Today, September 30, the Church celebrates the feast of St. Jerome (ca. 345/7–420), one of the four great Latin doctors of the Church, along with Sts. Ambrose, Augustine, and Gregory the Great. He is primarily known for translating the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures (both Old and New Testaments) into Latin. His translation, known as the Vulgate, was adopted as the official Latin translation of the Bible.

Yet St. Jerome’s scriptural scholarship was not simply relegated to translating, though that achievement alone was certainly monumental enough to earn him an honored place in the Church’s history. In addition to his translation, St. Jerome also penned commentaries on various books of the Bible, including the prophet Isaiah and the gospel according to Matthew. For Jerome, it wasn’t enough to render the scriptural texts accessible from a purely linguistic standpoint; he also sought to help others encounter the Word of God more deeply by sharing the fruits of his contemplation, gained over a lifetime of poring over, meditating upon, and praying with the Scriptures.

Jerome took to heart the mystery that the Scriptures are not dead words, and his lifelong contemplation testified that “the Word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Hebrews 4:12). In St. Jerome, we see a saint who believed wholeheartedly that “in the sacred books, the Father who is in heaven comes lovingly to meet his children, and talks with them” (Dei Verbum, §21). Indeed, he was so deeply committed to this mysterious life present in the Word of God that he wrote in his commentary on the prophet Isaiah, “Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ” (see Dei Verbum, §25 and CCC, §133).

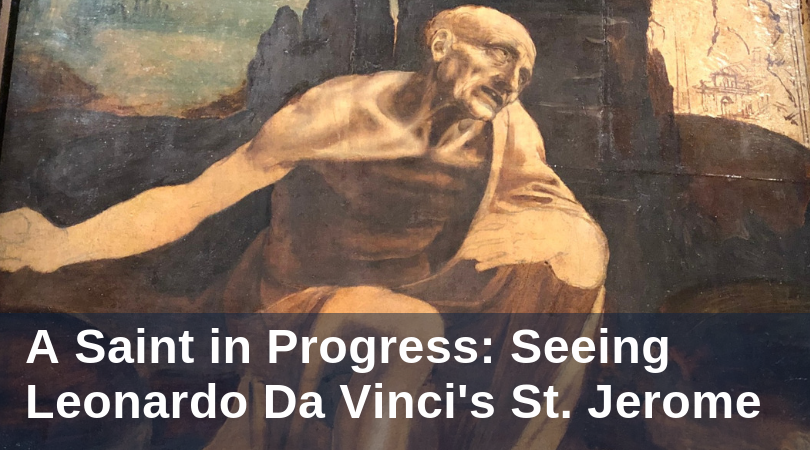

For all his words on the Scriptures, it is perhaps more immediate to encounter Jerome as he is depicted in art. Currently on display at the 5th Avenue Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519) entitled Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness, on special loan from the Vatican Museum until October 6, 2019, in honor of the 500th anniversary of Da Vinci’s death. On a recent trip to the Big Apple, I had an opportunity to visit the Met and view this extraordinary work, and discovered in it not only an incredible glimpse into Da Vinci’s artistic process and a vivid visual commentary on St. Jerome, but also a profound analogy to the kind of relationship with Scripture that all Christians ought to cultivate.

For all his words on the Scriptures, it is perhaps more immediate to encounter Jerome as he is depicted in art. Currently on display at the 5th Avenue Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519) entitled Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness, on special loan from the Vatican Museum until October 6, 2019, in honor of the 500th anniversary of Da Vinci’s death. On a recent trip to the Big Apple, I had an opportunity to visit the Met and view this extraordinary work, and discovered in it not only an incredible glimpse into Da Vinci’s artistic process and a vivid visual commentary on St. Jerome, but also a profound analogy to the kind of relationship with Scripture that all Christians ought to cultivate.

A Glimpse into Artistic Genius

To begin with, the painting is unfinished. Da Vinci began it around 1483 and revisited it several times throughout the remainder of his career. There are distinct stages of completion represented throughout the composition: to the right of Jerome’s head is the sketch of a cave with the slightest indications of a crucifix that draws his gaze, and at his feet lies an open-mouthed lion that seems almost ready to stand up. Much of Jerome’s body itself is also unfinished; his hands, feet, and the bottom of his cloak barely sketched in place. His torso and face, however, offer a different story. Here, Da Vinci—exacting in his desire to depict the naturalism of the human body—has painstakingly depicted a moment of intense anguish, or ecstasy, or both. The shoulders are hunched forward, the muscles taut, the bones visible beneath the skin. With this glimpse into his artistic process, Da Vinci also gives viewers a glimpse into the soul of St. Jerome.

An Ascetic Hermit

Da Vinci shows St. Jerome during the time he spent as a hermit in the desert. The sparseness of the saint’s environment, clothing, even his advanced age and lack of teeth indicate that all worldly trappings have been forsaken for the sake of knowing “nothing . . . except Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2). The saint swings his left arm back, holding a stone in his hand, perhaps preparing to strike his breast in a penitential gesture, as he cranes his gaunt, almost skeletal face to fix his eyes on Christ crucified, whom he has encountered in the Scriptures.

A Scriptural Analogy

Da Vinci’s unfinished painting of the translator of Scripture reminds the Christian viewer that one’s relationship with Scripture can never be ‘finished.’ There will always be more to encounter in pondering the Word of God, for it is the living Word of God; it is God himself whom we encounter in Scriptures. St. Jerome himself is a remarkable example of this, having dedicated his life not only to making Scripture more accessible to others, but to contemplating their richness with single-hearted focus, in order to encounter the One who dwells therein, Jesus Christ, the Word of God made flesh.

Images courtesy of the author.