Elijah was having a good day, until he wasn’t. He had just defeated hundreds of false prophets on his own, then brought rain down upon the drought-stricken Israel, all in the sight of the king who had been seeking his downfall. The Israelites flocked to Elijah’s God, leaving behind their divided allegiance to other deities. It was a good day––until Jezebel heard what Elijah had done.

“Thus and more may the gods do if by this time tomorrow I have not made you like one of them” (1 Kings 19:2, JPS) she cried. “Them”, of course, meant the false prophets Elijah had just slain. This was a death warrant, signed by the queen, who held the whole country under her power.

Elijah retreated. From Mount Carmel (where he had defeated the false prophets), he hastened south to Beer-sheba––a journey of four or five days by foot. He walked another day into the surrounding wilderness. There, in isolation, he collapsed in despair, pleading for the Lord to take his life. But an angel came to him, provided him with bread and water not once but twice, and sent him on his way, deeper into the desert.

Elijah walked for forty days and forty nights, until he arrived at Mount Horeb (aka, Sinai). His journey had now taken him from the site of great activity, bold words, and resounding strength on Mount Carmel, to this other mountain. And here, he sees flashes of even greater power––hurricane, earthquake, fire––which all lack what he needs: for in them, “the Lord was not.”

Instead, the Lord rests in silence.

Into the silence Elijah steps to meet the Lord. Elijah makes his confession. He had retreated from the site of his greatest victory because the powers of corruption were stronger than his impact. He retreated from the places of activity, the palaces of power, and the cities filled with people, felling into the desert. Then he kept going. He walked all the way back to where the Lord met Moses generations earlier; he walked to seek shelter in the Lord’s presence, preferring death to the alternative.

And what does the Lord say to this beleaguered prophet who came all this way? “Go back” (1 Kings 19:15).

Does that mean the retreat is over? No––it means it has just begun.

The deeper part of any mission the Lord gives is resting in his silence. Elijah returns to confront and restore all that is amiss, in obedience to the Lord’s word. But the way back is not the same as the way he came, because he now carries with him the Lord’s silent presence. Into so much noise the silence of the Lord enters through the obedience of his prophet.

Elijah, who twice cried to the Lord that “I alone am left” (1 Kings 19:10, 14), has discovered how wrong he was. The Lord did not respond to his loneliness with an explanation, but rather with his holy presence. The loneliness of the prophet became a place of communion once he let the Lord surround him in silence.

“For God has a secret language, in many people he addresses the heart, and it is a mighty murmur in the great silence of the heart when he says: ‘I am your salvation.’” (Robert Cardinal Sarah, The Power of Silence: Against the Dictatorship of Noise, 59)

Elijah’s retreat from the noise let him hear what was always there: the Lord’s abiding presence. Perhaps his head and his heart had been filled with the din of his own mighty deeds, his own expectations, the chatter and opinions of the people, and the proclamations of the tyrant. Amid that rancorous swirl, he preferred death because he was alone. The noise was not just outside of him, but inside of him. He walked and walked and walked to get away from it all. He was given sustenance for that journey. And when he was truly alone, he was not alone, because the Lord was with him.

The desert is monotheistic. In the desert it is either God, or nothing. There is nothing else to sustain life, no spectacles left to distract, no other voices to hear. It is the place of waiting to hear the one who rests in silence.

Even the ascetical practices done in the midst of the world depend on the deeper movement of the Lord’s silence. Fasting depends on the food not consumed; almsgiving depends on the alms not hoarded; prayer depends on the longings not suppressed. And yet whence come this food, these alms, these longings? They are sustained as we are sustained without our knowing. The God of Horeb is the God of Carmel, because the constancy of his presence rests within all his mighty works. His works and ours rest on his presence––not the other way around.

And so the deeper part of every Lent is a retreat from noise into silence—the silence that endures. Staying in the noise leads to despair. Leaving the noise is a start. Traveling farther than expected is necessary to hear the voice of the one who is with you always. Rediscovering him is rediscovering yourself as never alone. And when you find that, he will say: “Go back.”

Like what you read? Submit your email below to have our newest blogs delivered directly to your inbox each week.

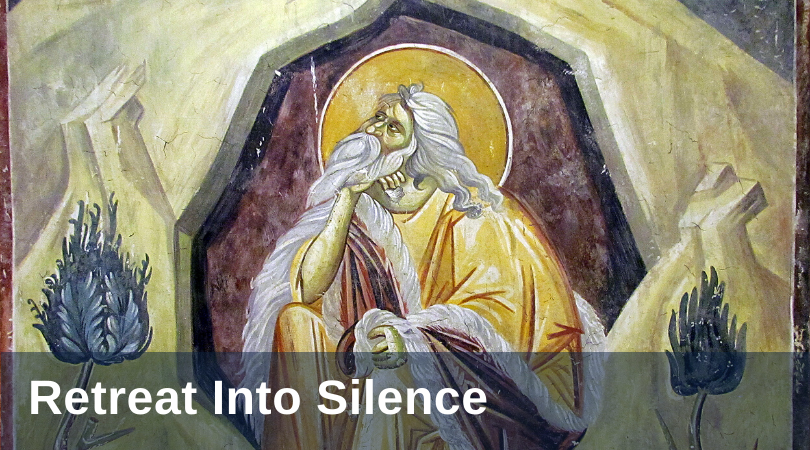

Featured Image: Elijah the Prophet; courtesy of Gmihail via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0 Serbia.