Editorial Note: This excerpt is taken from an essay entitled "Mental Illness in Light of the Theophany Icon" by Joel Looper, originally published at Church Life Journal on August 5, 2019.

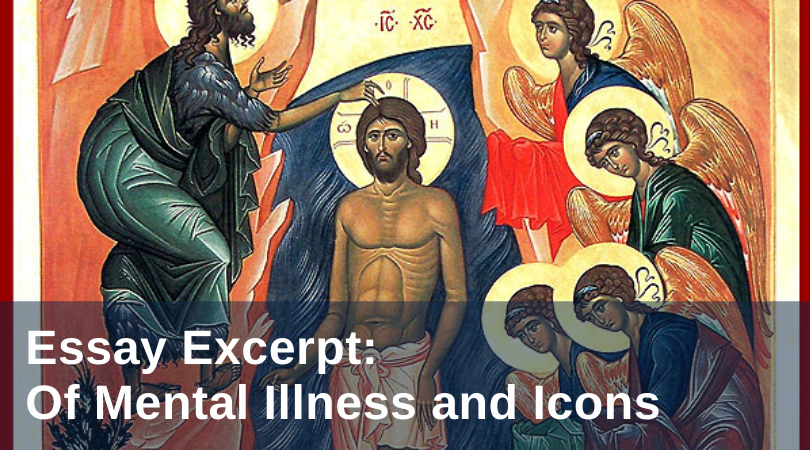

An icon hangs inside the door of my study, positioned above the light switch so that my eye hits upon it whenever I leave the room. The writer of the icon (for icons are said to be written not painted) took as his subject the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River . . .

A former roommate gave me this icon one day without explanation. For the purposes of this essay I will call this roommate Lawrence. Lawrence is a probably a schizophrenic, or perhaps bipolar, or both. I do not know if he has ever received a definitive diagnosis. He also had a drug problem, which is very common among those experiencing mental illness. Lawrence nearly died at least twice during the time we lived together. He lost his job, lost a relationship, and I witnessed him in physical altercations with police officers on two different occasions. He spent a few months in a psychiatric hospital to no avail. He alienated nearly everyone who tried to help him. He barged into the classroom of his favorite college professor, one of the only non-family members who stuck with him as he degenerated, and terrified his students.

. . . . One day, probably two months after he had given me the icon, I got a call that Lawrence had been admitted to the psychiatric unit at the local hospital.

The rooms in the psych unit were white, which, of course, is what I had expected. A doctor led me in to a large, spare waiting room. The wall adjacent to the hallway was glass; there was nowhere for anyone to hide. After a few minutes they brought Lawrence in. He was calm and dressed in clean clothes, but he looked as if he had not slept in days.

“Lawrence . . . ,” I said, “Are you doing okay?”

Lawrence responded with jokes: bad jokes, incomprehensible jokes, dirty jokes. He grew happy, almost giddy. He was stable, which was good. But he was most certainly not the Lawrence I had known before.

I realized as we talked that night that it was not just Lawrence’s body that was broken, but his very self. There is no cure for schizophrenia. Short of a miracle, that self will remain more or less as it is, shattered, not merely unable to choose the good, but often unable to recognize it.

. . .

To borrow a line from George Herbert, Lawrence was not just “a brittle, crazy glass,” but a mirror destroyed, one that no longer seemed to reflect the reign of Christ at all. If Lawrence’s life today resembles what it did several years ago, his hope in Christ, when it is there at all, shows up in manic flights of the imagination—frightening, disconnected thoughts about the beginning or end of the world.

What is the Church to say about those like Lawrence? What are we to tell ourselves about the sum of his life? . . .

Maybe the church needs to accept again the category of the holy fool as depicted in Laurus, Eugene Vodolazkin's novel of late Medieval Russia. Perhaps we should tell ourselves that there is more to Lawrence’s life than we know, more that God will do through him than we could guess, and begin, however falteringly, to expect this “more.”

Expecting more sounds fine in theory, but when your friend or family member’s unrelenting paranoia or impulsive, dangerous behavior turn life into a tangle of frayed nerves and repeated iterations of the same grueling test of wills—then “more” is too much. The traumas experienced by families such as Lawrence’s make our question about the sum of the life of the severely mentally ill both painful and unavoidable.

If this “more” arises from a this-worldly faith—a determined, even pious optimism held in the teeth of the facts or a dogged conviction of hidden capacities or wisdom possessed by the ill friend or family member—the day will come when all optimism and conviction have corroded, leaving behind a patina of bitterness. “What good have we done him?” friends and family will ask, and find they have no answer.

The only decisive answer to the problem of severe mental illness is, I have come to believe, not an answer exactly. Instead, it is what the New Testament writers meant when they used the word “hope.” Of course, the first Christians’ hope was also a future hope, and they too lived with the conviction of the present meaningfulness of their lives. Yet, they did so because of what they believed God had done in Jesus Christ, not because of their beliefs about the severely mentally ill or anyone else’s particular sufferings.

Visit Church Life Journal to read the full essay:

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons; public domain.