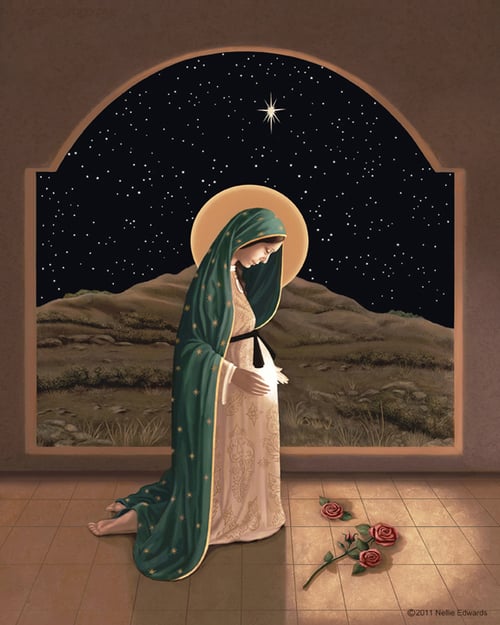

An unconventional portrayal of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Nellie Edwards’ “Mother of Life” immediately draws the viewer’s gaze to Mary’s face, an expression of stoic serenity. Her glowing visage imparts an inexplicable restfulness; she articulates no rational explanation for her peace, yet her image communicates, in fact imparts, a definitive grace. Eventually, the slope of her mantle and bowed head guide us to the image’s center: the Light of Christ in her womb. We now discover the source of her firm tranquility to be the Christ-Child, whose radiance is almost too bright for our eyes to hold.

As we avert our gaze, we sense that Mary has steadily maintained her look of adoration for a while. The unique gift of her Immaculate Conception—her preemptive redemption in her own mother’s womb—has prevented her from suffering the same sensitivity to light that afflicts all sinners (see Acts 9:18). Having totally submitted to God, she is able to behold, and hold, Love Incarnate with unwavering faith. Christ is her vision, the source and object of her love. “Mother of Life” makes it clear that Mary’s holiness is pure grace bestowed by God. It is a gift that only glorifies her because it first and foremost glorifies Christ the Head, whose radiance in her womb outshines her halo. Christ has so humbled himself that he has submitted to the darkness of the womb and the world alike. What is revelatory, though subtle, is that because he is the primary light source of the image, even the shadows must fall in reference to him. Thus, Mary bears Christ’s light forth into the world so that he might overcome the darkness, that we might “regain [our] sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit” (Acts 9:17).

As we avert our gaze, we sense that Mary has steadily maintained her look of adoration for a while. The unique gift of her Immaculate Conception—her preemptive redemption in her own mother’s womb—has prevented her from suffering the same sensitivity to light that afflicts all sinners (see Acts 9:18). Having totally submitted to God, she is able to behold, and hold, Love Incarnate with unwavering faith. Christ is her vision, the source and object of her love. “Mother of Life” makes it clear that Mary’s holiness is pure grace bestowed by God. It is a gift that only glorifies her because it first and foremost glorifies Christ the Head, whose radiance in her womb outshines her halo. Christ has so humbled himself that he has submitted to the darkness of the womb and the world alike. What is revelatory, though subtle, is that because he is the primary light source of the image, even the shadows must fall in reference to him. Thus, Mary bears Christ’s light forth into the world so that he might overcome the darkness, that we might “regain [our] sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit” (Acts 9:17).

Magnifying the Lord, Mary’s barefoot humanity invites us to imitate her and thereby become one with Christ. As Timothy O’Malley writes in Divine Blessing: Liturgical Formation in the RCIA, “The more we enter into the human condition by giving our will over to God, just like the Blessed Virgin Mary, the more that we become divine” (37–38). Mary’s embodied fiat gives her leverage to heal the cultural malaises that obstruct our culture from right worship. Her pregnant figure stands as a radical alternative to the self-appointed fitness gurus and positivity masters of our age. Separating their lives from faith, they try to strengthen the self through the self, claiming that the answer is YOU; attaining the good life is simply a matter of harnessing your inner strength and positive energy. Eat these pureed superfoods and flex for Instagram and you can’t fall. But this approach inevitably falls short because human personhood is not stable in itself. In the desperate effort to stabilize upon a sandy foundation, the person will become enclosed and finicky. In contrast, Mary exemplifies ultimate openness, allowing herself to be so interrupted that she is transformed. She lays her life down for the sake of her Son, and her sacrifice allows her to participate in life so abundant she cannot possess it but must bear it forth to the world.

We are invited to this same dynamic of monstrancing Christ. But in order to enter this relationship, we must first learn to imitate Mary’s constant fiat. Just imagine; had Mary ascribed to such selfish preoccupations, had she had a hang-up over postpartum stretch-marks, she would have cut herself off from new, eternal life. She would have obstructed the Incarnation.

Like the “Mother of Life,” we have to renounce cultural self-obsession and be willing to exchange our false ideals of human power and prettiness for humility and the beauty of sacrifice. Then we, too, can bear and be the light of Christ for the life of the world.

Featured image: "Mother of Life" by Nellie Edwards, www.PaintedFaith.net. Used with permission of the artist.