When I found out that I got a job teaching high school theology, I began to ask all of the teachers I knew what advice they had for me. I heard all kinds of things about classroom management and lesson plan preparation. However, the one piece of advice that has stayed with me came from a professor at Notre Dame.

“I’m going to be a high school theology teacher, Professor. Do you have any advice for me?”

“Jesus told his disciples, ‘You give them something to eat.’”

“Pardon?”

“Jesus told his disciples, ‘You give them something to eat.’”

“…?”

I’ve thought more about this puzzling piece of “advice” than any other. In the ninth chapter of Luke (and the sixth of Mark), Jesus goes out to a deserted place. When the people follow Him, but turn out to be hungry, the Apostles ask for Jesus to send the crowds away. Jesus says instead, “You give them something to eat” (cf. Lk 9:13 and Mk 6:37). Of course, they have no money to be able to pay for the food that it would take to feed the multitudes. Nevertheless, Jesus tells them to sit the people down and feed them. In the end, it is Jesus who performs the miracle, who blesses the food, and gives it to those gathered. Jesus asks the disciples to give the people something to eat, though, of course, there was no way for them accomplish this task on their own.

I’m not sure, but I think that this may have been what my professor was telling me. My teaching will never be my own work. Jesus will speak to the heart and enlighten the mind. Jesus will perform the miracle of education. Though, like all miracles, this one comes through simple, humble, and sinful vessels. I still have to show up. I still need to wake up before dawn each day, still need to grade papers on the weekends and go to basketball games on the weeknights. Jesus says to the teacher, “You give them something to eat.” “You give them an education.” Then he provides all that the teacher needs to accomplish that mission.

The first question to ask may be: what is the purpose of education? In this context, I’m thinking particularly of Catholic education. The ultimate answer must be salvation. It is difficult, though, to see a direct, replicable line from education to salvation. The proximate, more directly attainable goal, however, is to build character. As teachers we can help our students to be good. We can teach thoughtfulness, discipline, respectfulness, and hard work. Much lower down on the totem pole of goals is worldly success. I wouldn’t be any more proud if my former student is busted for corporate embezzlement than if he gets nabbed for purse snatching.

One cannot feed others with that which he or she does not have to give.

In order to accomplish this mission, though, there is a prerequisite for the teacher. Remember that Christ is asking his Apostles, not the crowd, to change. We cannot pretend that the formation of a good teacher is limited to his or her classroom. Simply being an effective conveyor of information is not nearly enough. The educator him or herself must be formed. To be a good teacher, the teacher must be good. In Richard Tierney, SJ’s work, Teacher and Teaching, he says that the teacher “must himself be a man of character. He must tower over his pupils in soul power. The frog can scarcely teach the young mocking-bird to sing” (7–8). Put another way, one cannot feed others with that which he or she does not have to give. Continual personal formation and conversion are essential to the teacher’s ability to form young people.

I do not want to minimize the importance of the intellectual and practical skills that are necessary to be a teacher. Knowledge of classroom management, mastery of content, and adept delivery, in short, sound pedagogy, is critically important. While essential and necessary, for Catholic education, they are fundamentally secondary. Catholic education has a larger goal that is only served by educators who are able to help their students to be good.

Christian education is never simply a transfer of facts or skills—the Pythagorean theorem or how to diagram a sentence. Education, at its most fundamental level, teaches the truth. By doing this, it teaches Christ, who is the Truth. Wherever there is truth to be found, we find Christ. In mathematics, the sciences, social studies, or language arts, Christ, who is Truth and Wisdom, is there. Christ is present in each classroom, because teaching the truth means teaching Christ. And in teaching this truth, we feed our multitudes.

Two Visionaries of Christian Pedagogy

While there have been many visionaries within the Church explaining a uniquely Christian understanding of education, two of these provide particularly valuable perspectives. St. Jean-Baptiste de la Salle (1651–1719) is the patron saint of educators. St. John Bosco (1815–1888) is the patron saint of schoolchildren. While both were founders of education orders, they have different visions of how one carries out the task of education, and they provide valuable counterpoints to each other. The reason that one is the patron of teachers and the other the patron of students becomes readily apparent through their writings and educational philosophies.

|

| St. Jean-Baptiste de la Salle; Photo: Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca; CC-BY-2.0. |

Jean-Baptiste de la Salle’s work in education began in 1679 in France, but this Lasallian model has spread to over 1000 educational institutions across the world in more than 80 countries. In his work The Conduct of Christian Schools, de la Salle laid out very specific guidelines for how his schools were to be run. De la Salle was a schoolmaster, not a friend, for these students. He demanded discipline in every aspect of the school’s life.

