A simple, useful description is offered: “the liturgical celebration always refers to God’s saving interventions in history” (§1103). We could say that God’s saving interventions in history are a large part of the content of liturgy. Those interventions are what many of the words refer to, whether they are the words of Scripture or of prayer; and they are also the sense and meaning of the various symbols and ritual actions. This is true of all liturgical celebrations. At this point the Catechism is speaking in general terms that are meant to apply to all the sacraments and all the other liturgies that the Church celebrates. In all of these, “the celebration ‘makes a remembrance’ of the marvelous works of God in an anamnesis which may be more or less developed” (§1103).

The center of the saving interventions of God in history is, of course, the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ; and this is the ultimate content of all anamnesis. In the liturgy, the Death and Resurrection of Christ is “remembered” in a qualitatively unique way. It is remembered by the Holy Spirit for the Church. Then there is “co-operation.” The Church willingly makes remembrance in the way that the Spirit fashions. This is not memory in the form of information from the past. It is memory that gives meaning, life, understanding, living relationship with Christ. And, “The Holy Spirit who thus awakens the memory of the Church then inspires thanksgiving and praise (doxology)” (§1103).

We have examined here five rich paragraphs grouped under the title, “The Holy Spirit recalls the mystery of Christ.” This is the second of four subtitles that treat the role of the Holy Spirit and the Church in the liturgy. The third subtitle picks up immediately from this sense of the memory of the past and brings it into the present. The first sentence of the next section connects us with this. “Christian liturgy not only recalls the events that saved us but actualizes them, makes them present” (§1104). This will be our next subject.

Celebrating the Paschal Mystery

Recalling the saving events of God in history is thus a major dimension of the liturgy. But this does not exhaust all that happens. “Christian liturgy not only recalls the events that saved us but actualizes them, makes them present” (§1104). This is followed by a sentence that makes a very useful distinction: “The Paschal Mystery of Christ is celebrated, not repeated.” With the term “Paschal Mystery” the Catechism goes to the heart of what is remembered in liturgy.

I hope that just several lines of that important paragraph cited here can throw into relief the importance of this cross reference. We read, “The Paschal mystery of Christ, by contrast, cannot remain only in the past, because by his death he destroyed death, and all that Christ is—all that he did and suffered for all men— participates in the divine eternity, and so transcends all times while being made present in them all” (§1085). This is the logic behind saying now at §1104 that, “The Paschal Mystery of Christ is celebrated, not repeated.” That the Paschal Mystery can be made present in all times is the work of the Holy Spirit and comes about through the liturgical celebration. §1104 continues, “It is the celebrations that are repeated, and in each celebration there is an outpouring of the Holy Spirit that makes the unique mystery present.”

§1105 introduces the technical liturgical term epiclesis, a term always associated with the Holy Spirit in the liturgy. It explains, “The Epiclesis (“invocation upon”) is the intercession in which the priest begs the Father to send the Holy Spirit, the Sanctifier, so that the offerings may become the body and blood of Christ and that the faithful, by receiving them, may themselves become a living offering to God.” This explanation focuses on what happens in the Eucharist, where the strongest, most forceful action of the Spirit is at work. In the present moment of the liturgy the offerings are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ. As such, the transformed offerings render present the Paschal Mystery, whose roots are in the past but in the here and now of the liturgy “transcends all times while being made present in them all.”

Further, the Paschal Mystery is rendered present not in some static way. That is impossible and would contradict the very meaning of the Mystery. Rather, it is rendered present in a way that directly effects us who celebrate. It is rendered present precisely in such a way that the faithful who receive the Body and Blood of Christ may be themselves transformed into what they receive and in this way become “a living offering to God.”

Taken seriously, these are dizzying claims. When the Father sends the Spirit onto the offerings, bread and wine are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ; and we who receive them are transformed by the same Spirit into what we receive. This “form” into which we are “trans-formed” is named here “living offering to God,” and a footnote references Romans 12:1. It is important to take note of this scriptural warrant because this verse virtually from the beginning of the Christian community’s existence has exercised enormous influence on how the eucharistic celebration is understood. Paul is taking account here of the enormous implications of life in Christ and contrasting it with his own former Jewish practice and worship.

What is possible now in Christ is a new kind of sacrifice, a new kind of worship, a new cult. Paul urges—and the reader feels his solemn wonder—“offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, your spiritual worship.” What Paul is speaking about here effectively comes about when “the faithful, by receiving [the transformed gifts] themselves become a living offering to God.”

Even if the illustration here of the word epiclesis is made in reference to the Eucharist, what is said is meant to apply more broadly. “Together with the anamnesis, the epiclesis is at the heart of each sacramental celebration.” (§1106). This is not developed further in the Catechism, but awareness of anamnesis and epiclesis in every celebration of any of the sacraments is one of the most effective ways of attending to what is happening, what is effected by the Holy Trinity, in that celebration.

In this subtitle about how the Holy Spirit makes present the mystery of Christ, the connection with the past has been clearly made. The events from the past that saved us are actualized and made present. The last paragraph of this subtitle also speaks of something more paradoxical, more unexpected. The Spirit also mysteriously causes the future to make its presence and effects felt now. “While we wait in hope he [the Holy Spirit] causes us really to anticipate the fullness of communion with the Holy Trinity” (§1107). Communion with the Holy Trinity is meant to be our definitive future, yet even now, in the liturgy, we are really anticipating that future. The Spirit is the gift of the Father given to the Church in answer to her request for precisely that. “Sent by the Father who hears the epiclesis of the Church, the Spirit gives life to those who accept him and is, even now, the ‘guarantee’ of their inheritance.”

The Catechism places the word “guarantee” in quotation marks and in a footnote refers us to Eph 1:14 and 2 Cor 1:22. St. Paul uses this word for the Holy Spirit, and the community experiences that guarantee in the liturgy. In the present here and now of what the Spirit does for us, we already enjoy the inheritance for which we are destined. In Paul’s own words: “we . . . were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit, who is the guarantee of our inheritance until we acquire possession of it, to the praise of his glory” (Eph 1:14).

The communion of the Holy Spirit (§§1108-1109)

This is the fourth and final subtitle in the section of the Catechism treating the Holy Spirit and the Church in the liturgy. The word “communion” is used to indicate the culmination of what the Spirit prepares, recalls, and makes present. “In every liturgical action the Holy Spirit is sent in order to bring us into communion with Christ and so to form his Body” (§1108). Closely associated with this is another word: “cooperation”; and with this word the Catechism comes full circle from a point introduced at the beginning of this whole development. I have had occasion more than once to take note of the Catechism’s stress that the liturgy becomes the common work of the Holy Spirit and the Church. This can be said again now at the end. “The most intimate cooperation of the Holy Spirit and the Church is achieved in the liturgy.” The Spirit is called here Spirit of communion, and the Church is called “the great sacrament of divine communion which gathers God’s scattered children together.” Gathered where and how? Communion with whom? “Communion with the Holy Trinity and fraternal communion are inseparably the fruit of the Spirit in the liturgy” (§1108).

The last paragraph of this whole section on the Spirit and the Church can serve as a succinct and moving summary of all that we have seen in our analysis of the Holy Spirit and the Church in the liturgy. “The mission of the Holy Spirit in the liturgy of the Church is to prepare the assembly to encounter Christ; to recall and manifest Christ to the faith of the assembly; to make the saving work of Christ present and active by his transforming power; and to make the gift of communion bear fruit in the Church” (§1112).

![]()

Editors' Note: This essay is an adaptation of a series of articles published in Church Life Journal from 2012-13.

Featured image: El Greco, Pentecost (ca. 1600), detail; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons