A Catholic school becomes liturgical insofar as it understands learning as necessitating both wonder and desire. The school must be a contemplative space rather than imitating the frenetic quality of modern life.

The liturgical quality of the school is also evident in its commitment to forming the memory of students.

In education, cultivating the student’s memory is generally considered passé. Since students have access to endless information through the Internet, they do not need to remember facts, dates, formulas, and the precise details of texts. The school no longer needs to attend to passing on this information but instead should focus on the critical thinking skills required to assess, organize, and judge an endless supply of data.

The problem with this development is that it relies on a reductive account of memory. Memory is not exclusively a storage system for the recollection of information. Rather, memory is linked to imagination.

What do I mean? The imagination is not a fanciful faculty of the mind that human beings outgrow after childhood. The imagination is our capacity to develop images, ideas, and thoughts that are not immediately sensed.

I grew up in East Tennessee. In the summer, East Tennessee possesses a certain sweet smell. When I am visiting home in the summer, this smell brings to my mind aspects of my past. I “remember” weeks spent at summer camps, late nights at parks with friends. As my sense of smell is activated, I call to mind events that are not immediately present to my senses. What is called to mind are images of my past.

Notice the link between memory and imagination. The school has a vocation to cultivate the memory for the sake of the imagination. We introduce content to students not so that they may recall it for an exam. A cultivated memory initiated into the dramas of Shakespeare, the theory of the development of the universe, and the history of art changes the way that we perceive the world.

At the heart of a Catholic education is recognizing a world given to us as a meaningful gift. The world does not consist of raw data or meaningless facts. There is a logos, an order to the world. We must be taught to see this meaning—to recognize there is more to see in everything than what is given to our senses.

This reveals the liturgical nature of memory in the Catholic school. Bread and wine, water and oil are not just raw matter. Even at the natural level, bread means more than just a functional thing to eat. Poets and artists have often captured this “more.” Initiated into their work, we no longer perceive bread in the same way. Likewise, for the Catholic, bread is ordered (at least eventually) to be consecrated as the Body and Blood of Christ. Everything in existence is full of this “more.”

A memory-less education is functionally atheistic. It is fragmentary, presuming that the world is not a unity worth beholding. It reduces the human person to function. We are project managers and technicians.

But as we learned in the last column, we are made to behold and to wonder. The more our memory is cultivated within the school, the more that we can gaze at existence as a gift worth beholding. We can see in every aspect of human life, a gift that is to be offered back to God.

This seeing takes time. It requires the cultivation of a liturgical understanding, one that we will take up in the next column in this series.

Like what you read? Submit your email below to have our newest blogs delivered directly to your inbox each week.

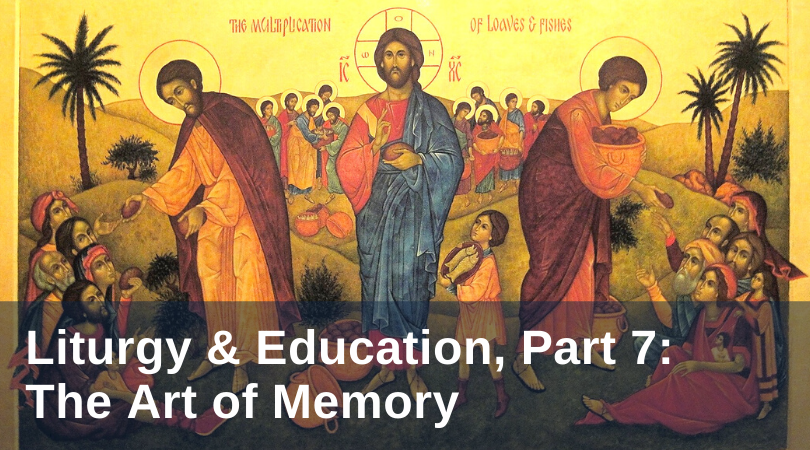

Featured image: New Skete, Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes by Sr. Patricia Reid, RSCJ; courtesy of Jim Forest via flickr; CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0.