Care will be taken that they do not assemble in a crowd in the street before the door is opened and that they do not make noise by shouting or singing. They will not be permitted to amuse themselves by playing and running in the vicinity of the school during this time nor to disturb the neighbors in any manner whatsoever. (61)

Jean-Baptiste de la Salle desired discipline in his schools. I think about one particular student of mine who came from a broken family, got into drugs and alcohol early, but was as smart as anyone in his class. When he was talking with me about why he was making poor decisions and getting bad grades, he came to the conclusion, “No one ever showed me.” We, the adults in his life, never showed him how to work hard to get a good grade. We never showed him that studying and learning can actually be a fulfilling experience. We never showed him that making the right choice can actually bring more happiness than doing what brings pleasure for the moment. We never showed him that the discipline that de la Salle desired could actually help him in the long run.

Teenagers in particular are susceptible to conflating the feelings for a particular teacher with the feelings for the subject that the teacher teaches.

Educators (along with parents, of course, the primary teachers) have this responsibility to show our students what it means to be disciplined, steady, and faithful. It may seem, when reading de la Salle’s works, that he was asking his teachers to be distant or unfeeling. He wasn’t. He was asking his teachers to feed their students character and truth. He wanted the teachers to feed by showing.

In many of his regulations for the educators at his schools, he desired that the educators enforce discipline through their example. One of the traits that he asked new teachers to guard against was familiarity. He wrote:

To cure familiarity quickly, there is only one thing to be done: teachers in training must neither talk to the students nor allow the students to speak to them, the Supervisor being sure that these new teachers speak to their students only in cases of great necessity. They are not to speak from their place in the classroom. They are not to speak in a loud voice, and must never laugh with the students. (260)

Every aspect of the school day was prescribed down to the manner in which the boys would dip their pens in the ink and what the inkwells were to be made of. Doesn’t exactly sound like fun, but fun was certainly not his purpose. While some of these instructions are historical relics and not central to de la Salle’s message, they are emblematic of his larger concern. The children that de la Salle was educating were truly children of the street. He wanted to take these “urchins” and turn them into faithful and productive members of society and the Church. He needed to root out stubbornness and replace it with docility, pettiness with magnanimity, and ignorance with knowledge. All of this takes careful instruction and discipline. The educators teach this through their own example.

This means, of course, that the discipline that de la Salle required was not meant solely for the students. Teachers need to allow themselves to be fed by the same truth with which they feed their students. It is “through their witness and behavior” that the teachers mold their students, according to de la Salle. In his work, The Spirituality of Christian Education, he says to his teachers:

You . . . must devote yourselves to reading, prayer, to instruct yourselves thoroughly in the truths and the holy maxims you wish to teach, and to draw down on yourselves by prayer the grace of God that you need to do this work according to the Spirit and the intention of the Church, which entrusts it to you. (57)

The teacher is constantly to be a model to the students in action and belief. One thing I learned very quickly was that my students really wanted to know if I believed what I taught them. When they found out that I did, I had tremendously more credibility. Even though some of the things I had to tell them were difficult to hear, they desired to know the truth. A wise woman once told me that truth has its own gentle persuasion. De la Salle recognized this fact. But it is not simply about how we interact with our students. We are also models outside of the traditional classroom setting—interacting with colleagues, in prayer (or not), or in the daily tasks of life. The students don’t often realize how much we see of their lives from up at the front of the classroom, but the opposite is also often true. Only by being good can we help the students to desire that as well. For de la Salle, it was through their witness of faith that his teachers were to feed the students.

John Bosco provides a very different, but ultimately complimentary, model of education. Working in the mid- to late-nineteenth century in Italy provided a very different context than de la Salle’s. John Bosco’s primary concern was not discipline. His overarching desire was that “the boys should not only be loved, but realize that they are loved.” He did not want his priests and brothers to be interacting with the students as aloof professors or statue-like role models.

In his “Letter from Rome,” written to one of the members of his new order, Don Bosco lamented the state of the relationship between the leaders of the school and the students and the division and discontent which it fostered: “the superiors are seen precisely as superiors and not at all as fathers, brothers and friends.” He went on to explain that the only way to build up this trust again was by “a friendly relationship with the boys . . . Affection can’t be shown without this friendly relationship, and unless affection is seen there can be no confidence.” He made the very practical point that it is this which will allow the educators to be better with the students:

This love enables superiors to bear with weariness, annoyance, ingratitude, or the troubles, failings and neglect of the boys.

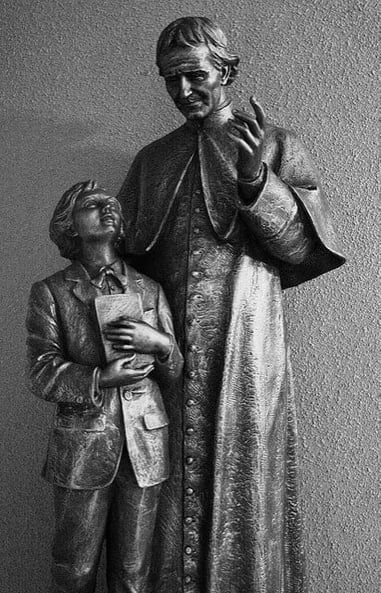

|

| St. John Bosco; Photo: Lawrence Lew, OP; CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0. |

That teachers need to love their students is true, but is an idea that has become almost trite. What does he really mean by this? Bosco wanted us to realize that our students are not simply names on a roster, a blur of faces as the years roll by. Their education cannot be formulaic. It is all too easy to give into the “weariness, annoyance, ingratitude, troubles, failings, and neglect” of our students. By truly loving them, the educator guards against this temptation.

