St. Peter Claver (1580–1654), whose memorial we celebrate today, offers a timely witness as our nation reckons anew with the enduring scourge of racism. The Catholic Church venerates St. Peter Claver as the patron saint of African Americans and slaves, but Claver himself was neither. Truer to his own biography, what might we learn from Claver, the pioneering patron of white anti-racism?[1]

Born in Spain to a middle-class agrarian family, Claver traveled to Cartegena, Columbia as a Jesuit missionary, where he witnessed firsthand the horrors of the slave trade. Claver began with little more than a clear sense of purpose, regarding himself as “the slave of the Negroes forever.” Sensitive to the trauma that the women and men he spoke with had suffered, Claver resolved: “We must speak to them with our hands before we try to speak to them with our lips.”[2]

When Claver did speak, he shared what was most precious to him, catechizing and baptizing an estimated 300,000 people. He also listened, hearing up to 5,000 confessions a year. Without instrumentalizing the sacraments, Claver hoped that white Christians would recognize the innate dignity of their newly baptized brothers and sisters of color. Understanding that injustice harms both victim and perpetrator, Claver implored slave traders and owners for mercy—for the sake of those they enslaved, as well as their own.

What can Christians today learn from Claver as we continue to reckon with the sin of racism?

Claver's example shows that white Christians must approach the work of racial justice first with humility. We—speaking as and principally to my fellow white Christians—need to acknowledge that our perspective on race is often distorted in ways we may not perceive.

Reading can be a kind of listening, as women and men of color narrate their experiences and challenge dominant frames of reference. Consider picking up Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Anti-Racist or Michael Eric Dyson’s Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America. Before we rush to defend ourselves against the claims such texts make, like Claver, we should ask what in another person’s experiences might contribute to deep-seated feelings of distrust, fear, or resentment.

Claver embodied the Christian virtue of solidarity, matching words with deeds. If you’re wondering how to take action, search “St. Peter Claver” online to see if any organizations in your local community are continuing aspects of his ministry. In my town of South Bend, for instance, the St. Peter Claver Catholic Worker is currently leading a local effort to re-house individuals—including many people of color—who had been previously living in a tent encampment during the pandemic.

Claver spent his final years bedridden due to illness, and his ‘caregiver’ was grossly negligent. Devoid of any sense of self-righteousness, Claver simply regarded this treatment as reparation for his own sins. St. Peter Claver invites us to examine our own participation—conscious or unconscious, active or passive—in a culture marked by ongoing racism. His zeal for sharing the Gospel reveals the surest antidote to well-intentioned, condescending white altruism, or the ‘white savior complex’: keeping our eyes clearly fixed on the true Savior, who calls us no longer slaves but friends (see John 15:15), and who commands that we do the same in love for our fellow sisters and brothers.

[1] Not to be confused with an "anti-white racist" (racism directed at whites), a white anti-racist is a white person committed to the work of dismantling and repairing the effects of racism, which the United States Bishops have defined clearly as a sin.

[2] The Knights of St. Peter Claver, the largest lay organization of Catholic African-Americans, provide an excellent short account of their namesake’s life here which served as the primary source for quotations in this piece.

Like what you read? Submit your email below to have our newest blogs delivered directly to your inbox each week.

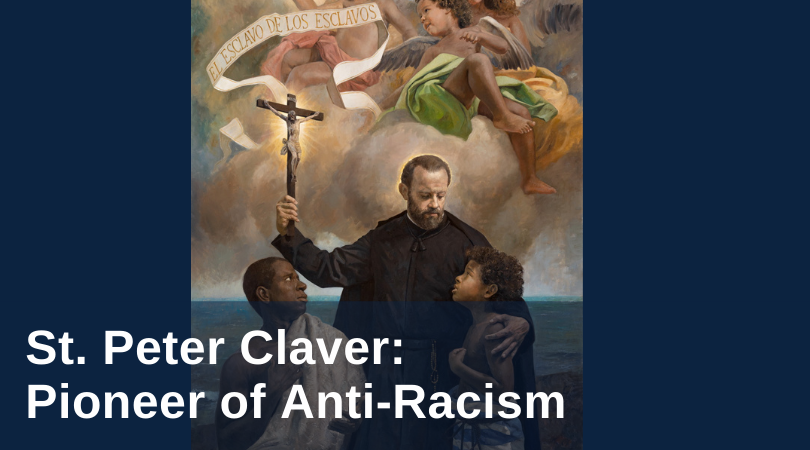

Featured image: Raúl Berzosa, San Pedro Claver (2019), detail; used with permission of the artist.