In a paper about her own life story, one girl wrote the following:

Before I knew it I had the reputation of a slut. Boys would come to me if they wanted action and girls stayed away from me because they weren’t into that kind of stuff. This made my depression even worse. To cope with everything I was dealing with I started cutting myself. I told myself I didn’t care what other people thought of me, but truthfully I did care and it hurt me so much to go to school every day and have people calling me a slut, and knowing what they said was true.

This is just one example of the dozens of stories I hear from the young people I teach. How can I respond to this with anything other than the love and compassion that Don Bosco called for?

By seeing the student as a mystery, we can respond to them better. We can show them the love of God better. We can be less impatient with their failings.

In Mark 10 we read a story of Christ as a teacher. He encounters a rich young man who asks Jesus to teach him how he might inherit eternal life. Part of the way through the story it says, “Jesus looked at him and loved him.” Jesus is helping us to realize that teaching also means truly looking at a student and loving him or her. Don Bosco recognized this reality as well. They are both teaching us to see each student sitting in front of us as an unfathomable mystery. Every teacher needs to recognize the depth and profundity of that mystery if he or she is able to truly teach students well. This is part of acknowledging the humanity of the young people who sit in front of us. Teenagers in particular are susceptible to conflating the feelings for a particular teacher with the feelings for the subject that the teacher teaches. If he hates his math teacher, very often he will end up hating math. If she loves and respects her history teacher, she will end up loving history. (In this the theology teacher has a special responsibility because he or she represents not only an academic subject but also faith and God Himself.)

Each student carries an inner life, of which I can only ever be witness to a tiny fraction. Inevitably, the moment that I think I know a student is the moment that I’m told of his abuse or her struggle with an eating disorder. By seeing the student as a mystery, we can respond to them better. We can show them the love of God better. We can be less impatient with their failings. Ultimately, we can be better ourselves, and through that witness, help them to be better as well. In all of this, in our love and compassion, we feed our students.

Just as de la Salle was right in his call for structure and discipline, Don Bosco was right when he stated that our students need to be loved and know that they are loved. We need to hold onto both of these visions. One of these will probably come more naturally than the other to a given teacher, but neither can be discounted. When Christ asks us to give our students something to eat, we must give the food of our witness and the food of our love, our discipline and our companionship, our steadiness and our compassion.

Christ in the Classroom

Looking across my classroom can sometimes be a disheartening experience. The wall decorations, once bright and square, are looking decidedly droopy. The white boards are dirty, and the bookshelves are disheveled. Not only that, but Ben is gazing blankly out of the window again. Shannon, whose thumb clearly needs its daily workout, will not stop clicking that pen. Tim raises his hand, for a change, during the most important part of the lecture, only to ask if he can go to the bathroom. Adam is apparently working on his stand-up routine for his neighbors. And if Lisa rolls her eyes one more time, or sighs that loud sigh of hers, I might just walk out of the building right now, get in my car, and not look back. I think that most teachers have had an experience like this, and it’s in these moments that we learn whether or not we are good teachers.

Can I be patient when I want to lose my temper? Can I be kind when the students are not? Can I be generous, loving, joyful, and compassionate? Can I continue to be disciplined myself? Can I continue to recognize that these beautifully imperfect students are still infinite mysteries and beloved by God, even when they are less than beloved by me? Can I continue to respond to God’s call to feed these students even when I feel that I am utterly unequal to the task?

There is a particular passage from the Jewish Talmud, written on the wall in the classroom of a Jewish colleague, which describes well the task of a teacher. The Rabbis tell the students who study the Torah, "You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it"(Pirke Avot 2:21). The work of the teacher is never finished. There will always be more papers to be graded, more lesson plans to be written, and more students’ stories to hear. There is a relentlessness to teaching that not even a summer break can alleviate. It is tempting to give in to a quiet despair, convinced of the fact that we will never finish this task. And, in fact, we won’t. Still, we are not free to desist. Christ told his penniless Apostles, “You give them something to eat.” Every day we will show up with energy, love, and lesson plans, confident that even though we’re being asked to do the educating, it’s Christ who does the feeding.

![]()

Editors’ Note: This essay originally appeared in Church Life: A Journal for the New Evangelization, volume 2, issue 2.

Featured Image: Alexander Andreyevish Ivanov; Multiplication of the Loaves (19th c); courtesy Wikimedia Commons.